Editorial: Should people on the no-fly list be able to buy guns? Yes.

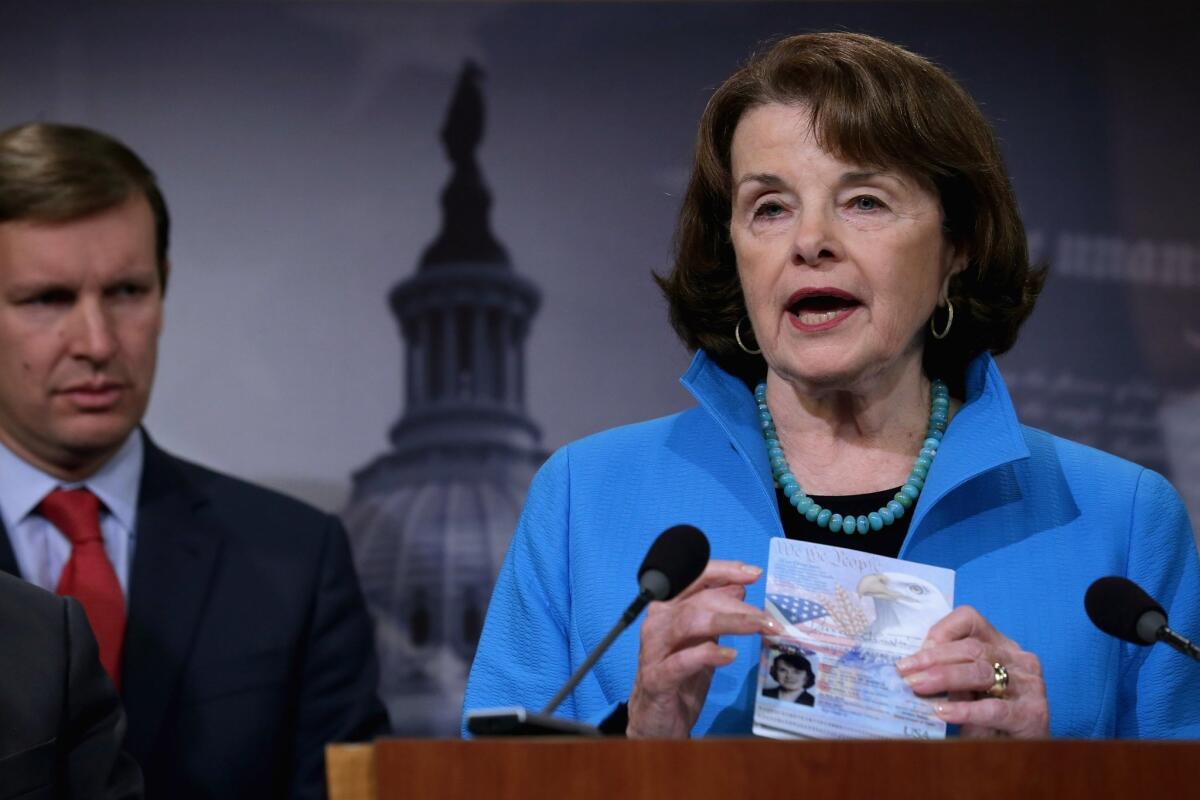

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) holds up her passport last month during a news conference about Democratic legislative proposals to combat terrorism.

- Share via

It seems simple enough: If the federal government, based on intelligence or policing, puts a person on its watch list of suspected terrorists or decrees that he or she is too dangerous to be allowed on an airplane, then surely it would also be foolish to let that person buy a firearm in the United States. Makes sense, doesn’t it?

That was the thrust of a proposed law by Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) that her Senate colleagues rejected last week amid much political furor. The idea was resuscitated by President Obama in his Oval Office address Sunday evening. “What could possibly be the argument for allowing a terrorist suspect to buy a semiautomatic weapon?” the president asked.

When he puts it that way, it does sound pretty stupid. But, in fact, there are several strong arguments against the proposal.

Ending gun violence is critically important, but so is protecting basic civil liberties.

One problem is that the people on the no-fly list (as well as the broader terror watch list from which it is drawn) have not been convicted of doing anything wrong. They are merely suspected of having terror connections. And the United States doesn’t generally punish or penalize people unless and until they have been charged and convicted of a crime. In this case, the government would be infringing on a right guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution — and yes, like it or not, the right to buy a gun is a constitutional right according to the U.S. Supreme Court.

How certain is it that the people on the two lists are dangerous? Well, we don’t really know, because the no-fly-list and the broader watch list are government secrets. People are not notified when they are put on, nor why, and they usually don’t discover they have been branded suspected terrorists until they try to travel somewhere.

But serious flaws in the list have been identified. According to the American Civil Liberties Union, which is suing the government over the no-fly list, the two lists include thousands of names that have been added in error, as well as the names of family members of suspected terrorists. The no-fly list has also been used to deny boarding passes to people who only share a name with a suspected terrorist. Former Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) was famously questioned at airports in 2004 because a terror suspect had used the alias “T. Kennedy.” It took the senator’s office three weeks to get his name cleared.

FULL COVERAGE: San Bernardino terror attack | Live updates

What’s more, it’s not clear how much impact Feinstein’s law would have. The broader watch list, which is actually a database maintained by the FBI’s Terrorist Screening Center, apparently had about 480,000 names on it in 2011, according to the FBI, and it has since swelled to about 1.1 million names, according to the ACLU. Of those, the vast majority are noncitizens living overseas; the number of American citizens on the list is believed to be fewer than 10,000 people.

That’s important because federal law already bars gun sales to most people who are not U.S. citizens or lawful permanent residents or holders of valid visas, which means the vast majority of the people on the suspected terror list would already be barred from buying a firearm in the U.S. even without Feinstein’s law. That leaves us with about 10,000 American citizens (and some legal residents) who, under the proposed law, would be barred from exercising a constitutional right. That gives us pause.

Truthfully, no one should be allowed to buy assault rifles or other military-style firearms, and the country would be better off with much stronger gun control laws for other firearms than exist now. What’s more, this page disagrees with the Supreme Court’s 2008 ruling that the 2nd Amendment guarantees an individual the right to own a gun. But that is a recognized right, and we find it dangerous ground to let the government restrict the exercise of a right based on mere suspicion.

Feinstein’s proposal contained some worthy safeguards. Before a person could be denied the right to purchase a gun, the Justice Department would have to have a “reasonable suspicion” that the weapon would be used in connection with terrorism. But that would work much better if there was a judge — an unbiased third party — to review the affirmation and deem it valid, as is done in issuing search warrants. Also under Feinstein’s bill, if a person were denied a gun sale because his or her name was on the terror list, the person would have to be informed and could challenge the decision. That’s good, but also insufficient. If the government wants to use its watch list to vet gun sales, it ought to present credible evidence to a presumably unbiased judge.

It is worth noting that the terrorist-list proposal would not have affected the San Bernardino attackers because neither of them was on the watch list, at least as far as has been reported. And although backers of the measure cite Government Accountability Office data that show more than 2,000 people on the list bought firearms from 2004 to 2014, there’s no available information on whether any of those weapons have been used in a crime, let alone an act of terrorism.

Ending gun violence is critically important, but so is protecting basic civil liberties. Although we agree to the ends here, we object to the means.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

MORE FROM OPINION

Trump’s latest howler on Muslims isn’t funny; it’s poisonous

Obama said the right things about terrorism, but he waited too long to say them

Gun and self-defense statistics that might surprise you -- and the NRA

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.