Pat McCormick, Seal Beach diver who won Olympic gold in the 1950s, dies at 92

- Share via

Growing up as a street kid in Seal Beach in the 1930s, Pat McCormick loved the beach, loved the water, loved competing and loved taking chances. She had no idea there were such things as Olympic Games, and diving was something kids did for fun.

But McCormick used diving to carve out her own special niche in Olympic history, in effect calling her shot. Competing in the Summer Games in Helsinki in 1952 and Melbourne in 1956, she became the first diver — and still the only woman — to sweep the gold medals in consecutive Games, twice winning in both the springboard and platform events.

Not until 1988 was that feat matched, and then it was by a male diver, Greg Louganis, who swept in Seoul after having done so in Los Angeles in 1984.

McCormick died Tuesday at the age of 92, USA Diving announced Friday.

Besides talent and a deep-seated desire to succeed, the young Pat McCormick had a devilish sense of humor. At Helsinki, she was the ringleader in a practical joke played on Avery Brundage, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee and soon-to-be president of the International Olympic Committee. A stern, aloof, unyielding champion of pure amateurism, he was not popular among the athletes.

“There were four of us and we decided we were going to put his underwear up a flagpole [in the Olympic village],” McCormick told TeamUSA.org in 2012.

Enlisting the aid of a USOC official, McCormick sneaked into Brundage’s room, pilfered the underpants and proceeded with the ceremony.

“I ran out and we got in line,” McCormick said. “We had gotten all dressed up and we marched out and took our hats off. I raised the ‘flag.’ Everybody stopped and thought, ‘Isn’t that sweet!’ — until they looked up. And we got the heck out of there.”

By then, McCormick was quite used to getting “the heck out of there.” Born Patricia Joan Keller on May 12, 1930, she grew up tagging along with an older brother while their divorced mother worked as a nurse during the Depression.

“I was a tough little street rat,” she told The Times in 1987. She also was a miniature beach bum. “Growing up, I’d always been in the water. . . . I swam in the channels and the harbor. And I’d race anybody who’d race me.”

She hung around Santa Monica Beach and Muscle Beach in Venice, where the bodybuilders tossed her around in their routines, and she and her brother dived off the Los Alamitos Bridge in Long Beach.

“Sometimes, we’d wait until boats were coming into the harbor and do cannonballs, splashing them,” she recalled often. “They called me Patsy Pest.”

Eventually, though, people took note of her diving. At 14, she won the Long Beach women’s one-meter diving cup and was invited to join the Los Angeles Athletic Club team. By 1948, at 17, she had her sights set on making the Olympic team but missed — by one-hundredth of a point.

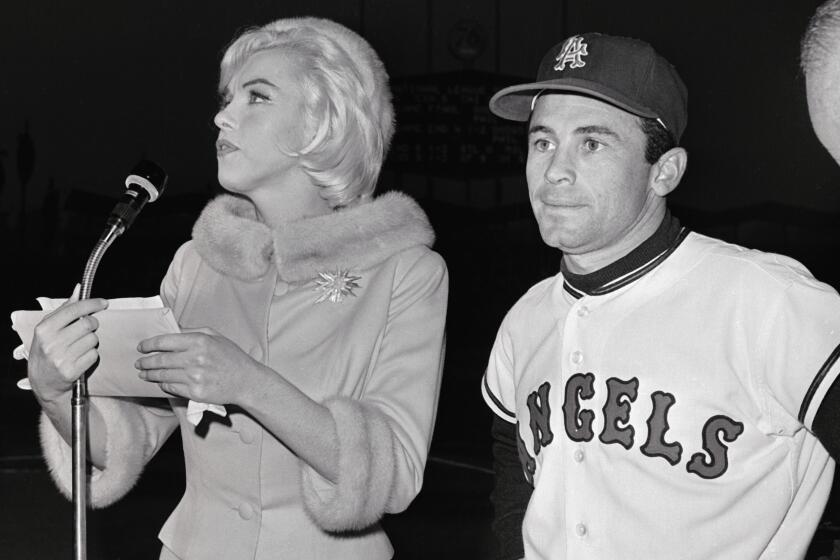

Albie Pearson, who was once known as the “Littlest Angel” standing at just five feet, five inches tall, was beloved as an Angel.

“Because of that failure, I started dreaming of the next Olympics,” she said. “I was standing there, crying, after I came up short and that’s when I decided I would win a gold medal in the next Olympics. Then I thought, ‘Why not go to two Olympics and win four gold medals?’ “

Which is precisely what she did. At Helsinki, by then married to Glenn McCormick, an airline pilot who doubled as her coach, McCormick, accustomed to doing dives that were deemed too tough for women in international competition, dominated. Only, however, after a serious scare. In an exhibition at Edwards Air Force Base about six weeks before the Olympic trials, she hit bottom, opening a large gash in her head. A doctor stitched the wound, telling her she’d have to miss the Olympics.

“I said, ‘Sir, is there anything structurally wrong with my head?’ “ McCormick recalled. “He said, ‘No,’ and had this little smile and said, ‘I’ve never seen such a hard head.’ “

At Melbourne, only eight months after giving birth to a son, she was dominant again in the 3-meter springboard event, to the extent that she didn’t need to dive in the finals.

The 10-meter platform event was a different story. Teammates Juno Irwin and Paula Meyers both outperformed her and McCormick was fourth after the first day’s competition.

She recalled, “I remember . . . thinking, ‘OK, kid, you can live a lifetime in a moment and this is it.’ “

She scored 7s and 8s — 10 is perfect — the next day in the finals, moving into the lead on her sixth of seven dives. The competition was so close, though, that she needed her last dive, a forward 2½ somersault, to be the best of her life if she was to win. And it was.

“ ... I hit that tower so hard, you could just see it shake,” she said. “When I popped up, I heard 10, 9½ and 10.”

She retired from competitive diving after that, having won 27 national championships and a Pan American Games gold medal, besides her Olympic haul. She would later win the Sullivan Award as amateur athlete of the year and the Babe Zaharias Award as woman athlete of the year, among a host of other awards. She is in several halls of fame, chief among them the U.S. Olympic Hall and the International Swimming Hall.

She continued exhibition diving for several years, modeled Catalina swimsuits and, over a period of 13 years, earned two college degrees. Later, after going through a divorce, she delivered motivational speeches, served on the Los Angeles Olympic Organizing Committee in 1984 — her daughter Kelly won a silver medal in diving in those Games — trained therapy dogs and established the Pat McCormick Educational Foundation to help at-risk youngsters get through school.

She also climbed Mt. Kilimanjaro and boated down the Amazon River.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.