Mike Reynolds, father of California’s ‘three strikes’ law, dies at 79

- Share via

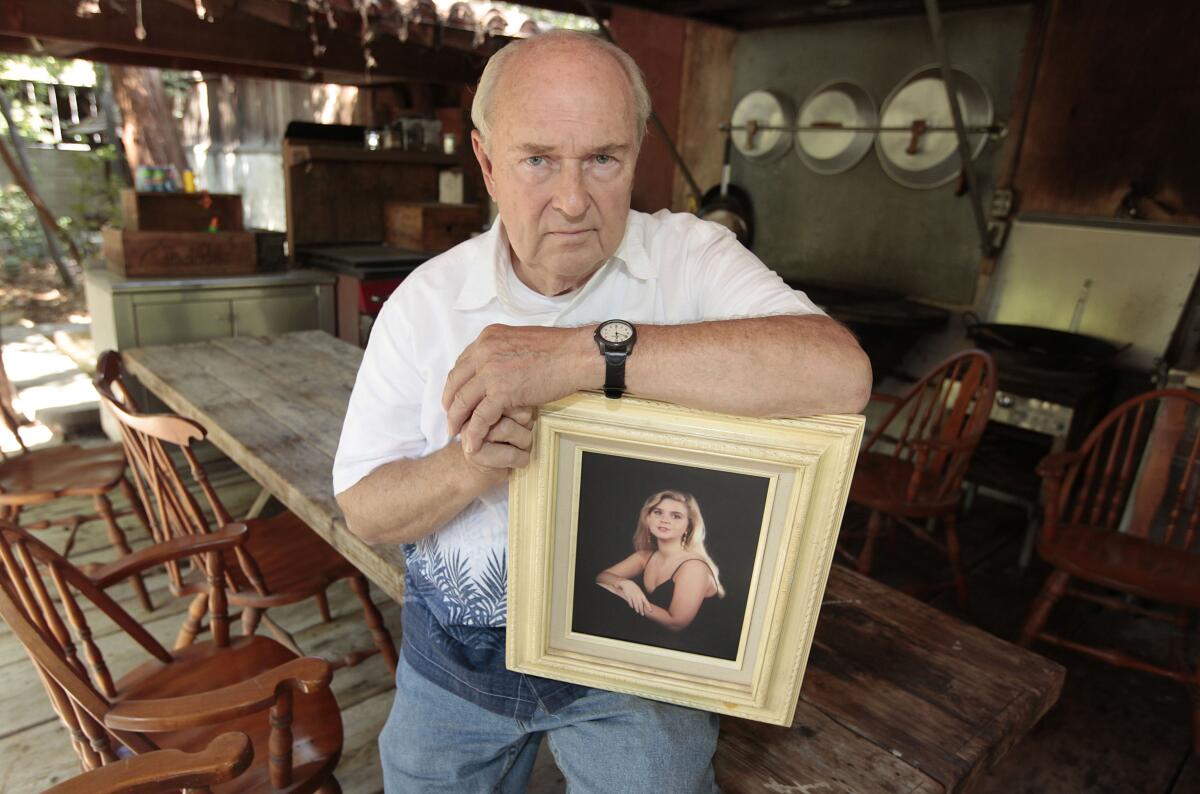

Mike Reynolds, whose grief-driven crusade to get tough on criminals after his daughter’s murder led to the passage of California’s “three strikes” law, has died. He was 79.

After Reynolds’ unlikely three-strikes victory in 1994, the tide in California eventually turned, as reformers implemented new legislation and successfully rolled back measures they blamed for disproportionately incarcerating people of color.

Through the years, Reynolds remained at the forefront of the victims’ rights movement, insisting that not an inch should be ceded to criminals.

“Once someone has had two serious or violent convictions, the question is, who do we give the next chance to? I vote in favor of the next victim,” he wrote in The Times in 1999.

Reynolds had open heart surgery in May and struggled to recover; he died from complications of the surgery on Sunday, said his son, Michael Reynolds.

Reynolds’ quiet life as a wedding photographer in Fresno was upended in June 1992 when his 18-year-old daughter, Kimber Reynolds, was ambushed by two parolees who tried to steal her purse. One of them fatally shot her in the head after she fought back.

