Pat Robertson, founder of Christian Broadcasting Network and Christian Coalition, dies

- Share via

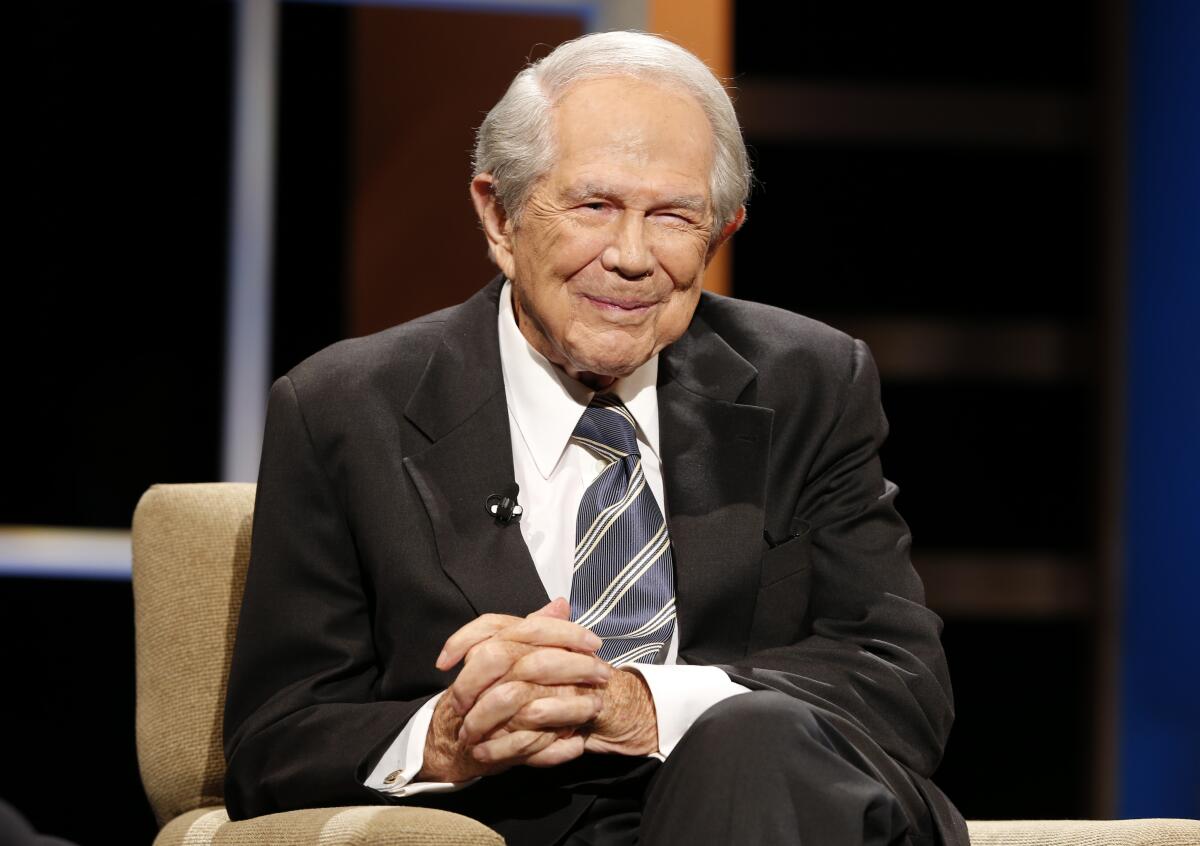

Pat Robertson, the charismatic religious broadcaster who parlayed the success of his pioneering television ministry into the first serious bid by an evangelical leader for the U.S. presidency, then launched the influential Christian Coalition advocacy group, has died. He was 93.

Robertson’s death Thursday was announced by his broadcasting network. No cause was given.

The founder of the Christian Broadcasting Network and host of its enormously popular, long-running program, “The 700 Club,” had suffered a stroke in 2018.

