Op-Ed: Inside the minds of America’s presidential assassins

- Share via

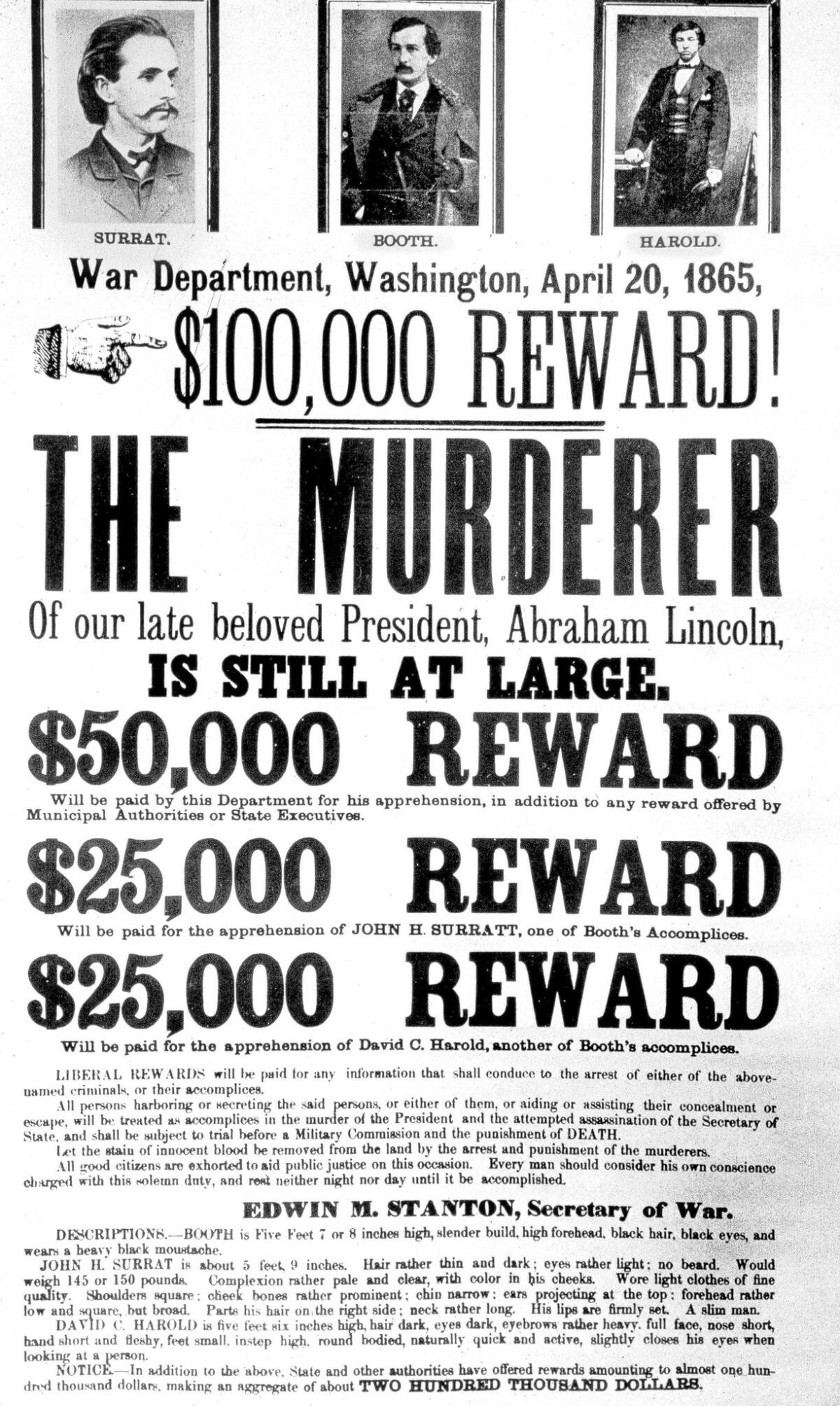

On the evening of April 14, 1865, by some accounts, John Wilkes Booth stopped in at a tavern on his way to Ford’s Theatre in Washington. A man at the bar, recognizing the actor, noted that Booth wasn’t as fine a thespian as his father had been. “When I leave the stage,” Booth is said to have retorted, “I’ll be the most famous man in America.”

Less than an hour later, he shot and killed Abraham Lincoln.

Booth’s desire for fame and recognition is a common theme among assassins. In researching a book on presidential killers and would-be killers, I found that they tended to share certain personality traits. While some had been treated for mental illness, an even more predominant characteristic is that many of them were disillusioned with and resentful of American society after a lifetime of failure. And most of them also had a burning desire for notoriety. Killing an American president, most would-be assassins believed, would win them a place in history, making a “somebody” out of a “nobody.”

Four American presidents — Lincoln, James Garfield, William McKinley and John F. Kennedy — have been assassinated. One other — Ronald Reagan — was wounded in an assassination attempt. There have also been at least 10 other attempts in which armed presidential stalkers have been prevented from carrying out their plans, as well as numerous plots that were either foiled by law enforcement or abandoned by the would-be assassins.

By my estimate, there have been at least 32 definite and well-planned but never-executed plots against presidents that were judged to be serious by the Secret Service.

So, who were these plotters? Garfield’s assassin, Charles Guiteau, was an erratic lawyer and itinerant preacher who had failed at everything he tried, including trying to get a job in the Garfield administration. McKinley’s assassin, Leon Czolgosz, had suffered a mental breakdown and despaired of his lowly position in life. He sometimes used the alias Fred C. Nieman — literally, “Fred Nobody.”

Both JFK’s assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, and Robert Kennedy’s assassin, Sirhan Sirhan, (who wanted to kill President Lyndon Johnson) had held jobs they considered beneath them. Oswald’s wife, Marina, said her husband believed himself to be “an outstanding man” and resented not being recognized as such.

Sirhan was resentful of the wealthy and successful and embittered over U.S. support for Israel.

Samuel Byck, who killed a pilot as he attempted to hijack a Delta Air Lines jetliner, intended to crash the plane into the White House to kill President Nixon. He was a social and business failure who blamed the government for not giving him a small-business loan.

Disgruntled busboy Arthur Bremer stalked Nixon before he shot and paralyzed presidential candidate George Wallace. “Life has been only an enemy to me,” he wrote in his diary.

One reason it’s so hard to prevent assassination plots is that, to the people who hatch them, the infamy they achieve is worth whatever price they might have to pay. As Sirhan put it: “They can gas me, but I am famous. I have achieved in one day what it took Robert Kennedy all his life to do.”

Mark Chapman, who killed former Beatle John Lennon in December 1980, had also considered targeting Reagan. “I was an acute nobody,” he told authorities after his arrest. “I had to usurp someone else’s importance, someone else’s success. I was ‘Mr Nobody’ until I killed the biggest somebody on Earth.”

Giuseppe Zangara, would-be assassin of President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt (he shot and killed Chicago Mayor Anton Cermak in the attack), went stoically to the electric chair after he was convicted, losing his composure only when he discovered there were no photographers present to witness his execution.

In the days leading up to his assassinating Garfield, Guiteau was excited about the prospect of the attention he would receive. As he explained it in a jailhouse interview with the district attorney, later published in the New York Herald, “I thought ... what a tremendous excitement it would create, and I kept thinking about it all the week.”

Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated. But the motivations that drove his assassin were unfortunately not unique. Understanding the nature of those who want to kill a president goes considerably further toward explaining assassinations than looking to fanciful conspiracy theories.

Mel Ayton is the author of the new book “Hunting the President: Threats, Plots and Assassination Attempts — From FDR to Obama.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.