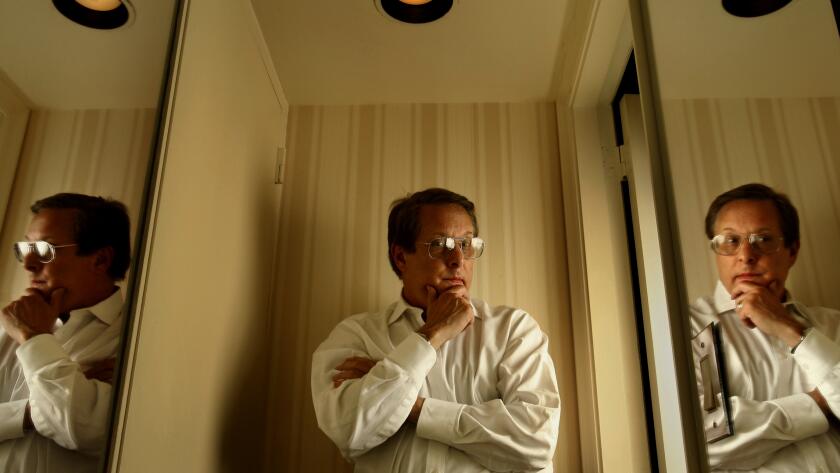

William Friedkin, director of ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The French Connection,’ dies at 87

- Share via

Oscar-winning director William Friedkin, known for ‘The Exorcist’ and ‘The French Connection,’ has died. He was 87.

- Share via

William Friedkin, a master of suspense and leading figure of the 1970s New Hollywood movement who was known for directing films such as “The Exorcist” and “The French Connection,” has died.

Friedkin died Monday in Los Angeles, his widow, Sherry Lansing, confirmed to the Los Angeles Times. CAA, which represents Lansing, said Friedkin died at home from heart failure and pneumonia. He was 87.

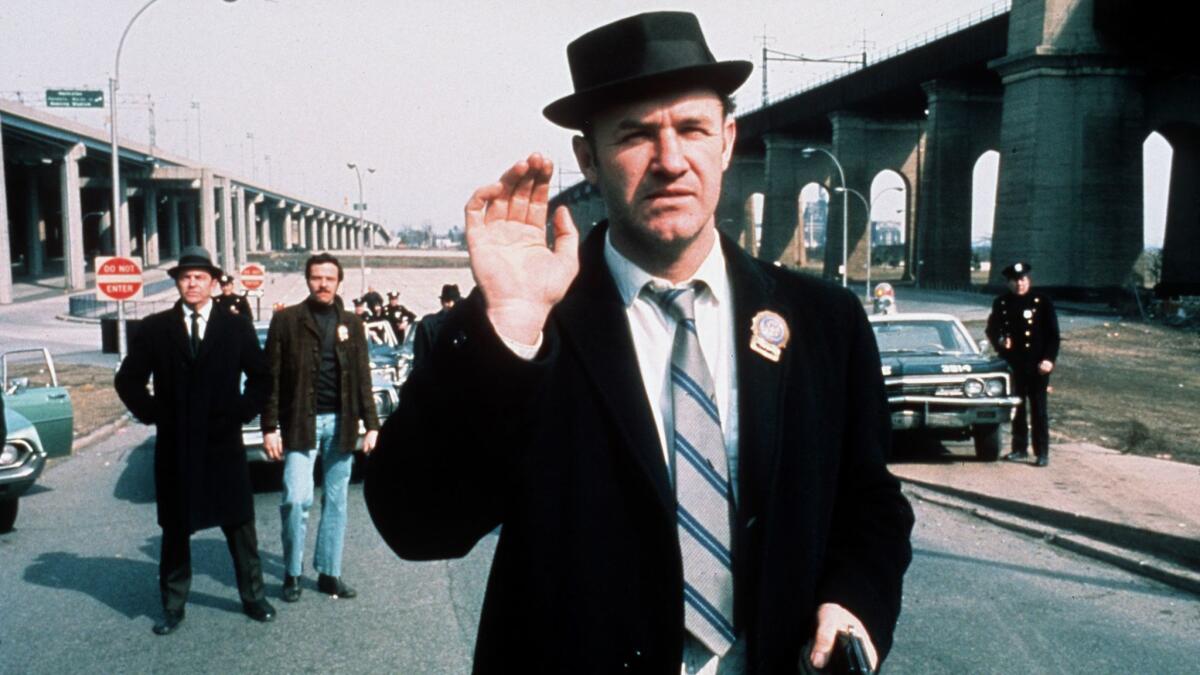

Widely respected as a filmmaker, Friedkin was known for keeping audiences on the edge of their seats with scream-inducing horror classics and fast-moving crime dramas such as “The French Connection.” The film, which starred Gene Hackman and Roy Scheider, took home five Oscars in 1972 — including acting and directing trophies for Hackman and Friedkin, respectively, as well as best picture.

Another smash with audiences and critics alike was “The Exorcist,” which grossed nearly $200 million in 1973 and scored 10 Oscar nominations, including another directing nod for Friedkin. It ended up winning two and still maintains a significant cult following today, spurring spinoffs, sequels and an upcoming reboot trilogy.

Despite his successes, Friedkin — who had been experiencing heart issues for some time before his death — never aimed to be one of the greats.

“I love the experience of making films,” Friedkin told The Times in 1989. “I love the mud. I love the dirt. I love all the inconveniences. That’s why you do it. If you do it because you’re looking to be the Great American filmmaker, you’re liable to experience disappointment. I have never experienced disappointment on any of my films because they all have great memories for me, even some of those that have done less well than others.”