It was the summer of 1992, a few days after Mike and Sharon Reynolds had laid their only daughter, Kimber, to rest after she had been fatally shot by a parolee who tried to steal her purse.

Kimber’s killer, who was a career criminal and would have still been behind bars under three-strikes, died in a shootout with police. His accomplice was sentenced to nine years in prison and released on parole after about four.

Days after Kimber’s funeral, Reynolds met with then-Gov. Pete Wilson and told him, “I’m going after these guys in a big way, the kind of people who would murder little girls in this way.”

He did just that, turning his grief into policy at a picnic table he built in his backyard. Over barbecue he cooked in his outdoor kitchen, Reynolds brainstormed statutes with state representatives, judges and attorneys. He frequently appeared on radio talk shows, sharing Kimber’s story.

At that picnic table, Reynolds came up with the idea of imprisoning habitual felons for much longer terms. After running into opposition in the state Legislature, he pursued a ballot initiative to put the proposal before voters.

Then, a 12-year-old Petaluma girl, Polly Klaas, was kidnapped and later found dead. The extraordinary publicity surrounding the case rallied public anger about crime. The Legislature enacted a three-strikes bill, modeled after Reynolds’ idea, that imposed mandatory sentences of 25 years to life for a felon with two prior violent crime convictions — even if the “third strike” was a nonviolent crime such as a residential burglary or a drug offense.

It was one of the strictest sentencing laws in the country, and critics immediately lamented the harsh punishments and the immense cost of building prisons for all the offenders sentenced to lengthy terms.

Reynolds pushed ahead, advocating for a bill mitigating the effect of a state Supreme Court decision that gave judges more discretion in applying the three-strikes law.

In 1997, Reynolds helped pass “10-20-life,” also known as “use a gun, and you’re done,” dramatically increasing prison sentences for felons who carry or use guns.

“In the best way, Mike Reynolds was politically awkward. He was not polished,” said former California Atty. Gen. Dan Lungren, a Republican who was an ally on criminal justice issues. “He was like your next-door neighbor coming over and sharing his grief with you. And that made it very real to people. Everyone could relate to that.”

Don Novey, former president of the California Correctional Peace Officers Assn., worked closely with Reynolds for decades on tough-on-crime measures. The two exchanged emails the night before Reynolds died.

“Mike Reynolds struck a chord with the public, and it was at the right time. He matched the mettle of the moment,” Novey said. “There was a transformation in public safety as a result of this man standing tall.”

Many Californians came to view the three-strikes law as too harsh. In 2012, despite Reynolds’ crusading, voters passed Proposition 36, which addressed the law’s most criticized aspect — that someone could receive 25 years to life for a third offense as trivial as stealing a pizza. About 2,800 prisoners with relatively minor third strikes became eligible for reduced sentences.

Well into his 70s, Reynolds continued fighting for tougher penalties for criminal offenders, even as he saw his legacy being dismantled. In 2021, he backed campaigns to recall Gov. Gavin Newsom and other reform-minded politicians and district attorneys. Twenty-nine years later, he and his wife still slept with Kimber’s teddy bear every night.

Traditional crime victims groups are emboldened by the possible recall of Gov. Gavin Newsom and some district attorneys. But other groups are redefining the term ‘victim.’

Mike Reynolds was born in Fresno on Feb. 29, 1944. Working as a photographer for 45 years, he shot more than 4,000 weddings.

When he wasn’t advocating for crime victims, Reynolds enjoyed salvaging old materials and machines.

“He was constantly determined to improve whatever he touched, whether that be the criminal justice system or his spaghetti sauce recipe,” Michael Reynolds said.

Reynolds treasured trips to the family vacation home at Shaver Lake. His sons remember summer parties their father hosted. He was a “messy” though “fabulous” chef who charmed guests with his favorite cuisine, Japanese, and his self-deprecating jokes.

In addition to his son Michael, Reynolds is survived by his wife, Sharon Reynolds; another son, Christopher Reynolds; and four grandchildren.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.