From the Archives: Editor of incendiary Charlie Hebdo magazine wants everyone to calm down

- Share via

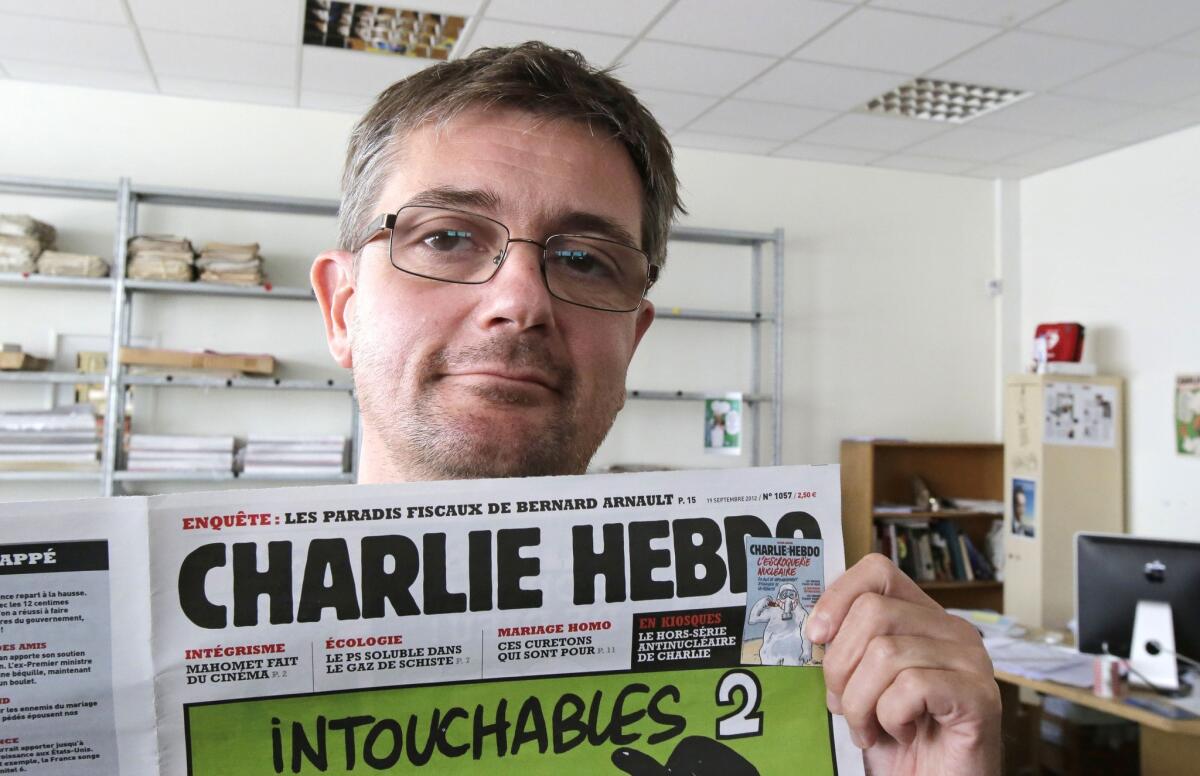

Reporting from Paris — Stephane Charbonnier, known as Charb, sits calmly behind a desk in a large, messy office with no sign outside indicating the name of his publication. True, there is a riot police car stationed in the street, but basically, he says, he doesn’t see what all the fuss is about.

“It just so happens I’m more likely to get run over by a bicycle in Paris than get assassinated,” says Charb, the soft-spoken editor of Charlie Hebdo, a left-leaning French satirical weekly, which since 2006 has been sued, threatened and firebombed for its sporadic publication of cartoons mocking the Muslim prophet Muhammad.

![]()

None of this deters Charb, who in January published a special comic book edition, “The Life of Muhammad.”

The potential consequences of printing outrageous and sexually explicit drawings involving Islam’s revered prophet just don’t seem like a big deal to the 45-year-old cartoonist, who says he started drawing because it was a way for a shy child to express himself.

The threats from Islamic extremists “come from a very small minority that doesn’t necessarily have the means to act,” he says. “If one person is injured or killed, it doesn’t mean all of France will be put on its knees.

“It’s not Islam attacking France, it’s one person attacking another person, that’s all.”