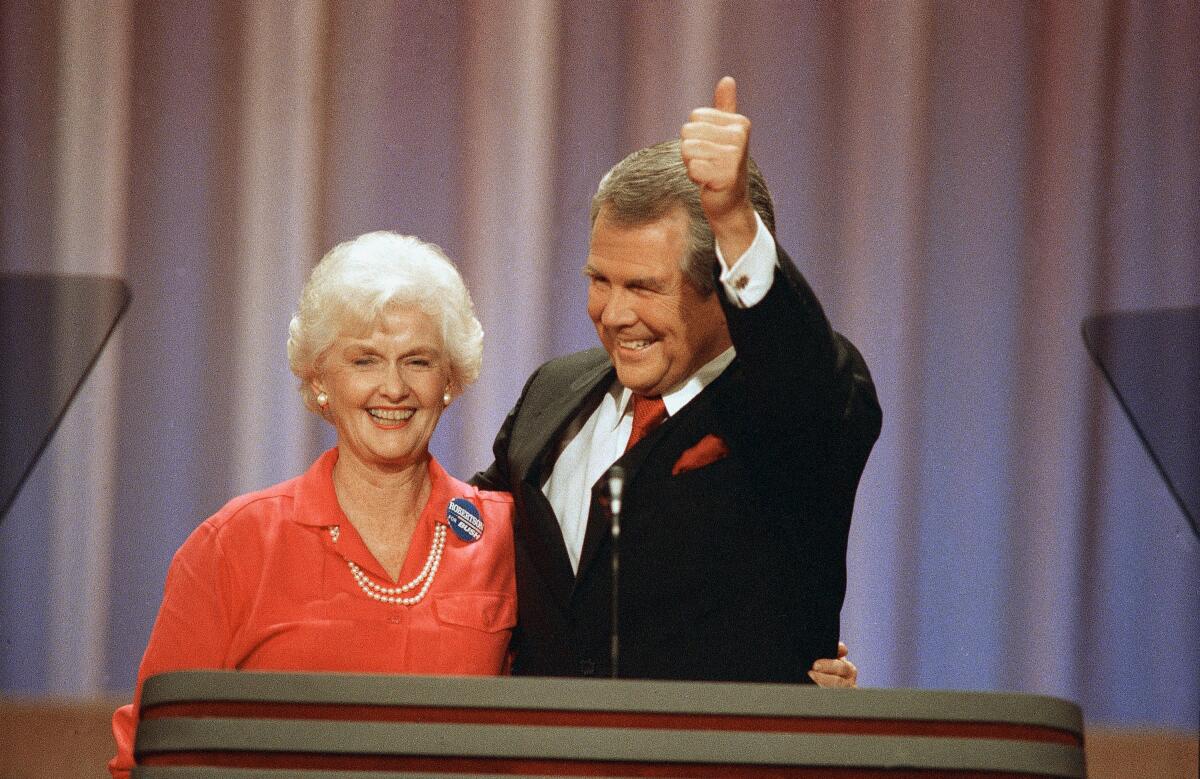

A former Southern Baptist minister who said God had inspired him to run for president, Robertson made a strong start in his campaign for the 1988 Republican nomination, stunning better-known opponents, including Vice President George H.W. Bush, the eventual nominee, by finishing near the top in Iowa and other early contests.

Although poor showings in later primaries soon forced him to withdraw, Robertson’s campaign became a political springboard. In 1989, he founded the Christian Coalition, which gave conservative Christians a voice in the nation’s capital and helped turn the religious right into a well-organized political movement.

“He saw the possibilities,” said Laura R. Olson, a Clemson University political science professor and expert on religion and politics. “Pat Robertson was absolutely brilliant at taking his success from the presidential race and transforming that into a powerful interest group.”

A Yale law school graduate and son of a U.S. senator, Robertson had the education, media skills and political experience to build on the foundation laid by another group with conservative Christian roots.

In 1979, the Rev. Jerry Falwell founded the Moral Majority, which rallied once-apolitical fundamentalist and evangelical Christians into an electoral force. By 1989, amid lackluster fundraising, it was disbanded and the Christian Coalition was born.

