Opinion: Justice Scalia’s method triumphs in Obamacare case, if not his views

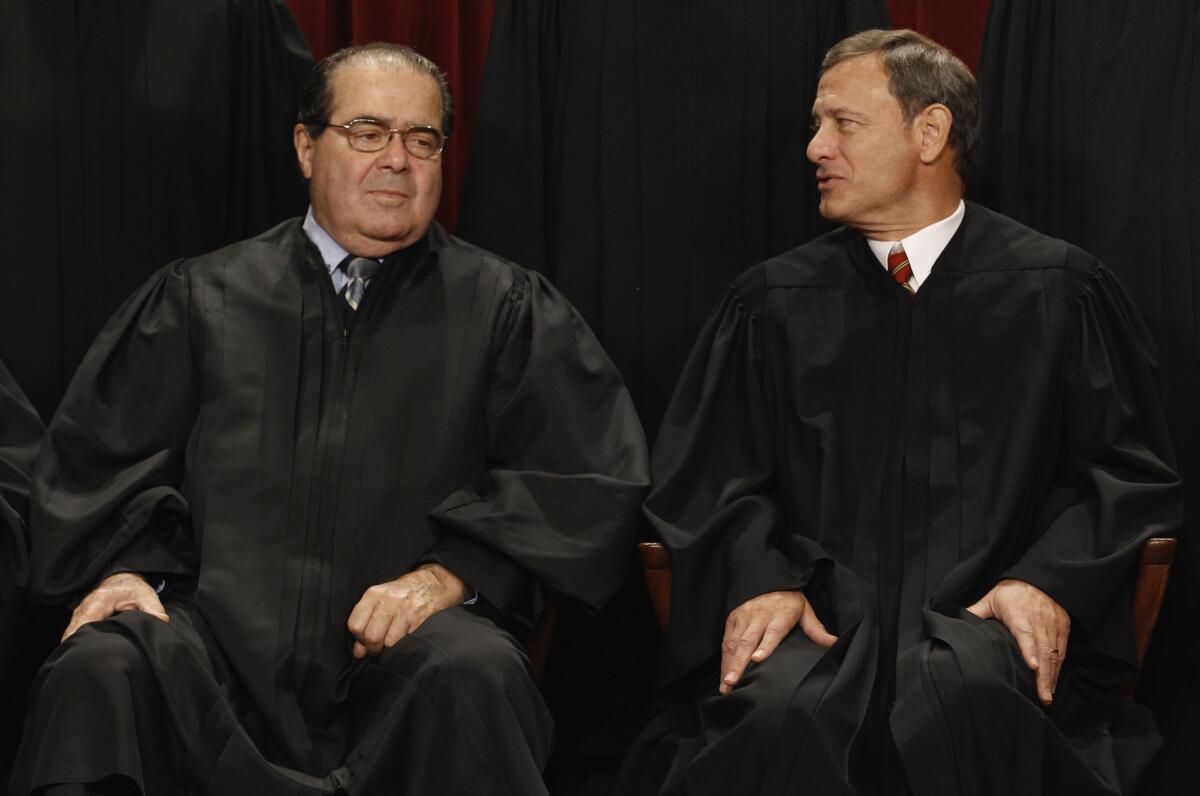

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, left, and Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. wait for an official court portrait to be taken in 2010.

- Share via

It’s not been a good week for Justice Antonin Scalia, who was on the losing end of major decisions on same-sex marriage, the Affordable Care Act and housing discrimination. But on the Obamacare case, at least, his views on how the court should interpret laws prevailed spectacularly.

And not necessarily in a helpful way.

Scalia is a leading proponent of textualism, the approach to statutory interpretation that calls on judges to ignore the legislative history and focus with laser-like precision on the text itself. That was once a, shall we say, non-mainstream approach to deciding what lawmakers meant when they enacted a disputed statute. But textualist discipline guided not only Scalia’s dissent in the Obamacare case, King vs. Burwell, but also the majority opinion written by Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr.

What’s striking is that the sole issue in the case was what Congress meant by one phrase buried in the 955-page statute. And in answering that question, not once did Roberts look to the bills, reports and debates that were the precursors to the ACA.

Funny, but conservative legal theorists once thought that textualism would actually win the case for King. The plaintiffs in the case -- four lower-income Virginians who chafed at the idea of being forced to buy health insurance at a fraction of the cost most people pay -- said that one provision in the law dealing with the maximum amount of the subsidy effectively set the level at $0 for anyone who did not get their coverage through an exchange “established by the State.”

Scalia agreed, writing in his dissent that the proper reading of the provision was abundantly clear, even when read in the context of the full statute. “Words no longer have meaning if an Exchange that is not established by a State is ‘established by the State,’” he argued, steam no doubt rising from his scalp at he wrote.

Roberts looked outside the text of the ACA to establish a baseline of sorts for Congress’ healthcare reform efforts, citing the problems that resulted from the partial reforms that several states enacted in the 1990s and 2000s. But in trying to determine what Congress meant when it included “established by the State” in the provision in question, he confined his analysis to looking at how the phrase is used elsewhere in the law, and whether King’s interpretation would lead to absurd or impossible effects on other passages.

In other words, he stuck to the text to try to divine the provision’s meaning.

My colleague Mike McGough observes that Scalia and other textualists contend that “it’s better to wrestle with a less than crystal clear law based on its language and common understanding than it is to delve into legislative history, which is often contradictory -- as when two senators give floor speeches drawing different conclusions from the same bill.” And in the case of the ACA, the legislative history is incomplete -- the final version was thrown together by Senate Democratic leaders by privately combining the work of two committees, so judges don’t have the usual committee or conference report elaborating on the thinking behind the various provisions.

But the legislative history that does exist -- the House Energy and Commerce bill that came first, then the proposals by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and Senate Finance committees that were blended into what became the ACA -- sheds quite a bit of light on lawmakers’ thinking about subsidies. I went over that in detail in a blog post last year, which looked at how each committee responded to its predecessors’ approach to the exchanges.

The bottom line: None of the panels sought to use subsidies as a cudgel to force states to create an exchange. Even the Senate health committee, which wanted to pressure states into enacting changes in their insurance laws, wouldn’t have withheld subsidies from those that did not comply.

Although that’s not a definitive reading on congressional intent, it does help contradict the narrative advanced by the plaintiffs. And the bills also help explain what lawmakers were trying to accomplish with the phrase “established by the State” -- to distinguish a state-centric system of exchanges, which the Senate favored, from a federally driven one, which was the House’s approach.

Regardless, the court agreed with the administration that Congress intended to make subsidies available throughout the country, not just in the states that set up their own exchanges. And Roberts did so Scalia’s way, even though he followed the path to a completely different conclusion.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.