America’s first conservatives

- Share via

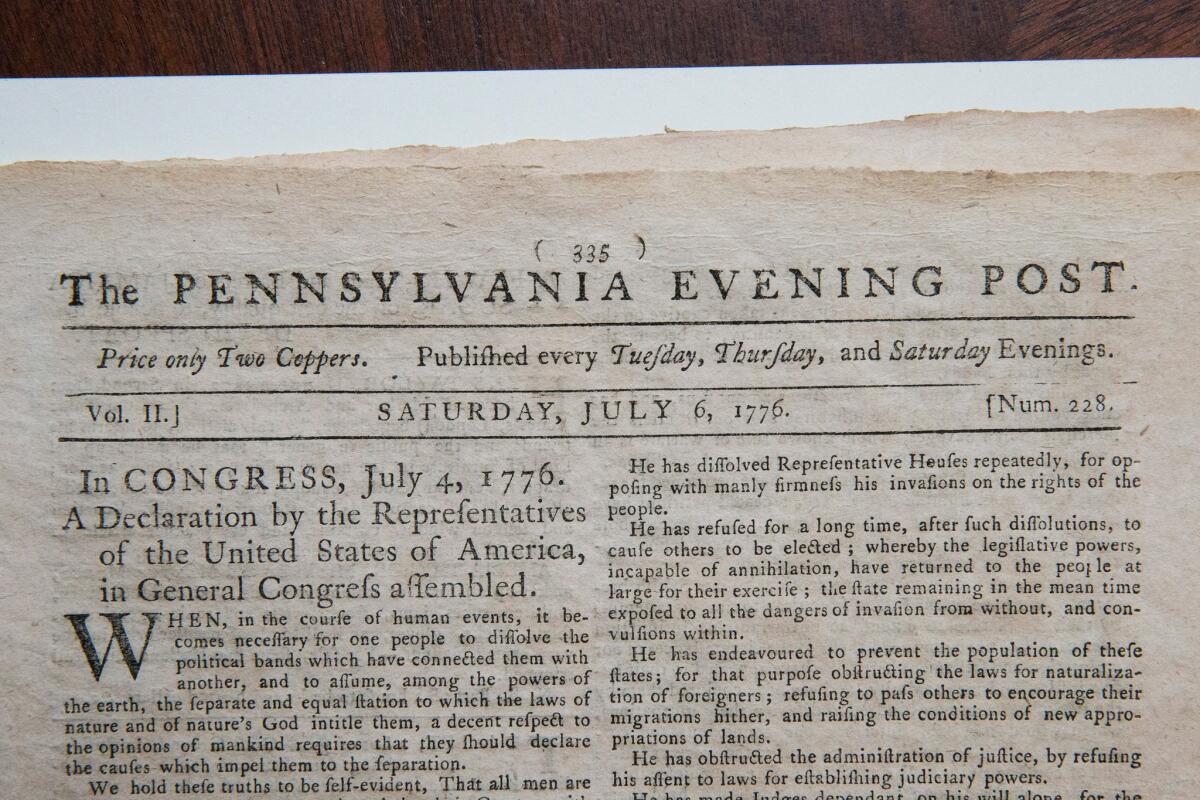

Had it not been for America’s founding conservatives, we would not be celebrating Independence Day on July 4. In fact, it’s unlikely we would be celebrating our independence at all.

Few people today realize how similar the Revolutionary era was to our own: Endless war, financial crashes and mounting public debt, popular outrage against rich bankers and taxation, and such bitter partisan dispute that Congress was frequently deadlocked for months on end.

That the American Revolution was filled with political strife was well established at the start of the 20th century. During the Cold War, however, historians deliberately downplayed these differences. As a result, the story of the founding conservatives was lost.

PHOTOS: Celebrating Independence Day

Largely forgotten today, the nation’s first conservatives were collectively as important as its famous revolutionaries and firebrands like Franklin, Jefferson, Adams and even, to some degree, Washington. These men were not Loyalists. They were among the most ardent defenders of American rights, and many fought with distinction against British Redcoats. But they respected hierarchies and custom, revered the military and championed free-market capitalism. They were the polar opposite of, say, a Thomas Paine, the Revolution’s pamphleteer, who proselytized for a guaranteed income and agrarian rights along with fighting the British.