A fundamentalist preacher like Falwell, Robertson urged Christian conservatives to fight what he saw as America’s drift toward moral decay. He pointed to legalized abortion, homosexuality and AIDS, as well as government policies he saw as anti-family and anti-God.

But the approach favored by Robertson and Ralph Reed, the political activist he hired to run the Christian Coalition, was more sophisticated than the often-blistering attacks of Falwell, creating a more polished style of Christian conservatism. “Robertson took what Falwell created, refined it and ensured that it continued,” Olson said.

With an army of fervent followers, Robertson and his grassroots coalition promoted conservative Christian candidates and traditional values across the U.S. By 1995, the group claimed 1.6 million members in 1,600 chapters. The following year, its financial peak, it took in contributions of nearly $25 million.

Enthusiastic and informal — viewers and most others knew him simply as “Pat” — Robertson shot to fame in the 1970s as the host of “The 700 Club,” a groundbreaking religious variety show that aired daily on his Christian Broadcasting Network.

He combined evangelistic fervor with a comfortable on-air style that drew comparisons to the most popular talk show hosts of the day, including Johnny Carson and Merv Griffin.

Mixing news with music, a call-in advice segment and interviews with key religious and political figures, the “700 Club” made Robertson a familiar face across the U.S. By the 1980s, the Christian Broadcasting Network, the media empire he built from his 1959 purchase of a single Virginia television station, reached about 30 million homes and grossed more than $200 million a year.

“He appealed to a rising middle class among evangelicals,” said John C. Green, senior fellow at the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life.

Yet Robertson, known for his business and political acumen, also had a history of incendiary remarks that repeatedly thrust him into the headlines, particularly in his later years.

In 2005, he called on the U.S. to assassinate Venezuela’s leftist president, Hugo Chavez, saying it would be “a whole lot cheaper than starting a war.” A few months later, he suggested that the massive stroke suffered by Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon was divine retribution for “dividing God’s land,” ceding Gaza to the Palestinians. He later apologized for the statements.

The comments, and many others, brought strong criticism — and jokes from late-night talk show hosts.

A tendency to shoot from the hip was not new for Robertson, who declared in 1992 that feminism caused women to “leave their husbands, kill their children, practice witchcraft, destroy capitalism and become lesbians.”

He later said such comments were the result of impulsive tendencies. “My passion runs ahead of me ,” he told ABC’s “Good Morning America” in 2006. “The problem is, I ad lib.”

Marion Gordon Robertson was born March 22, 1930, in Lexington, Va., the younger of two sons in a Southern family steeped in politics and religion. He was nicknamed “Pat” by his older brother.

His father, Absalom Willis Robertson, served 34 years in Congress. His mother, the former Gladys Churchill Willis, was deeply religious, and later influenced her younger son to devote his life to God. Both his grandfathers were Baptist clergymen.

After high school at an elite academy in Tennessee, he graduated in 1950 with a bachelor’s degree in history from Virginia’s Washington and Lee University. He studied economics in London before joining the Marine Corps and serving two years during the Korean War, leaving with the rank of lieutenant.

In 1986, as Robertson was mulling a presidential run, former Rep. Pete McCloskey Jr. (R-San Mateo), who served in Korea and knew him there, released a letter saying Robertson had used his father’s influence to avoid combat duty. Robertson sued for libel, but later dropped the suit and agreed to pay McCloskey’s court costs.

In 1955, Robertson earned a law degree from Yale, but failed the bar and never practiced. At Yale, he met Adelia Elmer, a nursing student known as Dede, and they married in 1954. They had four children, Timothy, Elizabeth, Gordon and Ann, all of whom survive him. His wife died in 2022.

It was during a brief business career, while he and his wife were living in New York City, that Robertson first felt what he would call a “God-shaped vacuum” in his life. “I was so burdened with the futility of life that at one point I actually considered suicide,” he wrote in “Shout It From the Housetops,” his 1972 autobiography.

