Bob Dole, forever the presidential hopeful, dies at 98

- Share via

A son of the heartland, a veteran disabled in one of the nation’s great wars and a leader in the political dramas that shaped the country, America may have served up no purer emblem of the nation’s triumphs and challenges in the second half of the 20th century than Bob Dole.

He was a state legislator, House member, Senate leader, national spokesman for a sturdy brand of common-sense conservatism, four times a candidate for national office and always an advocate for the country’s farmers and war veterans.

He dominated the life of the Senate for a decade, was a leading Republican in Washington and emerged as a potent symbol, not only for Democrats who derided him as an obstructionist, but also for the new breed of hard-right Republicans who considered his style too accommodating, his ideology too squishy and his identification with the Washington establishment too strong.

Nonetheless, no Republican, aside from Richard M. Nixon, was at the center of Washington and the searing battles within the Republican Party for so long and with so great an impact.

Diagnosed with Stage 4 lung cancer in February, Dole died early Sunday in his sleep at age 98, according to the Elizabeth Dole Foundation. It did not say where he died or list a cause.

“Bob was an American statesman like few in our history. A war hero and among the greatest of the Greatest Generation. And to me, he was also a friend whom I could look to for trusted guidance, or a humorous line at just the right moment to settle frayed nerves,” said President Biden, who served with Dole in the Senate. “I will miss my friend.”

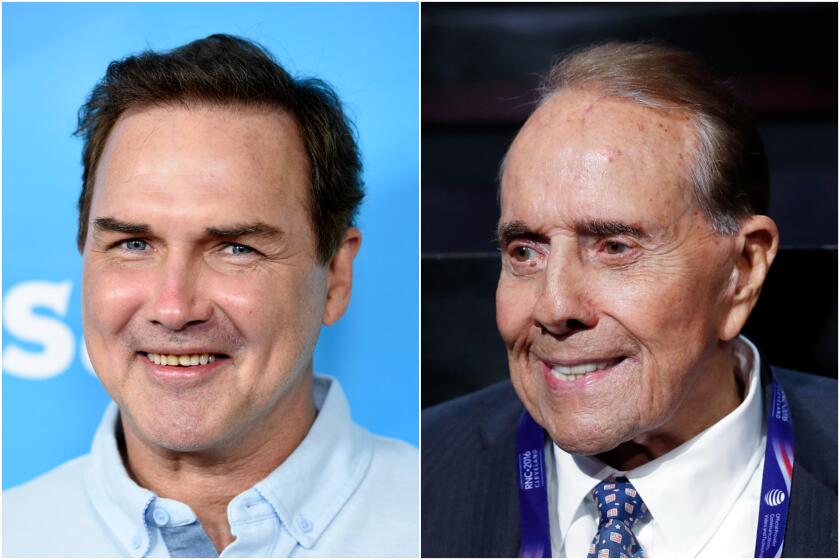

Before he died Sunday, former Senate leader Bob Dole hailed late comedian Norm Macdonald’s ‘Saturday Night Live’ impression of him.

House Speaker Nancy Pelosi praised Dole and ordered flags at the U.S. Capitol be flown at half-staff.

“From the battlefield to the United States Senate, he served our country with great integrity,” Pelosi said. “He was a man of his word.”

Dole’s lasting impact extended long past his retirement — he worked tirelessly for the election of his wife, Elizabeth Hanford Dole, to the Senate in 2002, and joked that he and Bill Clinton, his rival in the 1996 race, would someday compete to be president of the Senate spouse club.

In a heartbreaking coda to his public life, Dole, 89 years old and using a wheelchair, returned to the Senate in December 2012 and appealed to his former colleagues to ratify a United Nations convention on disability rights that was modeled on the legislation he crafted himself in the chamber. The treaty failed and Dole was wheeled out of the chamber by his wife.

Dole lost the 1996 presidential race to Clinton despite a spirited challenge, a series of daring gambles and a brave campaign finale of 96 hours of grueling air travel that left the Kansan hoarse and exhausted — but failed to persuade voters that a 73-year-old World War II veteran was the man to lead the nation into the 21st century.

In many ways Dole’s general-election campaign was an anticlimax to the greater dramas of his life. For years he sought and was denied his party’s nomination for president, winning it 1996 only after a difficult struggle with two foes whose vision of the Republican Party and its future couldn’t have been more different from his — publisher Malcolm S. “Steve” Forbes Jr. and commentator Patrick Buchanan.

But Dole, who for decades prided himself on understanding the prevailing winds of American politics, was nonetheless willing to bend, and on the eve of the Republicans’ 1996 nominating convention reached out to a former rival, Jack F. Kemp, offering him the vice presidential nomination and embracing his notions of supply-side economics. Six months after his defeat, he startled Washington with another gesture to a party rival, offering Newt Gingrich a $300,000 loan to permit the House speaker to pay off a fine in connection with an ethics investigation.

As he aged, his impulse for political pugilism withered, permitting a tender rapprochement with his rival George H.W. Bush; in their 90s the two called each other on their birthdays and, to mark the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, appeared together in 2016 at a Texas commemoration of the attack that began the U.S. conflict with Japan in World War II.

That very day, in December 2016, news accounts reported that Dole, the only living GOP nominee to support Donald Trump for president, had helped a client by arranging a phone call between Trump and the president of Taiwan — an intercession that prompted some of those who knew Dole to wonder whether, at 93, he had been manipulated by friends or business associates.

Dole came to Washington the year John F. Kennedy was inaugurated as president, but as a young man he had strong emotional ties with Dwight D. Eisenhower, a fellow Kansan and the commander of the American force in Europe that shaped Dole’s life.

