Giant black hole is seen gobbling up a star

- Share via

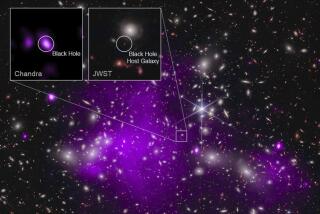

Back when single-celled organisms ruled Earth, a gigantic black hole lurking quietly at the center of a distant galaxy dismantled and devoured a star.

On Wednesday, astronomers reported that they watched the whole thing unfold over a period of 15 months starting in 2010, the first time such an event had been witnessed in great detail from start to finish.

“The star got so close that it was ripped apart by the gravitational force of the black hole,” said Johns Hopkins University astronomer Suvi Gezari, lead author of a paper about the observations that was published online by the journal Nature.

Studying the radiation that escaped the catastrophe — signals that took about 2 billion years to reach Earth — Gezari and her colleagues were able to determine the size and composition of the ill-fated star and suss out the characteristics of the black hole that destroyed it.

Astronomers call these star-obliterating events tidal disruptions. The process is similar to — but far more violent than — tides on Earth, which are created by the moon’s gravitational tug on the planet and its oceans.

Estimated to occur only about once every 10,000 or so years in each galaxy, tidal disruptions are extremely difficult to spot. But astronomers seek them out because they make black holes visible, and therefore possible to study.

Starved of fuel, most black holes normally lie dormant and invisible, said Michael Eracleous, an astronomer at Penn State University who was not involved in the research.

But during a tidal disruption, energy produced by their interactions with stellar gases produces intense flares of radiation.

“For a brief period of time the black hole lights up and makes itself known,” Eracleous said.

Gezari and her colleagues used two telescopes — one in Hawaii that detected visible light and another perched in orbit that sensed ultraviolet radiation — to scan the sky for possible tidal disruptions, which appear as bright flashes that slowly fade away.

On May 31, 2010, they noticed a galaxy “that was just sitting there” quickly increase in brightness by a factor of hundreds, Gezari said.

Measuring its radiation with the telescopes and a host of other instruments, they were able to confirm that they were witnessing the early stages of a tidal disruption.

They were also able to reconstruct the death throes of the devastated star.

Veering close to the black hole — about the same distance as Mercury lies from the sun — the gaseous star was stretched out and torn asunder by the black hole’s intense gravity.

“It turned into this really thin piece of spaghetti,” Gezari said.

About 76 days after the star was ripped apart, the black hole began devouring its remains, taking at least a year to finish off the meal.

The scientists calculated that the black hole’s mass was 3 million times greater than that of the sun, which itself has four times the mass of the destroyed star. Through spectroscopy, they also discovered that the star was made up primarily of helium, suggesting that the star’s outermost hydrogen layers had been stripped away by the black hole long before.

UC Berkeley astronomer Eliot Quataert, who was not involved with the research, said that scenario was surprising.

“It is the most interesting thing, in my view, about this,” he said. “It’s a window into how stars may not be destroyed by single, one-off events.”

Finding more of these star-gobblers to study could help theorists better understand many aspects of the physics of black holes, Quataert said.

“People really want to understand the connection between how galaxies grow and evolve with time and how that relates to the massive black holes at their centers,” Gezari said.

Scientists have been able to catch glimpses of only a dozen or so probable tidal disruptions, Eracleous said. But systematic searches like the one that led to the discovery announced Wednesday will make it possible for astronomers to spot these stellar murders much more often.

By the end of the decade, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope in Chile should be operational; it’s expected to detect 60 to 250 such events every year, he said.