Op-Ed: Posting a hotline number isn’t enough. Break down doors to prevent a suicide

- Share via

It’s a cultural cliché that we Americans are embarrassingly open about our feelings. But we’re not. We’re just good at faking it, smiling broadly and blithely asserting, “Everything’s good.”

Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported the shocking statistic that the suicide rate in the U.S. is up by 25% compared with 1999, an announcement that was bookended by the deaths of Kate Spade and Anthony Bourdain. Ever since, we’ve been flooding social media with posts about suicide hotlines and poignant RIP remembrances of the designer and the chef. Such responses are equivalent to the “thoughts and prayers” that so often accompany school shootings. And they are just as ineffective at preventing another tragedy.

How could they do it? Why didn’t they get help? How could two people that successful end their lives? If these conversations sound familiar, it’s because they are: We said the same things last year about Soundgarden’s Chris Cornell and Linkin Park’s Chester Bennington.

Here’s what many people — many lucky people — don’t understand about depression. It doesn’t matter how much money you have in the bank; it doesn’t matter how beautiful you are, or how popular, or how successful. Depression doesn’t care. It is like demonic possession. Actually, it is possession. You lose your agency. You lose perspective. You are in a dark tunnel, and it just keeps getting narrower and darker until you can see only one option, one way to end unbearable pain. It doesn’t seem selfish; it doesn’t seem sad. It looks like the light at the end of the tunnel, and it feels like relief.

It doesn’t matter how much money you have in the bank; it doesn’t matter how beautiful you are, or how popular, or how successful. Depression doesn’t care.

I should know. I have suffered from depression since I was a kid. At 10, I wrote in my diary, “Don’t be so depressed now. You’ll have plenty of time when you are grown-up.” My 10-year-old self was prescient: I have been on and off antidepressants since my 20s, and I have had at least two bouts of major depression. Two years ago, it happened again. It was my birthday, and a friend took me to a beautiful ocean-side restaurant in Malibu. I spent the whole of the extravagant meal gazing out the window, saying almost nothing. I wasn’t admiring the view: I was thinking about hurling myself into the sea.

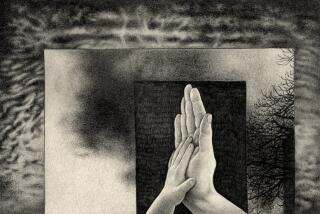

I couldn’t tell my friend how sick I was because I felt guilty and ashamed. She spent a small ransom on a lobster lunch; how could I say I hadn’t even tasted the food? That afternoon, I saw another friend, A., and told her that I was feeling low. A suicide survivor, A. sensed that it was more than the blues. The following day, I wasn’t answering the phone or responding to texts. A. drove to my house, used a crowbar to pry open the front door of my building, and then busted through a window screen to get into my courtyard apartment.

I was at Step 1 in a three-step process: First, the all-consuming need to make the pain stop. Then, “Create a plan.” I don’t think I need to explain what happens next. When A. broke into my apartment, I reacted angrily. I pretended I was OK, that she was overreacting, that everything was fine.

The reality is that A. saved my life. She didn’t call 911 or pull me out of a bloody tub, but her actions woke me up. I had frightened her, which, in turn, frightened me. I called a psychiatrist the next day and went back on meds. Within a few weeks, I started to climb out of the chasm, chastened, a little humiliated — and very grateful.

Suicide is shocking to most of us, especially celebrity suicide. We trot out platitudes about having so much to live for, about the terrible waste. But I never feel shocked because I know that it is possible to play-act your way through life.

When we ask others how they are doing, we don’t really want to know. We prize individuality and privacy; more than that, we prize success. Despair and mental illness don’t square with success. The desperately unhappy feign wellness. They don’t want to admit to friends and family members that they have succumbed to the ultimate American sin of not being able to say, “I’m good.”

No doubt everyone who has posted an admonition to “Get help!,” every reporter who added the National Suicide Prevention 800 number at the end of a news story is well-intentioned. But as a person who has called that hotline, I can tell you: It isn’t enough.

Hotlines are a start — but you can and should do a lot more. If you fear that someone in your life is depressed, make that call yourself. Then make more calls. Get resources lined up — real resources, like therapists and psychiatrists willing to work on a sliding scale. More importantly, be willing to intrude. Commit another American sin: Ask someone how they really are. Keep phoning. Invade personal space. If you are genuinely afraid of what someone might do, take that someone to the emergency room or call 911. A depressed person may well resist your efforts — ignore her protests. Sick people need help, and they are often unwilling to admit it. But they won’t get better on their own.

It’s very possible that the only reason I am here today is because of my friend and her crowbar. Don’t be afraid to use a crowbar. More crucially, don’t be afraid.

Poet Amy Newlove Schroeder teaches writing and ethics at the Viterbi School of Engineering at USC.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinionand Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.