He fell into the political circle around Nixon and was Republican national chairman during the height of the Watergate scandal. He was Gerald Ford’s running mate in 1976, when he gave the nation its first taste of his sometimes harsh rhetoric when he referred to the four wars of the 20th century as “Democrat wars.” He ran against Ronald Reagan for the GOP presidential nomination four years later and finished at the back of the pack but was the president’s legislative leader for two terms.

Dole was for a time the favorite to capture the Republican nomination in 1988 and actually won the Iowa caucuses that February, but his struggle with George H.W. Bush took on a bitter tone and his eventual loss came to symbolize Dole’s failures as a national candidate — his lack of vision, his reflexive impulse to use his wit as a weapon.

Despite his midlife rivalry with Bush, he later served the president loyally, acting as his agent on Capitol Hill. So dominant was he in Congress that, though he was well over 70 and his World War II generation had been eclipsed by Clinton and the baby boomers, Dole swiftly emerged as the front-runner for the GOP presidential nomination in 1996.

Though Dole’s life was intertwined with the leading figures of Washington’s postwar political establishment, his relationship with Gingrich defined GOP politics at century’s end.

For years he and Gingrich sparred, two symbols of competing and often irreconcilable visions of Republicanism. Gingrich was a supply-sider, an economic theory that left Dole unimpressed, and an insurgent, a political tactic that left Dole cold.

The bitterness flared often, and Dole spent a decade answering Gingrich’s well-worn taunt that the Kansan was a tax collector for the welfare state. When Gingrich became speaker in 1995, Dole suppressed his skepticism, perhaps because he recognized that Gingrich now held the upper hand in GOP politics, and the two often appeared together, working in tandem.

Dole was the quintessential young man of the innocent America before World War II. His worldview, his accent, his conservatism and his life rhythms were set in Russell, Kan., far from metropolitan America and deep in grain country.

His father, Doran Dole, operated the White Front Cafe on Main Street, then ran a cream and egg station, while his mother, Bina, sold sewing machines, was an accomplished seamstress and was known for her fried chicken and cream gravy and homemade ice cream.

“Russell’s the Bob Dole difference,’’ John J. Streck, one of Dole’s high school classmates, once said. As a young man, Dole played basketball and minded the soda fountain at Dawson’s Drug. He was chosen to be the soda jerk because he was smart, efficient and honest.

“He was an all-American boy,’’ said Everett Dumler, a lifelong friend who later became manager of the small town’s chamber of commerce.

Like many young men in town, he went to war. He saw a bit of the world and then had his whole world changed. In the last weeks of World War II, in Italy, an exploding shell so racked his body that a platoon sergeant gave him a shot of morphine on the battlefield.

Then began months and years of recovery. He had a persistent fever, he lost a kidney, he shed 72 pounds. He also lost, he later admitted, his entire sense of physical robustness. His family doubted he would ever walk again.

It was a challenge greater than any presented by politics. He worked and he struggled and he worked some more, eventually being able to take a step, then a few, then to reach the end of the block. The injuries to his right hand lasted though life and he found it so painful to shake hands in public gathering that he would clutch a pen in his right hand so he could avoid the formality.

“Much of my life since April 1945,” he wrote in his memoir, “has been an exercise in compensation.”

Dole went to law school and into politics, traveling hundreds of miles in a legislative race, then thousands in a congressional contest in 1960. He wasn’t much of an ideologue, joking that he looked at the voting rolls, saw more Republicans than Democrats and decided, right there on the spot, that he was a Republican. For him, the arithmetic of politics was always more potent than the chemistry.

In Washington he was a plodder and a plotter, eventually winning notice and repeatedly winning reelection. After succeeding Howard H. Baker Jr. as Republican leader in 1985, his stature in the Senate was unapproachable. Indeed, the Senate gave order to Dole’s life. He was a master of legislation in an era of sound bites, a master of the compromise in an era when reaching across the aisle was derided.

Dole was known for the sarcastic aside but, in the halls of the Capitol, he was also remembered for the gentle gesture. Congressional workers consistently regarded him as their favorite senator. He raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for charity and, a prostate cancer survivor himself, would sometimes sit in his office as the dark thickened around Washington and call men around the country who themselves faced prostate surgery or death.

An improbable sequel to his struggle with cancer was Dole’s decision to appear in television commercials for the erectile dysfunction drug Viagra. Dole said he did the ads in an effort to further frank conversation about the disease and its effects.

The arc of Dole’s career was also shaped by women: by his mother, who gave him his sense of humor; his sisters, who encouraged him when, in the dark days of the war injury, there was no reason for encouragement, his daughter, Robin, a Washington lobbyist and friend in adulthood; and the two women he married.

Dole met his wife of 23 years, Phyllis, at an army-hospital dance and they married three months later in New Hampshire. “I remember when we were first married, I used to make shoulder pads to go under his shirts because one shoulder is shorter than the other,” she said. “He had to get his suits tailored to fit him. I cut up meat for him. I understood him physically and emotionally. He had to push awfully hard to come back from his injuries, and that is just part of him now. He worked very hard to overcome all of that.”

Later he married Elizabeth Hanford, a pioneering Republican who served as secretary of Labor and Transportation and as president of the American Red Cross but who was best-known as the other half of Washington’s ultimate power couple. At a Capitol hearing, Dole once joked that he regretted that he had only one wife to give to his country. In truth, he took enormous pride in his wife’s achievements and she in his; in the late days of the 1988 presidential race, Elizabeth Dole was more reluctant to concede than was her husband.

Dole is survived by his wife and a daughter, Robin, from his first marriage.

Shribman is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.