Opinion: Ferguson and our black-white divide

- Share via

There are times – and this is one of them – when I fear this country is incapable of thinking and talking its way through a transition from a racially fractured past and present to a more accepting, tolerant and united future. And that’s because a large portion of the dominant culture – my fellow white Americans – cannot see the world through a perspective other than their own.

As a white male, I won’t pretend that I know at a core level what it is like for African Americans to navigate modern America. But the reactions to the killing of Michael Brown by Ferguson, Mo., police Officer Darren Wilson, and the subsequent lack of action by a grand jury, spotlight yet again that while white and black Americans occupy the same country, many seem not to be looking at the same world.

Let me share a couple of comments that illustrate this divide. A few days ago I posted an item about author Daniel “Lemony Snicket” Handler’s objectionable joke about author Jacqueline Woodson, who is black, being allergic to watermelon (Handler, who is white, later apologized for what he admitted was a racist joke). Someone sent me this email in response to the blog post:

“It is writers like you who do more to hurt blacks by making excuses for their crimes and acting like they cannot lead better lives because of racism. Racism is not an excuse for bad behavior. Black on black crime is off the charts. Is that white people’s fault too? You should read Thomas Sowell who says Liberals want blacks to be dependent on government to get their votes. They call blacks like him who want fathers to take responsibility for their children and to work hard and stop committing crimes Uncle Toms. Yes there are some racists against blacks but there is also racism against whites by blacks yet that is rarely mentioned by writers like you.”

Note that the blog post had nothing to do with crime, government support programs, personal responsibility or bad behavior by a black person. In fact, it was about precisely the opposite - bad behavior by a white person. Yet in the eyes of the reader, black America was at fault (as are journalists who write about race).

The second revealing comment (posted online) came in response to a Times editorial that the grand jury decision not to indict Wilson is not a vindication of the Ferguson Police Department.

“Watching Brown’s family’s lawyer trying to gin up a civil rights case, and some of the incredible things said by Blacks who are in positions of authority, I can only infer that Black people as a whole will never decide to become a productive, useful, law abiding part of society, and will cling to nothing more than their hatred of anything remotely associated with White people.”

Compare those outlooks with these. The first is from Gary Fields, a Wall Street Journal reporter, recalling his detention at gunpoint years ago by a local sheriff’s deputy who was part of a swarm of Louisiana police trying to find a murder suspect described as black, 5-6, around 40 years old and riding a bicycle. Fields, who was walking home in broad daylight from a bowling alley, had already been warned by a state trooper about the gunman on the loose. Fields wrote that the sheriff’s deputy emerged from the car with his gun drawn, pushed Fields onto the hood and handcuffed him:

“I was saved when the state trooper who had first stopped me drove back by. He ripped into the deputy, asking him questions, and I answered — which, in another situation, could have been a comedy routine. Does this kid look 5-6? I answered, I’m 6-3. Does this kid look 40? I’m 17. Does this kid look 150 pounds? I’m 230.

“The trooper ran through several descriptors for the suspect. I matched just one of them. I asked, ‘Outside of the basic black, is there any part of the description I fit?’

“’Don’t get smart, boy,’ the deputy hollered. But the trooper, who also was white, ended the discussion. He was livid. I thank God for him.

“Years later, there is still no doubt in my mind that if I had moved in any way that frightened or angered the deputy, he would have shot me, and a reason would have been found to justify it.”

Now this from Stephen Henderson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and editorial page editor for the Detroit Free Press:

“As black people, America breaks our hearts over and over again. No group has more reason to resent this country’s very existence, built as it was on the notion of unmovable racial inferiority. And yet, no Americans have persevered so much, for so long — journeying from three-fifths of a man to president of the U.S. in just more than 200 years.

“But now, in Ferguson and other places, we are being told that our children are menacing in their very essence, and that they can be killed for the most mundane transgressions. Walking through a subdivision where they don’t live, like Trayvon Martin. Or engaged in petty crime, like the unarmed robbery Michael Brown was captured on video committing.

“The fear sweeping black families across the country is not about their children’s innocence or guilt, but about the brutality with which authority is exercised, and the insistence that it’s always justified.”

Is there any common ground to be had between the experiences and expectations of Fields and Henderson, and our comment and email writers? I’m skeptical - particularly because so many white Americans maintain a willful ignorance of, or rationalization for, the scope of killings of African Americans by police. Significantly, that is a statistic the federal government doesn’t bother collect, a message that says, your lives matter so little we won’t even count them when they end. (The Daily Beast reports that “young African Americans are killed by cops 4.5 times more often than people of other races and ages.”)

