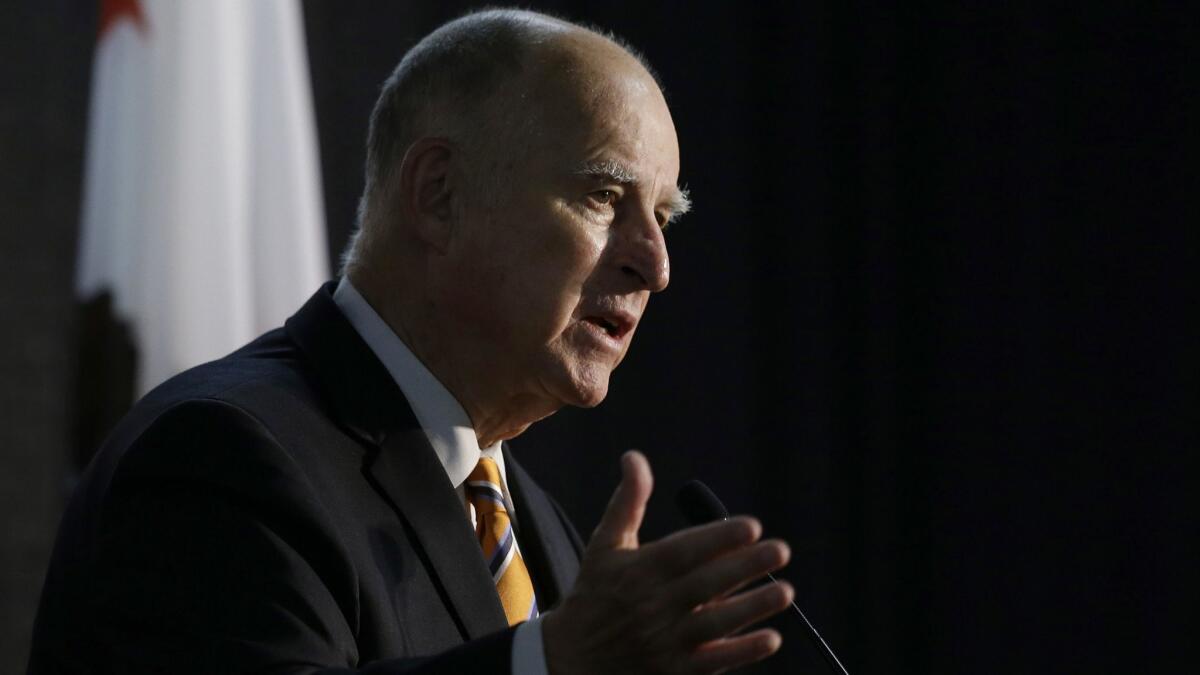

Editorial: Jerry Brown launched the era of police secrecy. Forty years later, he is partially correcting that mistake

- Share via

Gov. Jerry Brown launched an era of police secrecy in 1978 when he signed a bill to prohibit the public release of information about officer misconduct and excessive uses of force. He partially corrected that mistake on Sunday with his signature on SB 1421, a bill that will once again — after a lapse of 40 years — require law enforcement agencies to disclose some essential information about their officers. Californians should both rejoice in the change in the law and be chastened by how long it was in coming.

It’s mind-boggling that for all those years, prosecutors who wanted to put officers on the stand have not been allowed to check their records for patterns of dishonesty. Nor has the general public been able to learn which officers account for disproportionate injuries, deaths and public liability.

That lack of accountability for police can’t be what Brown had in mind four decades ago. And in fact the 1978 bill he signed wasn’t a total blackout on information. But courts increasingly interpreted the law in ways that minimized disclosure.

It was once common for the public to learn of officer misconduct when police appealed disciplinary actions to administrative bodies and police commissions, which conducted their hearings in public. But even that crucial degree of disclosure was cut off in 2006, when the state Supreme Court ruled that personnel records may not be openly discussed in administrative appeal hearings.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

Only a precious few lawmakers pushed bills to reinstate public disclosure of basic information, and their efforts failed under the pressure of powerful police unions. Until now.

SB 1421 went the distance in part because it is so modest. It does not provide public access to complaints against officers, as some of the previous bills would have done. It does not require release of information about every use of force.

But it does require disclosure, under the Public Records Act, of every report of an officer discharging a firearm and every use of force that results in death or great bodily injury. It grants public access to information about officer on-duty sexual assaults against members of the public (or exchanges of leniency or other favors for sex) and dishonesty in police reports, investigations and prosecutions.

Much of Brown’s work on policing and criminal justice in his second eight-year run as governor has responded to or corrected well-meaning work in his first stint that over time was misused, or became outdated, or was just proven wrong-headed.

We should resist any temptation to see his signature Sunday as the final corrective that restores the proper balance on police accountability. There is plenty of work yet to be done. But it will fall to more typical governors — those without the exceedingly rare perspective, and wisdom, granted by two tenures spaced so far apart in time.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.