Betty Ford dies at 93; former first lady

- Share via

Former First Lady Betty Ford, who captivated the nation with her unabashed candor and forthright discussion of her personal battles with breast cancer, prescription drug addiction and alcoholism, has died. She was 93.

Ford died Friday at the Eisenhower Medical Center in Rancho Mirage, according to Barbara Lewandrowski, a family representative. The cause was not given.

As wife of Gerald R. Ford, the 38th president of the United States and the only person to hold that office without first being elected vice president or president, she spent a brief, yet remarkable time as the nation’s first lady. But after he left office and even after his death in 2006 at 93, she had considerable influence as founder of the widely emulated Betty Ford Center in Rancho Mirage for the treatment of chemical dependencies.

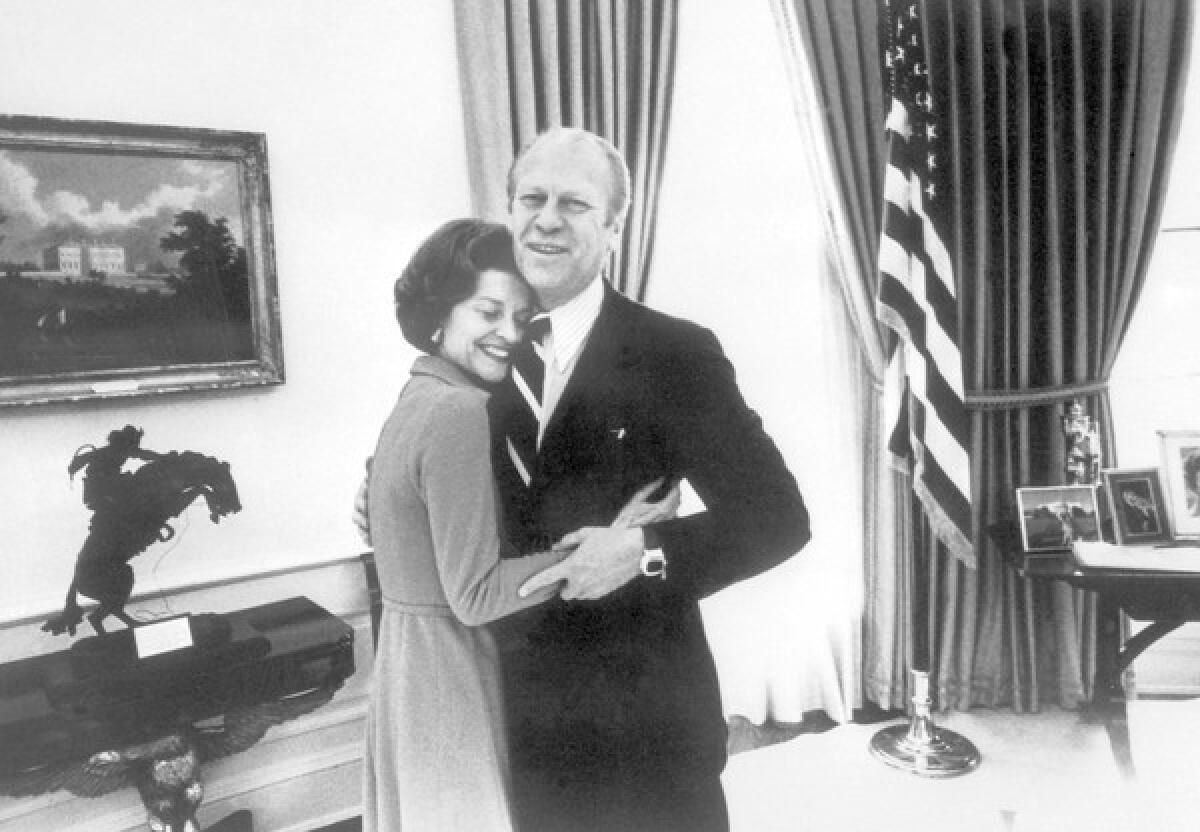

Photos: Life of former First Lady Betty Ford

“Throughout her long and active life, Elizabeth Anne Ford distinguished herself through her courage and compassion,” President Obama said Friday in a statement. “As our nation’s First Lady, she was a powerful advocate for women’s health and women’s rights. After leaving the White House, Mrs. Ford helped reduce the social stigma surrounding addiction and inspired thousands to seek much-needed treatment. While her death is a cause for sadness, we know that organizations such as the Betty Ford Center will honor her legacy by giving countless Americans a new lease on life.”