After meeting with a Baptist evangelist sent by his mother, Robertson said he had a born-again experience and rushed home to tell his stunned wife that he had been saved. He enrolled at New York Theological Seminary, earning a master’s degree in divinity in 1959.

Although he was soon an ordained Southern Baptist minister — he resigned when he ran for president — Robertson embraced the charismatic movement, characterized by a personal relationship with God and a belief in faith-healing, prophesy and the ability to speak in tongues.

Through his ministry, Robertson claimed credit for healing illnesses and even diverting natural disasters. In 1986, he said on the air that the previous year, he had “prayed away” Hurricane Gloria, which skipped his home base of Virginia Beach, Va., but slammed into North Carolina and later Long Island.

Robertson often said God gave him personal guidance, including directing him in 1959 to buy the TV station he used to create his religious channel, the nation’s first. He then had the idea of asking 700 viewers to pledge $10 a month to meet the station’s monthly expenses, which became the basis for the “700 Club” show. He was also a pioneer in the use of satellite transmissions to cable television systems.

In 1980, concerned about a lack of wholesome programming elsewhere, he bought the rights to old TV series, including westerns and family-friendly shows such as “Father Knows Best,” which helped expand the Christian Broadcasting Network’s viewership. Its family entertainment arm was eventually spun off and in 1997, sold to Fox Kids for a reported $1.9 billion, and later to Disney.

Among his other enterprises were Regent University, a Christian university in Virginia Beach with graduate programs and an accredited law school, and Operation Blessing, a global charity.

Robertson was edging toward politics by the early 1980s, focusing on national and global issues on “The 700 Club.” “I have always thought that Christians should get involved in public life,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1985.

When he ran for president, he shared much of the agenda of other Republicans seeking the nomination. But, moved by what he saw as the nation’s moral decline, he went beyond what then was the standard conservative line.

He not only called for measures against abortion, but tax breaks for “stable family units,” in which mothers stayed home with their children. He offered ringing endorsements of school prayer, implying it would ease the problems of illiteracy and drug use. And he said landlords should be able to discriminate without criminal penalty against people with AIDS.

With strong donations and dedicated volunteers, Robertson finished second in Iowa’s GOP caucuses to Kansas Sen. Bob Dole, with Bush coming in third. He did well in several other states but poorly in New Hampshire and the Super Tuesday primaries. He withdrew soon afterward, endorsing Bush, who went on to win the presidency.

Armed with a database of thousands of donors and supporters, he founded the Christian Coalition the next year. As the group gained political clout, Robertson was invited to the White House and Capitol Hill. In 1995, he was on the cover of U.S. News & World Report for a story about the power of the religious right.

But the influence of the Christian Coalition — and Robertson — soon began to fade. Reed stepped down in 1997 and the coalition struggled with financial and other problems. In 2001, Robertson resigned too, both as president and from the coalition’s board, saying he wanted to focus on other interests. By then, the organization was in debt.

Robertson continued to appear on “The 700 Club” into his 90s, although his son Gordon, appointed chief executive officer of CBN in 2007, became the program’s primary host. Robertson retired in 2021.

By 2006, after his increasingly provocative statements, old allies and friends in the evangelical movement began to distance themselves. “He speaks for an ever-diminishing number of American evangelicals,” said Richard Land, president of the Southern Evangelical Seminary.

But Robertson was undaunted and continued to speak out, whether it was to blame the destructive nature of storms or hurricanes on the LGBTQ community or to make wild predictions, such as his forecast that asteroids would soon destroy Earth. He cheered Donald Trump’s election but later said he found the president “very erratic” and someone who “lives in an alternate reality.”

Some analysts suggested Robertson was simply dialing up his rhetoric in an attempt to reclaim his position as the face of the religious right.

“As his influence waned and the movement diversified,” Olson said, “maybe he was trying to insert himself back into a position of relevance.”

Trounson is a former Times staff writer.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.