George Holliday, man who filmed Rodney King video that forever changed L.A., dies

- Share via

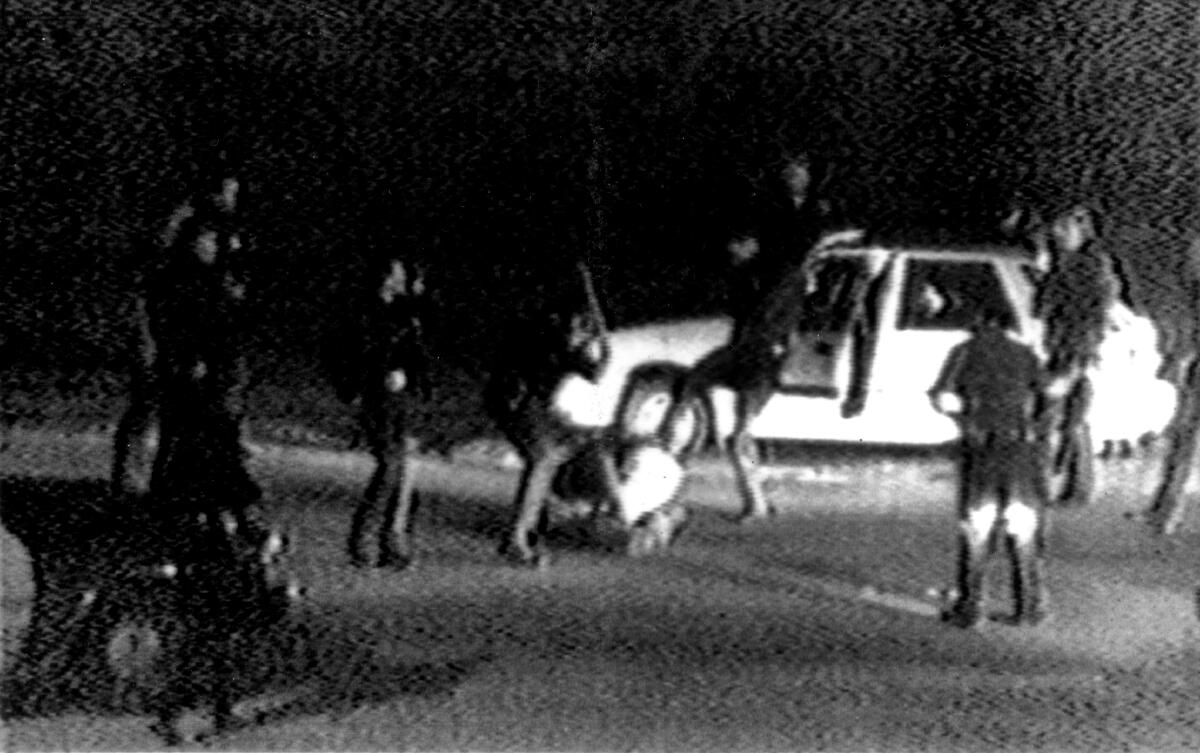

The video was less than nine minutes long, dark, grainy and badly out of focus. But it changed L.A. in ways that were unfathomable and dragged George Holliday into a life he never bargained for.

Shot with a bulky Sony Handycam, the video of the Rodney King beating in 1991 tore open a city already heaving with racial tension, an era when the Los Angeles Police Department was all but an occupying force in the city’s Black neighborhoods, arriving with tanks, battering rams and brute force.

And when the four officers who beat King were acquitted the following year, the city exploded in protest and violence, thick smoke curling into the sky from Koreatown to South L.A. By the time it was over, more than 50 people had been killed and more than 2,300 were injured. The scars — both to the city’s urban core and to the psyches of its residents — remained in plain view for decades.

For Holliday, it was like being hurled over a cliff. Reporters lurked outside his Lake View Terrace apartment, death threats arrived in the mail, and his efforts to receive just compensation for one of the most infamous videos of the time vaporized again and again.

Still hard at work as a plumber, Holliday died Sunday of complications of COVID-19, said Robert Wollenweber, a fellow plumber and close friend. Holliday was 61 and had been in a Simi Valley hospital since mid-August.

Holliday had just gone to bed when he heard the wail of sirens. He pulled on his trousers, grabbed his footlong video camera, stepped onto the balcony and hit the record button. From beginning to end, it was raw, bloody footage, with the officers beating, clubbing and shooting King, who was Black, with a Taser before finally tossing a sheet over his face, as if he were dead.

For the record:

2:40 p.m. Sept. 21, 2021An earlier version of this story said the Rodney King video was confiscated from KTLA by the Los Angeles Police Department. It was seized by the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office.

Holliday said he called the LAPD to ask what was going on and to tell them he’d videotaped the beating. But he said the dispatcher hung up on him. He tried again the next morning and then finally called KTLA-TV Channel 5 instead. Armed with a subpoena, investigators with the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office later seized the tape. But by then, copies of the video were multiplying rapidly, an early-day viral sensation.

When the four officers were tried for assault and use of excessive force in 1992, Holliday’s video was the prosecution’s most damning piece of evidence. After seven days of deliberations, the largely white jury returned not-guilty verdicts.

The city, indeed the nation, was stunned.

“This jury’s verdict will not blind us to what we saw on that videotape,” said Tom Bradley, L.A.’s only Black mayor.

“Viewed from outside the trial, it was hard to understand how the verdict could possibly square with the video,” President George H.W. Bush said. “Those civil rights leaders with whom I met were stunned. And so was I, and so was [First Lady] Barbara and so were my kids.”

In ways that then couldn’t be seen, Holliday’s simple act of hoisting a video camera to his shoulder was probably one of the first flickers of the citizen journalist movement to come, in which everyday people would record and disseminate video snippets of unfolding events, from Eric Garner to George Floyd, both of whom died at the hands of police officers.

By every possible measurement, Holliday’s video ignited a revolution. It helped usher in an era when police behavior and public accountability were shaped and influenced by even the most casual smartphone users, who could rocket disturbing videos around the globe on Twitter, Instagram and other social media platforms.

Police departments also embraced — some slowly, some with enthusiasm — body cameras that would record patrol officers’ interactions with everyone, from dangerous felons to routine traffic citations. The devices, meant to ensure that officers were meeting department standards, at times also helped police disprove false claims.

“The Rodney King video was the Jackie Robinson of police videos,” the Rev. Al Sharpton said.

After the acquittal, Holliday watched the five days of violence in horror. Customers told him his video had caused the upheaval. He found a note tucked under a windshield wiper blade of his work truck: “Be careful when you start your car in the morning.” He worried the police would target him.

“There was a sea of reporters every day,” Holliday told The Times in 2006. He said his wife was too afraid to leave their apartment, and then finally did leave — for good. A second marriage also fell apart. And his legal efforts to collect compensation for his video only resulted in mounting bills from lawyers. Raised in Argentina, he contemplated returning to his homeland.

Struggling to pay his bills, he put his old video camera — by then no longer working — on the auction block in 2020, with an opening bid of $225,000. It sold for an undisclosed sum.

“Look, I’m still a plumber, even after all this,” he told the New York Times.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.