But what if you’re that person?

“Yeah, that’s rather bothersome,” admits Charb, adding that it would be harder to do the job, which he took in 2009, if he had a family to worry about.

With enough mockery of Islamic extremists and Islam (along with other religions), Charb says, he hopes the public will get so used to the drawings that little or no violence will result, or that Islam will be “trivialized” like any other religion. He says that’s already happening now.

“So let’s talk about Islam the way we talk about everything else,” he says, peering through thick glasses that enlarge his eyes almost to the exaggerated size of his bug-eyed cartoon characters, which he says he resembles.

Sumeja Rahmani, spokeswoman for the Collective Against Islamophobia in France, says that to many French Muslims, Charlie Hebdo’s content is seen as a form of hate speech in a country already struggling with integrating large swaths of its Muslim minorities, who suffer from discrimination in the workplace and elsewhere.

“Socially speaking, France is in a bad state,” Rahmani said. “What are these cartoons worth other than ridiculing Muslims more and devaluing them, insulting and offending them?

“It doesn’t make Muslims laugh, and I mean Muslims as a whole, not just extremists.”

Charlie Hebdo may be the only French media publication to have said it chooses page one stories it hopes nobody will notice. Of course, that’s not exactly true.

Some of the controversial issues featuring Muhammad caricatures have included drawings of violence, sex and nudity, often in the style of a child’s sketch — material clearly intended to attract attention and controversy.

A 2011 issue “edited” by the Muslim prophet showed a long-nosed, bearded and turbaned Muhammad warning on the cover, “100 lashes if you don’t die laughing.”

The issue then illustrated the “advantages” of so-called watered-down sharia, or Islamic law. Examples included a bearded man in a skullcap promoting “less visible polygamy” by way of marrying three burka-clad dwarfs.

A style section shows women getting their nails done on severed hands. The edition on the life of Muhammad doesn’t focus on Islamic extremism; instead it spoofs him with illustrations related to original Islamic texts about his life.

Nobody has tried to hurt Charb or bomb or even sue the publication since that edition.

Muslim leaders in France and abroad called for calm, saying citizens who wanted to protest should take legal action.

“They’re no longer calling on Arab and Muslim people to go protest in the street and protest in front of embassies; it’s simply to be indignant and use legal recourse, which is enormous progress,” Charb says.

“The message is: There’s no taboo subject in France,” he adds, noting that the topic of sex was taboo in the 1960s until publications like Charlie Hebdo, the latest incarnation of which began two decades ago, addressed it in full anatomical detail. They “continued to talk about sex, to laugh about it, and in the end it has meant sex is no longer a taboo subject.”

Dominique Avon, a comparative religion and contemporary history professor at France’s University of Maine, says reaction to illustrations of Muhammad has indeed calmed, relatively speaking, in recent years. He says the phenomenon coincides with small signs of a certain “trivialization” of Islam within Arab-Muslim societies, and indications of increasing minority secular movements.

More criticism of and disagreement between religious Islamic leaders “counts a lot more, in my opinion, than a few drawings,” he said.

Rahmani, like other critics, said the Muhammad cartoons were simply an easy way for Charlie Hebdo to increase its sales. The weekly has no ads and says it is breaking even with an average of roughly 45,000 copies sold per issue.

In 2006, Muslim groups sued the weekly for “publicly abusing a group of people because of their religion,” after it reprinted Danish cartoons of Muhammad. Judges ruled in favor of the publication, noting that the cartoons were not commenting on the entire religion of Islam.

“I think French citizens have this imaginary idea of their fellow Muslim citizens,” Rahmani said. “It becomes Islamophobic when it creates a feeling of hatred, regarding Muslims, and that is what these caricatures bring.”

Charb is quick to answer: “If a small group of terrorists, however small it is, starts to dictate its law to newspapers in France or elsewhere, that would really be a shame.”

Besides, he says, he and his colleagues just can’t help themselves. “It’s not exactly our drawings that have power, it’s our stubbornness — a stubbornness to continue doing what we feel like doing, through drawing.... It comes from the fact that I have nothing else.

“The only thing we have is our freedom of speech,” Charb says. “If we give up on that, we’d need to change fields. Do other things.”

Lauter is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.