Former First Lady Nancy Reagan also offered a tribute in her statement: “She has been an inspiration to so many through her efforts to educate women about breast cancer and her wonderful work at the Betty Ford Center. She was Jerry Ford’s strength through some very difficult days in our country’s history, and I admired her courage in facing and sharing her personal struggles with all of us.”

Former President George H.W. Bush added, “No one confronted life’s struggles with more fortitude or honesty, and as a result, we all learned from the challenges she faced.”

Ford was an accidental first lady who had looked forward to her husband’s retirement from political life until Richard Nixon chose him to replace Vice President Spiro Agnew, who had resigned amid allegations of corruption. When turmoil engulfed Nixon during the Watergate scandal, she told anyone who asked that she did not want to be first lady, but the job became hers when the president resigned on Aug. 9, 1974.

The groundbreaking role she would play as first lady may have been foreshadowed in President Ford’s inaugural address.

“I am indebted to no man and only to one woman — my dear wife, Betty,” he told the nation. Over the next 800 days of his tenure, she would outshine him in the polls, and when he ran for election in 1976, one of the most popular campaign buttons read “Betty’s Husband for President.”

Her taboo-busting honesty — about abortion, sex, gay rights, marijuana and the Equal Rights Amendment — was a bracing antidote to the secrecy and deceptions of the Watergate era. Although her opinions may have cost him some votes, historians and other observers would argue later that Gerald Ford could not have ended “our long national nightmare” without Betty leading the way.

“I was terrified at first,” she once said about her sudden elevation to first lady. “I had worked before. I had raised a family — and I was ready to get back to work again. Then, just at that time, this thing happened. And I didn’t have the vaguest idea what being a first lady was and what was demanded of me.”

The solution? “I just decided to be myself,” she said.

Ford caught the attention of a scandal-weary America with her opinions on her children’s dating habits and their possible marijuana use, and on her and her husband’s decision not to follow the White House tradition of separate bedrooms.

She enthusiastically campaigned for feminist causes that she believed in — the Equal Rights Amendment, for example, and the nomination of a woman to the Supreme Court. Her vigorous support of the women’s movement inspired leading feminist Gloria Steinem to remark that she “felt better knowing that Betty Ford was sleeping with the president.”

Two months after Ford moved into the White House, a malignancy was discovered in her right breast. She underwent a radical mastectomy, followed by chemotherapy.

At that time, breast cancer was a taboo subject, so it was remarkable news that she not only disclosed the illness but openly talked about it and her treatment. “It’s hard for anyone born perhaps after 1980 or even in 1970 to understand that these things were not talked about,” Dr. Patricia Ganz, director of cancer prevention and control research at UCLA’s Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center, told The Times in 2006.

“They were very stigmatizing. A woman didn’t dare mention to her friends, employer, extended family that she had breast cancer,” Ganz said. Ford’s belief that if it could happen to her, “it could happen to anyone,” heightened public awareness of the disease. The American Cancer Society reported a 400% increase in requests about breast cancer screenings, and tens of thousands of women sought mammograms. Among those helped by her frank attitude was Happy Rockefeller, the wife of Vice President Nelson Rockefeller, who discovered she had breast cancer and subsequently underwent a mastectomy.

The public outpouring led Ford to realize that when she spoke, people listened. For the rest of her White House days, she would use her position as a bully pulpit to advance the causes and issues she believed in.

