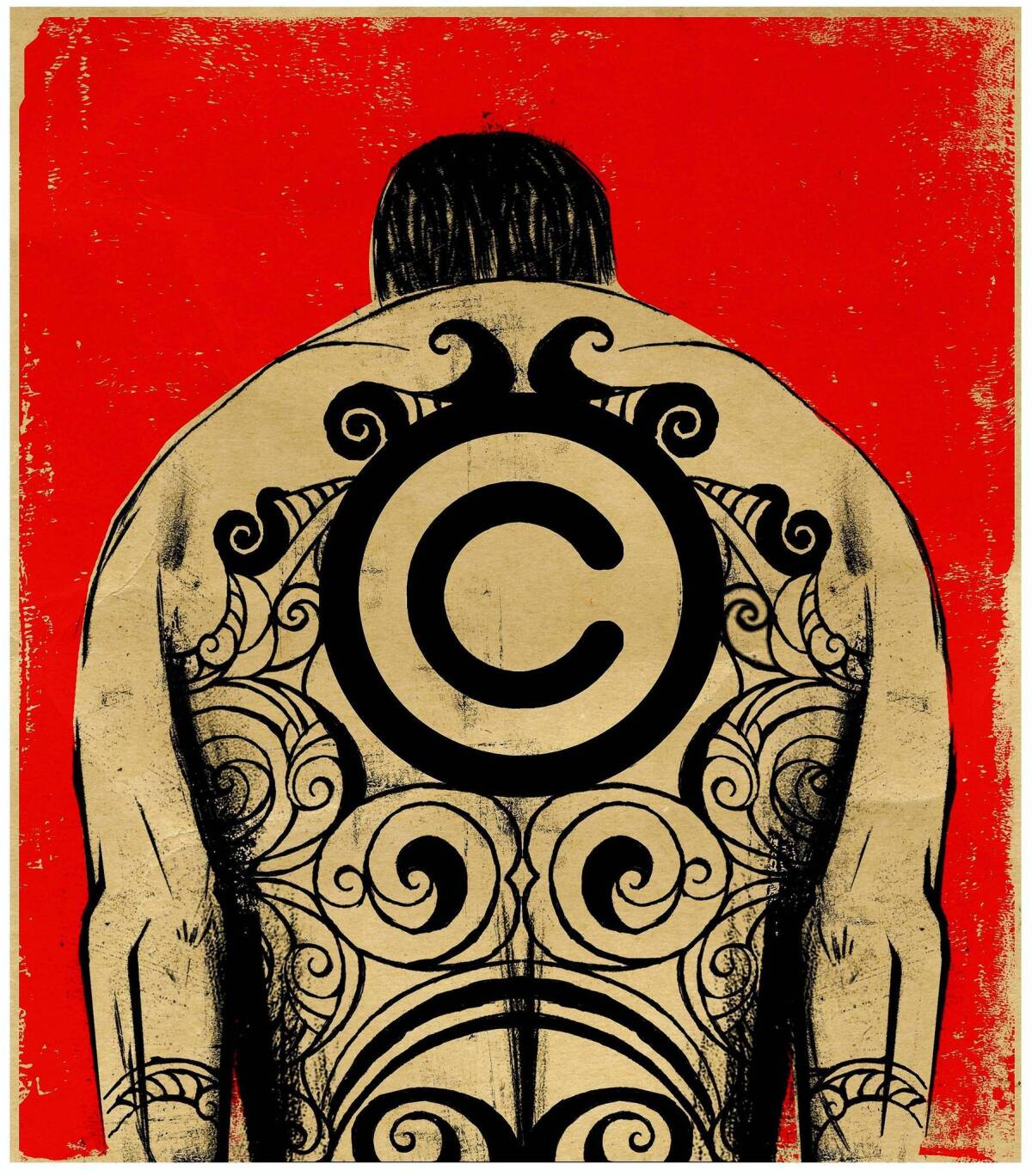

Whose tattoo is it anyway?

- Share via

Who owns a tattoo? The obvious answer is the wearer, who paid for the ink and is now permanently (more or less) attached to it. Yet recent disputes have called into question the easy idea that if you buy a tattoo, you also own it and can display it as you like. Tattoo artists are increasingly claiming that they, like other artists, own the copyright to the images they create. And when those images, attached to living people, appear on the silver screen — or a computer monitor — the artists want to get paid.

