Op-Ed: ‘Yellowface’ in ‘The Nutcracker’ isn’t a benign ballet tradition, it’s racist stereotyping

- Share via

“The Nutcracker,” on stage somewhere near you during the holiday season, counts among its second act “Land of the Sweets” dances a perky flute-saturated Tchaikovsky variation properly called “Tea” but better known as “Chinese.” For years, various versions have either trafficked in sad Asian stereotypes, or, occasionally, presented athletic romps with vague references to actual Chinese culture — fans, conical straw hats and mandarin-collared costumes.

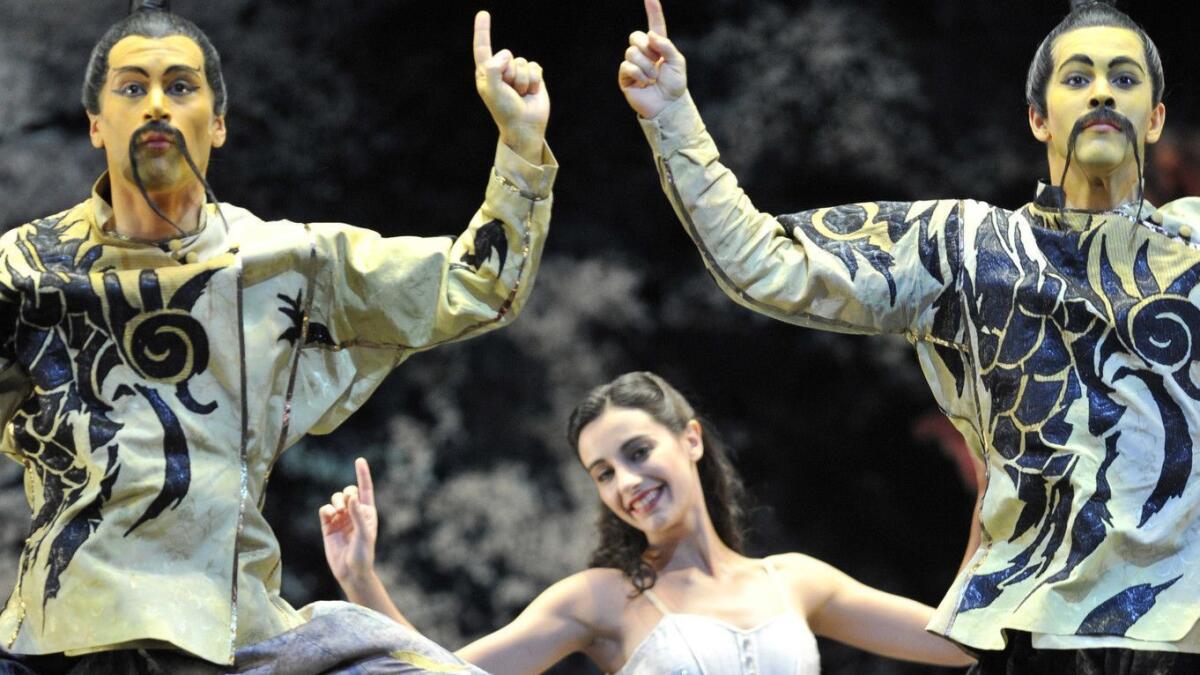

One of the most common of the ballet world’s efforts to signal Chinese-ness is a particular hand gesture — a sort of two-finger salute with the index digits of each hand stretched out to opposite sides like a peripheral vision test. Any “Nutcracker” aficionado will recognize it as “Chinese,” but as a dance scholar, I can tell you the gesture does not exist in any version of traditional dance in China.

Is the two-finger salute quaintly naïve? Or offensive? I’ve discovered it might have evolved as an imitation of a traditional Mongolian chopstick dance, using a single finger to stand in for the chopsticks. But that derivation can’t save it. The finger-pointing is mostly an example of heedless insensitivity to stereotyping.

Now — finally — it seems time’s up for ballet’s biased portrayals.

But of course, it’s hardly the worst embodiment of racism on the ballet stage. Blackface is still tolerated in some “traditional” Russian ballets, and “The Nutcracker’s” Arabian Dance in Act 2 could also use an overhaul. In a long career of dancing, studying and writing about “The Nutcracker,” I’ve cringed over the Chinese Dance’s bobbing, subservient “kowtow” steps, Fu Manchu mustaches and, especially, the often-used saffron-tinged makeup, widely known as “yellowface.”

Ballet people will argue that all of these elements in “The Nutcracker” are just tradition, that no insult is intended. But in 2018, no one should be able to plead ignorance of stereotyping’s dangers. During my “Nutcracker” research in dozens of backstage conversations, I ran into effervescent young ballet girls, most of them white, who dutifully told me that the Chinese Dance helped them “learn about other cultures.” What I saw them learning was how to flatten anyone of Asian descent into a cartoon.

Now — finally — it seems time’s up for ballet’s biased portrayals. Last year, New York City Ballet soloist Georgina Pazcoguin (who is part Filipino) and former dancer Phil Chan created a “Final Bow for Yellowface” pledge for dancers. They laid out the problems with some Chinese Dance portrayals on a website, with helpful history and strategies about how to replace offense with respect, without losing the dance or its Chinese connection.

The New York City Ballet got the message. Founding choreographer George Balanchine originally gave NYCB’s Chinese Dance mostly energetic, inoffensive steps, but as of 2017, some shuffling and pointy fingers were eliminated, as well as geisha wigs and exaggerated makeup. (As Pazcoguin and Chan note, the Chinese Dance is the only “Nutcracker” variation in which dancers are made up to look like a member of a race other than their own).

In keeping with other somewhat slow moving but ineluctable “aha” moments, other ballet companies have been coming around. My former company, the Louisville Ballet, I’m happy to say, signed the pledge against yellowface, but they had in fact already replaced a 2009 staging that had made me wince. It featured a cartoon Mandarin “comically” depriving his timid female servants of a drop of tea.

San Francisco Ballet was also in the vanguard. It has for years featured a dragon dance as its Chinese Dance, based in its Chinatown traditions. Other companies where I’ve done research are jettisoning the pointy fingers and excessive bowing, sticking to Chinese fans and fabrics that seemed a benign homage, even echoing the spirit of some Chinese opera characters.

I got a chance to do a little more digging about the two-finger gesture when I taught ballet history to dance teachers at the Beijing Dance Academy last year. We watched many versions of the “Nutcracker” Chinese Dance available on YouTube. They pronounced one version “most authentic” because it copied costumes of a specific era accurately. But what I saw in it was choreography filled with egregious bowing and other “Chinese” silliness. They weren’t offended, I realized, because there was little reason for them to recognize injurious stereotyping by Westerners. They had never suffered from it, and they had little knowledge of the long history of insulting race-based caricatures in the U.S.

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

What did they think about the two-finger salute? They were perplexed at first, what did it mean? I explained it might stand in for chopsticks. Oh, a few teachers said, maybe that was OK. But one veteran ballet instructor crossed his arms, his face screwed up with suspicion as he thought about it.

“Yeah…” he said, through a translator. “I don’t like that.”

He couldn’t quite explain why he doubted the innocence of the gesture, but he was surely right to do so. It was a remnant of outsider dismissiveness, a gesture made worse because it is made to stand in for all of Chinese identity. Now, those ballet fingers are at last pointing toward change.

Jennifer Fisher is a professor at UC Irvine and author of “Nutcracker Nation: How an Old World Ballet Became a Christmas Tradition in the New World,” and “Ballet Matters: A Cultural Memoir of Dance Dreams and Empowering Realities.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.