She “made the personal political, creating new options for women and for political wives,” historian Mary Linehan wrote in an essay for the book “The Presidential Companion: Readings on the First Ladies.” In so doing, Ford redefined the role of the first lady for herself and those who followed.

During the ratification process for the Equal Rights Amendment, which ultimately failed to win approval, she wrote letters and telephoned state lawmakers in an attempt to enlist their support. Her outspoken advocacy alienated ERA foes, who at one point organized an angry picket line in front of the White House.

She startled a nationwide television audience one Sunday evening shortly after becoming first lady, telling CBS “60 Minutes” interviewer Morley Safer that she wouldn’t be surprised if her daughter Susan, then 18, decided to have an affair. Ford said that she would “certainly counsel her and advise her on the subject, and I’d want to know pretty much about the young man that she was planning to have the affair with.”

She went on to say that she assumed her children had tried marijuana and called the Supreme Court decision supporting a woman’s right to have an abortion “the best thing in the world … a great, great decision.”

Photos: Life of former First Lady Betty Ford

The interview unleashed a torrent of negative mail to the White House. Some constituents said her comments reflected a breakdown of American morality and that they would not vote for her husband when he ran for election.

In 1976, President Ford lost to Jimmy Carter by fewer than 2 million votes but not because of his wife’s outspokenness; analysts attributed his loss largely to his pardon of Nixon. National pre-election polls showed that almost three-quarters of Americans thought Betty Ford was an excellent first lady, and solid majorities agreed with her stands on controversial subjects, including whether she was right to talk about what she would do if Susan Ford was having an affair.

Although she was often counseled to temper her public remarks, Ford remained true to herself and held little back. The world found out that Gerald Ford was her second husband; she divorced the first, a furniture company representative named William Warren, on grounds of incompatibility after five years of marriage.

She offered information, even when she wasn’t asked. Reporters “asked me everything but how often I sleep with my husband,” she once said. “If they’d asked me that I would have told them: ‘As often as possible.’ ”

Her husband had been minority leader of the House when he was selected by Nixon in 1973 to replace Agnew, who had resigned after pleading no contest to federal charges of income tax evasion. Ford served as vice president for only eight months, before Nixon himself resigned in the face of impeachment and certain conviction in the Senate for his role in the Watergate scandal.

At the start of her husband’s abbreviated White House term, Ford indicated that she would prefer that her husband not run for the presidency in 1976. She later changed her mind, and campaigned for him enthusiastically. When it was all over, because Ford’s voice had been reduced to a whisper by campaign speeches, he had his wife read to the press the telegram he had written conceding to Carter.

She was born Elizabeth Ann Bloomer in Chicago on April 8, 1918, and moved with her family to Grand Rapids, Mich., when she was 3. She was a vivacious child — her mother liked to say that Betty “popped out of a bottle of champagne.” Although her father, a traveling salesman, was often away from home, she had a sunny childhood with few clouds until she was 16, when her father died of carbon monoxide poisoning while working on the family car.

At the age of 8, she began studying dance, which developed into a lifelong interest. After graduating from Grand Rapids’ Central High School in 1936, she attended two summer sessions of the Bennington School of Dance in Vermont, where she met Martha Graham. She continued her dance career, studying with Graham for two years in New York, eventually as a member of the Martha Graham Concert Group. She also modeled part-time with the John Powers Agency.

She returned to Grand Rapids in 1941 and became a fashion coordinator for a department store. She also formed her own dance group and taught dance to disabled children. She decided to remain in Michigan. She continued to dance until she pinched a nerve in 1964 while trying to raise a window. The injury led her to begin taking prescription painkillers.

Not long after she divorced her first husband, she met Gerald Ford, who had recently returned to Grand Rapids after serving in the Navy in World War II. Their marriage was delayed for several months because Ford, a lawyer, was running for U.S. representative from Michigan’s 5th Congressional District.