Late last year, for example, Stephen Allen, a tattoo artist, sued video game maker Electronic Arts and former Miami Dolphins running back Ricky Williams over a tattoo Allen put on Williams’ bicep. The tattoo appeared on the cover of EA’s “NFL Street” video game. Allen claimed that the reproduction and display of the tattoo violated his copyright.

That case was dismissed in April at the request of the plaintiff, but because so many NFL players have tattoos, it got the attention of the NFL Players Assn. NFLPA officials began advising players to get copyright waivers from their tattoo artists. George Atallah, an NFLPA official, told Bloomberg Businessweek that the union recently cautioned its players: We know you love your tattoo artists, but regardless of whether you trust them, regardless of whether there are legal merits to the lawsuits that we’ve seen, just protect yourself.

Allen’s was not the first lawsuit. Others include a 2011 case brought by tattoo artist Victor Whitmill against Warner Bros. The suit was filed just weeks before the release of the hit film “The Hangover: Part II.” In the film, comedian Ed Helms wakes up with a copy of boxer Mike Tyson’s famous Maori-inspired facial tattoo. Whitmill claimed that Warner Bros. owed him for re-creating the Tyson tattoo. The case was settled for an undisclosed sum.

At one level, the idea that one person owns an integral part of another person’s body seems hard to fathom. But as tattoos move ever more into the mainstream — more than one-third of Americans younger than 40 now have one — the issue is hardly as arcane as it may first appear.

Yet there’s little doubt that tattoos are copyrightable under American law. In our intellectual property system, all that’s required is that they be minimally creative, “fixed in a tangible medium of expression” (which simply means written down in some way) and persist for more than a “transitory duration.” Given how hard tattoos are to remove, and that ink on skin is little different than ink on paper, tattoos clearly fit the bill.

But if there’s little doubt that tattoo artists are entitled to copyright, it is far from clear what rights that should give them over their creations. Ordinarily, copyright owners have the exclusive right to authorize public displays of their work. This means that an artist can, for example, sell a painting to a collector, but for the artwork to appear in a film, the artist must either approve or have explicitly sold that right to the collector.

In the case of a tattoo, does that mean that the tattoo artist copyright owner has the right to order his client to stay indoors — or off the movie set? Surely not. That would be a denial of the client’s personal freedom, and no court would or should allow it. But short of that, how much control should copyright law give a tattoo artist over the person whose skin bears the artist’s work?

The best way to answer that question is for courts to establish a rule for what lawyers call an “implied license.” This would mean that, in the absence of a written contract providing otherwise, the tattoo artist waives any right to control public display or commercialization of the tattoo as it appears on the client’s body. Such a rule is fair for two reasons.

First, tattoos are the only form of art that is indelibly fixed on a human body. To give a tattoo artist control over how the tattoo may appear in a film or other work inevitably means giving that artist some control over the body that bears it. Copyright law was never meant to give anyone control over someone’s freedom to move about in public, to have their picture taken or to commercialize their likeness.

Second, the law should reflect what both inker and inked reasonably expect when the tattoo is purchased. Copyright disputes over tattoos will almost always involve celebrities. When a tattoo artist works on a public figure, whether an athlete or actor, he knows that his art will be going public as well. And of course the artist is free to demand a higher price for a tattoo that will get wide notice. There’s no guarantee, of course, that the artist will get it or even ask for it — having a tattoo displayed prominently on a popular athlete’s or movie star’s body is a great career-builder.

But the point is that when a tattoo artist works on a celebrity, everyone expects that the tattoo will be displayed publicly, and that the celebrity may profit from images that include the tattoo. The artist and his client can certainly agree otherwise in a written contract.

Absent such an explicit agreement, the legal rule should align with what everyone expects: that people with tattoos will move around, appear in public and maybe star in a video game. Copyright law should not provide a way for tattoo artists to restrain the freedom of their clients.

Kal Raustiala and Christopher Sprigman are law professors at UCLA and NYU, respectively, and the coauthors of “The Knockoff Economy: How Imitation Sparks Innovation.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.