Years ago, as a journalist in Detroit, I noticed that whites and blacks had different views of the city’s history (something I later explored in a book). When talking with white suburbanites about Detroit, the conversation often involved some variation of when their parents or grandparents left the city, and what “they” (African American Detroiters) had done to the old neighborhood. Rarely did I hear a white suburbanite talk about the family move in terms of personal and economic abandonment of the old neighborhood, which was, in fact, what the suburban exodus amounted to.

For black Detroiters, the personal history often involved an ancestor moving north from the agricultural South, the growing up amid the exodus of white neighbors and good jobs, and anecdotes about how racism played out in their lives in a place where police actions over decades fed an instinctive distrust.

If our conceptions of history of the same place veer this widely, is there any hope for finding common ground? Maybe. But if we’re going to get anywhere, we need to move beyond the narrow prisms of personal experience and presumption, and view these issues from broader perspectives.

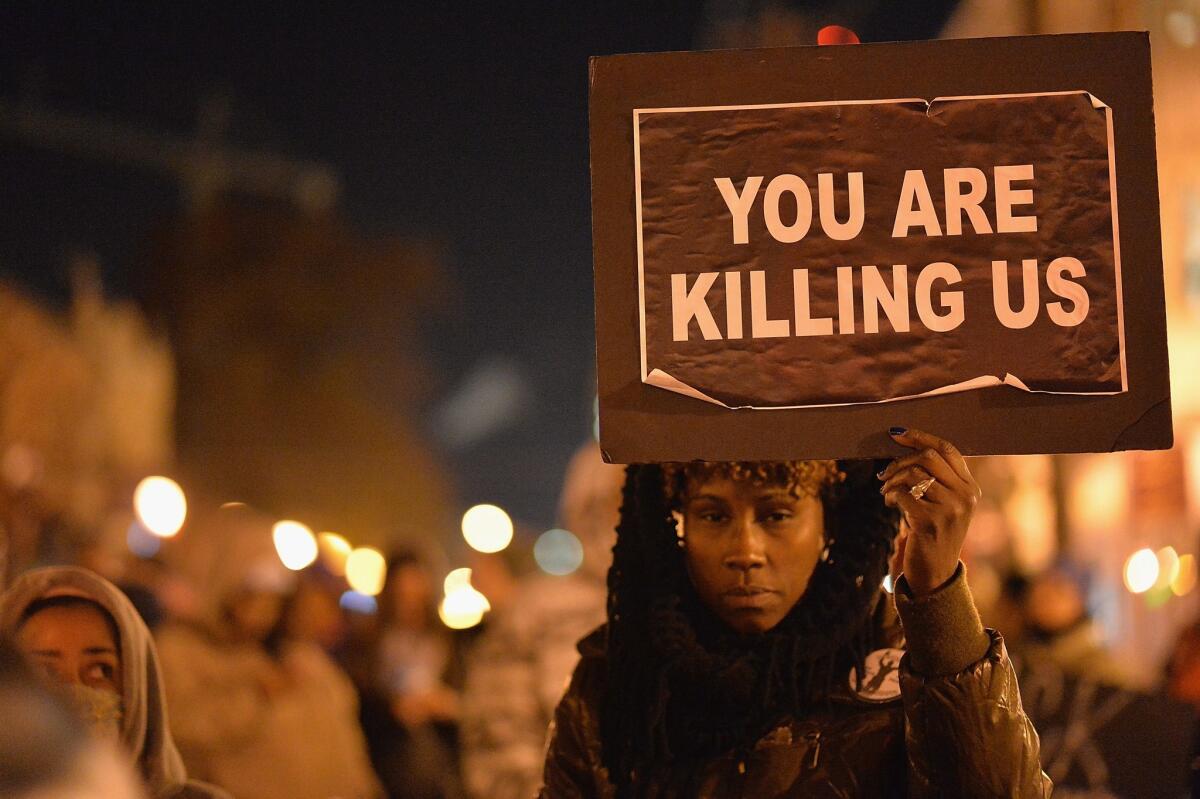

You can’t solve a problem if you don’t even try to understand its cause. The protests across the country this week have less to do with the single killing of an unarmed teen than with abject frustration at a society that seems to be eternally out of balance.

As Martin Luther King Jr. said in 1966, while describing riots as “self-defeating and socially destructive,” a “riot is the language of the unheard and what is it that America has failed to hear? It has failed to hear the economic plight of the Negro poor which has worsened over the last few years.”

Add to that a current and stubborn lack of equality and justice, and you wind up with people taking to the streets from Ferguson to Los Angeles to Boston.

We, as a nation, need to listen closer, and to hear better.

Follow Scott Martelle on Twitter @smartelle.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.