Ford was immediately caught up in his new work, and Betty Ford was determined to keep up with him. But soon she had other things to do: the Fords had four children within seven years.

“That was perhaps more than I expected,” Mrs. Ford told Steinem in 1984.

In her 1973 interview with The Times, shortly after Ford was appointed vice president, she described the tensions and loneliness she suffered as a congressman’s wife, problems that she said were compounded by the constant discomfort of the pinched nerve. In 1972, she began to see a psychiatrist, who also asked to see her husband.

“He saw him a couple of times,” she said. “But it had nothing to do with Jerry. It was just his dumb wife.”

She added: “It was helpful talking over the problems of being here alone quite a bit of the time and having to make decisions about the children at a crucial stage in their growing up. I had been assuming the role of both mother and father.”

The pressures escalated in the White House, however, and Ford began to rely on tranquilizers and alcohol to cope. She later told Barbara Walters that she was taking 20 to 30 pills a day.

Her addictions, she said some years after leaving Washington, was “an escapism from all that living in a fishbowl to a certain extent and the pressure of always having to be ‘on’ when perhaps you feel very ‘un-on’ or very down inside.”

A year after her husband’s loss to Carter, Ford’s problems worsened. She was dependent on “sleeping pills, pain pills, relaxer pills and the pills to counteract the side effects of other pills,” she wrote in her 1987 book “Betty: A Glad Awakening.” She had a glass of vodka or bourbon before dinner and another after dinner. She canceled or missed dates, shuffled around the house in her bathrobe, forgot important conversations with her children and spoke in a slur; she was groggy most of the time, walked unsteadily and cracked a rib in a fall. “I was dying,” she said, “and everybody knew it but me.”

Their daughter Susan was so alarmed by her mother’s condition that, one week before her mother’s 60th birthday — on April Fool’s Day, 1978 — she arranged an intervention. Family members, accompanied by a medical team, gathered unannounced at the house in California and one by one told her how her addictions were hurting them and destroying her.

Their remarks cut her to the core; she was angry and resentful. “You hit the wall,” she told Life magazine years later, recalling that day. “When you hit the wall, you better find a way to either go around it or over it. The disease (of addiction) is the wall.”

When the emotionally grueling session was over, she decided to scale the wall. She publicly announced that she had an addiction problem and checked into the Long Beach Naval Hospital for a month of detox and therapy.

When she was well on the road to recovery, she had a facelift “to go with my beautiful new life.” Of course, she told everyone about that too.

Ford figured if addiction could happen to her, it could happen to anyone, and she turned her energies toward helping others. With her neighbor, tire magnate Leonard Firestone, she raised $5 million to build an 80-bed facility in Rancho Mirage. Since its opening in October 1982, it has treated more than 75,000 people, including such well-known personalities as Peter Lawford, Liza Minnelli, Johnny Cash and Mary Tyler Moore, and it remains the most prestigious name in the drug and alcohol rehabilitation field.

“Rarely does anyone’s name become a noun. Everyone knows what you’re talking about if you say, ‘I’m going to Betty Ford,’ ” John Robert Greene, a historian and Ford biographer, told the Baltimore Sun in 2006.

In her 80s, Betty Ford remained actively involved as chairwoman of the board and regularly welcomed new residents. Once a month, she started a meeting with patients by saying: “Hello, I’m Betty Ford, I’m an alcoholic and an addict.”

“She speaks as one recovering alcoholic to another,” the late actress Elizabeth Taylor, one of the facility’s most celebrated residents, told People magazine of Ford. “There are no airs about her being first lady.”

Ford, who lived in Rancho Mirage, is survived by her sons Michael Ford, John “Jack” Ford and Steven Ford; daughter Susan Ford Bales; grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

A service is planned in the Coachella Valley. The former first lady will be buried next to her husband at the presidential library in Grand Rapids.

Photos: Life of former First Lady Betty Ford

Cimons is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer.

Los Angeles Times staff writer Elaine Woo and former staff writer Claudia Luther contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.