Friedkin began his entertainment career in the 1950s in the mailroom at Chicago TV station WGN, where he quickly climbed the company ladder. During his first eight years in TV, Friedkin directed about 2,000 live shows.

He also was known for his documentaries, including the 1962 TV movie “The People vs. Paul Crump,” which spotlighted a man on death row who Friedkin suspected might be innocent.

The director finally hit the big screen in the late ’60s. He followed up his first feature, “Good Times,” starring Sonny and Cher, with projects such as the showbiz comedy “The Night They Raided Minsky’s” and the groundbreaking drama “The Boys in the Band” — adapted from Mart Crowley’s long-running stage production.

But he didn’t receive Oscar recognition until 1971’s “The French Connection,” which featured scandalous crimes, a pair of hardboiled buddy cops and a famous car chase through the tough streets of New York City.

“I’m fascinated by criminal behavior,” Friedkin said in a 1985 interview. “Discovering what it is that pushes some people over the line. Some directors call their agents to find out the grosses; me, I call friends in law enforcement to find the truth behind the crimes.”

In addition to its academy accolades, the film also scored three Golden Globes, including best picture and director. And Friedkin would have another fruitful awards season two years later with “The Exorcist,” which made history as the first horror film to clinch a best picture Oscar nomination and once held the title for the highest-grossing film of all time. He also won a Golden Globe for directing the film.

“On the set, he knew what he wanted, would go to any length to get it and was able to let it go if he saw something better happening,” “Exorcist” star Ellen Burstyn said Monday in a statement. “He was undoubtedly a genius.”

William Peter Blatty, who wrote the screenplay for the blockbuster, as well as the novel on which it’s based, praised Friedkin in a 1974 interview for his handling of the story, saying he’d “never worked with a more conscientious director.” And Jason Miller, who played the ill-fated priest who performs the exorcism, credited the director with kick-starting his career by taking a chance on an unknown actor.

“The eight months I worked with Billy was probably the most productive period of my life,” Miller said. “He respects actors. He gives them the freedom to build a character. A lot of directors say, ‘Walk over here, look at the grass and pick up the line.’ Billy lets you create.”

“When it comes to directorial influence, Billy was a titan — both on the screen and behind the scenes for his fellow members of the DGA,” Directors Guild of America President Lesli Linka Glatter said Monday in a statement, adding that Friedkin “never kept his talent to himself.” He served several terms on the guild’s National Board and volunteered over the years for myriad DGA seminars, panels and events.

Friedkin continued to follow his passion for crime and tortured characters later in his career with projects such as the critically acclaimed 1985 thriller “To Live and Die in L.A.,” starring William Petersen and Willem Dafoe. On all of his films, Friedkin was notorious for his focused, often dark directorial vision — which sometimes led to disagreements on set with cast members, such as Dafoe.

“I do get annoyed when you are told to be aggressive or sadistic when the character isn’t always required to be,” the actor said in 1985, referencing his experience working with Friedkin. “I’d suggest a lighter touch, and Billy would say, ‘It’s inappropriate.’ And as I watched the film, there were times when I thought it was stronger than I’d intended playing it, and that kind of made me sick.”

But conflicted characters were the ones Friedkin said he liked best. The director often fielded questions about his seeming affinity for sinister and corrupt personalities.

“I’m interested in people who live without alternatives, whose backs are to the wall,” Friedkin said. “What unites all my films ... is that they all involve people living on the edge of very intense situations that are forcing them into irrational behavior and a kind of last-chance reaction to life. I guess it’s because I find that situation in my own personal life very often.”

In 1991, Friedkin married Lansing, the first woman to serve as the head of a major Hollywood studio. They would remain together for 32 years, until his death. He was previously wed to actor Jeanne Moreau from 1977 to 1979, actor Lesley-Anne Down from 1982 to 1985 and news anchor Kelly Lange from 1987 to 1990.

Friedkin went on to explore moral quandaries and supernatural phenomena with projects such as “Bug,” “Killer Joe” and another exorcist-centric film, “The Devil and Father Amorth.” He also returned to his roots in TV, picking up a directing Emmy nomination for his 1997 adaptation of “12 Angry Men.”

Friedkin’s final feature — “The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial,” starring Kiefer Sutherland, Jason Clarke, Jake Lacy, Monica Raymund and Lance Reddick — is slated to premiere at the 2023 Venice Film Festival.

“Working with William Friedkin was one of the great honors of my career,” Sutherland said Monday in a statement. “My condolences go to Sherry and his family.”

After much success on the screen, the director eventually turned his talents to the stage, helming multiple operas including “Wozzeck,” “Duke Bluebeard’s Castle,” “Ariadne auf Naxos” and Richard Strauss’ “Salome.”

Friedkin was born in Chicago on Aug. 29, 1935, and raised in a close-knit family. His mother was a nurse and his father a merchant seaman and semi-pro baseball player. Though he was a star basketball player in high school, he drifted toward entertainment instead, working at WGN-TV, eventually as a director.

He moved to Hollywood in 1965 after winning an award at the San Francisco International Film Festival and directed one of the final episodes of “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour.” Hitchcock reportedly admonished him for not wearing a tie to work.

“There’s no reason why I should be a filmmaker,” Friedkin told The Times in 2012. “I never studied film, I never went to college. I just got into film because at that time my own interests coincided with that of the general public and the audience and I was young. I managed to hang on out of equal parts ambition, luck and the grace of God.”

Friedkin is survived by Lansing and two sons, Cedric and Jackson. They intend to hold a private service.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.