No issue divided America’s patriots more than independence itself. By 1775, advocates for immediate separation were battling those who counseled caution in the Continental Congress. Led by Philadelphia lawyer and writer John Dickinson, the founding conservatives feared the social upheaval that independence would bring. If not handled carefully, a revolution might trigger “the dissolution of every kind of authority,” warned James Wilson, one of America’s greatest legal minds and a future Supreme Court justice.

Before independence could safely be attained, America needed time to prepare, Dickinson argued. For more than a year, he and his allies worked to shore up the Colonies’ military, seek foreign assistance and unite a deeply divided populace. Separate too soon, they warned, and Britain would crush the nascent state. Their arguments persuaded Congress to delay a vote on independence until the beginning of July 1776.

On July 1, 51 delegates assembled at Philadelphia’s State House for what John Adams called “the greatest debate of all.” The day was hot and damp. To the discomfort of all, the windows and doors were shut to guard against eavesdropping British spies. With a bang of his gavel, John Hancock called for quiet as a motion to declare independence was read aloud.

Dickinson arose, tired and pale. He had slept little the past few nights, having worked feverishly on the speech he was about to give. He knew revolution was inevitable. Still, he was prepared to argue for caution one last time. For more than two hours he warned of the blood, chaos and economic ruin war would bring. The fight would not be over as quickly as its proponents suggested.

“When our enemies are pressing us so vigorously, when we are in so wretched a state of preparation, when sentiment and designs of our expected friends are so unknown to us,” he said, “I am alarmed at this declaration being so vehemently presented.” He concluded by predicting that several decades hence, America would divide into two nations, a North and a South.

For a long time no one spoke, reflecting on Dickinson’s sober words. Rain started to pelt the windows. Finally, John Adams, long an advocate for independence, rose to argue the other side. He was “not graceful nor eloquent,” Thomas Jefferson noted, but he spoke “with a power of thought and expression that moved us from our seats.” A binding vote would be taken the next day.

That night Dickinson held a vigil with his fellow Pennsylvania delegate Robert Morris, another conservative. They decided they were Americans and could not abandon their country. They also could not vote contrary to their consciences, which urged against immediate revolt. And yet they knew that for the new nation to stand a chance, every colony had to vote for independence. The next day, Tuesday, July 2, amid thunderclaps and rain, the two abstained, allowing Pennsylvania’s delegation to approve the measure by a single vote. Independence was unanimous.

Even John Adams admitted the wisdom of delaying independence. “This will cement the union, and avoid those heats, and perhaps convulsions, which might have been occasioned by such a declaration six months ago,” he wrote on July 3.

On July 4, 1776, the day Congress formally approved Jefferson’s Declaration of Independence, 113 hulking British transports appeared off the coast of New Jersey. The brand-new state begged Congress for help. Dickinson, a militia colonel, became the first commander to lead his forces out of Philadelphia and begin the weeklong march to join Washington’s force in New York. He would be one of the few members of the Continental Congress to march off to war . Somehow that same tumultuous week, he also found time to draft the Articles of Confederation

Dickinson (who never signed the declaration), Morris (who ultimately did) and their fellow founding conservatives would leave an indelible impact on the Revolution. Morris, the richest merchant in America, single-handedly bankrolled the Continental Army and propped up the national economy at the end of the war. Major Gen. Philip Schuyler of New York engineered the watershed victory at Saratoga. John Rutledge, the governor of South Carolina, led his state’s resistance after the British seized Charleston. And Gouverneur Morris, of New York , literally wrote the Constitution, beginning with the words, “We the People.”

On Independence Day, it is vital for modern conservatives to remember how their forebears in 1776 put patriotism before politics and compromised for the good of the nation. It is vital for all Americans, Democrats and Republicans alike, to recognize the lasting debt we owe the founding conservatives.

David Lefer, a professor at New York University, is a registered Democrat and the author of “The Founding Conservatives: How a Group of Unsung Heroes Saved the American Revolution.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.