Column: With Harvey Weinstein, this women’s advocate fell off a moral cliff

- Share via

Honestly, I was not expecting to learn that two attorneys — one a well-known champion of women, the other a pillar of the establishment — would turn out to be the bad guys in the new book “She Said,” by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, the New York Times investigative reporters who broke the Harvey Weinstein sex harassment and assault scandal in October 2017.

We already knew so much about the disgusting behavior that Weinstein inflicted on his employees, and on actresses who wanted to work for him, that the depraved details came as no surprise: the hotel room meetings, the bathrobes, the pleas for naked massages, the cajoling, the brute force, the threats of retaliation, the actual retaliation, the alleged rapes.

All of that is familiar territory now, nearly two years after the #MeToo movement was ignited by spectacular investigative journalism at a number of outlets, including the Los Angeles Times.

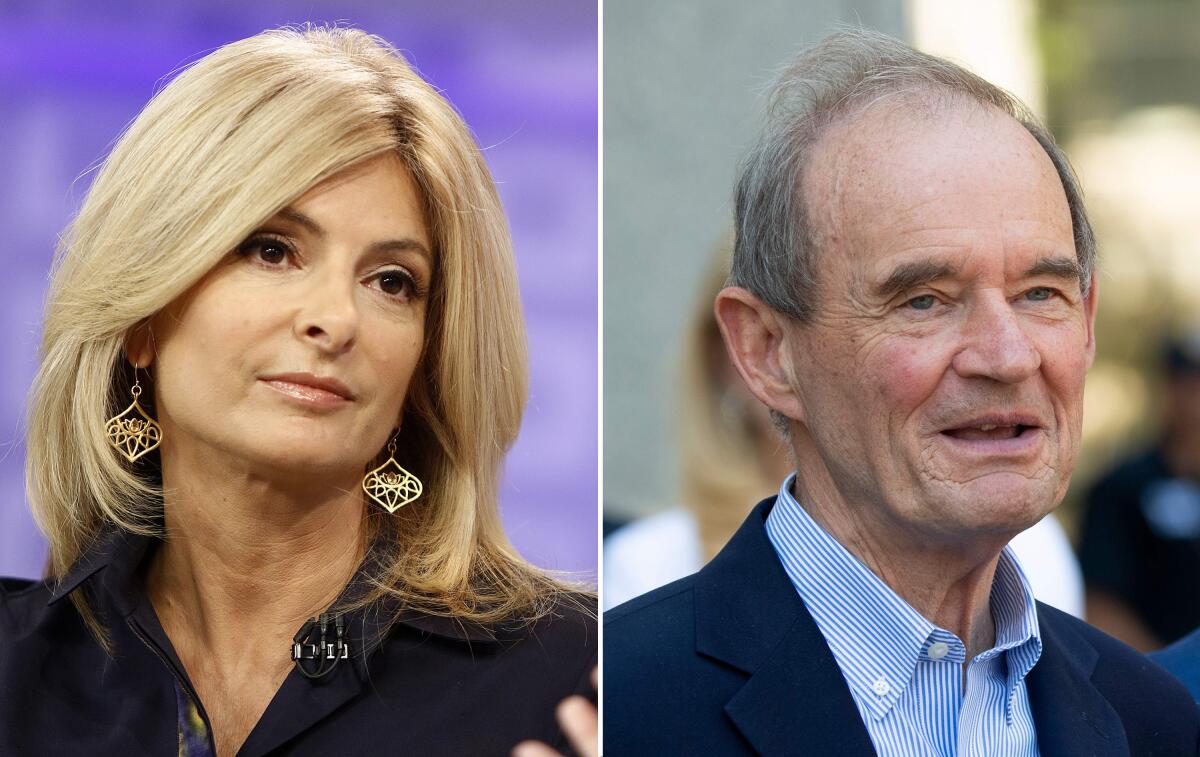

What did come as a shock is the way that attorneys Lisa Bloom, a champion of women’s rights, and David Boies, who famously argued in favor of gay marriage, among other things, took up Weinstein’s cause in brutal, compromising ways.

Was it only coincidence that Bloom’s book on the Trayvon Martin case was going to be made into a miniseries by the Weinstein Co.? Or that Boies, according to Kantor and Twohey, was angling for a role in a Weinstein film for his actor daughter, Mary Regency?

I won’t focus much on Boies, who, while representing the New York Times in legal cases, was simultaneously working to undermine the Times’ investigation of Weinstein. (The New York Times fired him.)

But how can Bloom, who, like her mother, Gloria Allred, has carved a place in the legal world exacting justice for women who have been abused, harassed and discriminated against, have thrown herself off such a precipitous moral cliff?

A contrite Bloom, who declined my interview request, has tweeted her regret and described her involvement with Weinstein as “a colossal mistake.”

Oh, Ms. Bloom, it wasn’t just a mistake.

It was a total, humiliating sellout.

::

Kantor and Twohey obtained a December 2016 pitch written by Bloom to Weinstein, outlining how the two of them, together, could undermine Weinstein’s first public accuser, the actor Rose McGowan, who alleged that Weinstein had raped her in 1997 and had received a $100,000 settlement from him that included a nondisclosure agreement, or NDA.

McGowan was writing a memoir; Weinstein wanted to impede her. Or, failing that, destroy her.

“I feel equipped to help you against the Roses of the world because I have represented so many of them,” wrote Bloom, who called McGowan “a disturbed pathological liar.”

She recommended sending McGowan a cease-and-desist letter, and placing “an article re her becoming increasingly unglued, so that when someone Googles her this is what pops up and she is discredited.”

In the memo obtained by Kantor and Twohey, Bloom, whose law firm is in Los Angeles, offered a six-point plan to paint Weinstein as a feminist committed to making the film world a better place for women to work. She suggested that she and Weinstein appear on TV together “in a pre-emptive interview where you talk about evolving on women’s issues, prompted by the death of your mother, Trump pussy grabbing tape and maybe nasty unfounded hurtful rumors about you…. You should be the hero of the story, not the villain. This is very doable.”

She advised Weinstein to set up a charitable foundation “focusing on gender equality in film, etc. Or establish the Weinstein Standards, which seek to have one-third of films directed by women or written by women, or passing the Bechdel test (two named female characters talk to each other about something besides a man), whatever.”

Whatever?

::

Kantor and Twohey did not just set out to find out what happened, but how.

How was it possible that Weinstein, whose predations were an open secret in Hollywood, was able to get away with his contemptible behavior for so long?

They have created a damning portrait of a system that is designed to protect perpetrators by silencing victims while purporting to make them whole.

The system is built on sleazy tactics like those that Bloom suggested to Weinstein, of course.

But also with cash settlements that include the prolific use of extremely strict nondisclosure agreements. These agreements ostensibly provide confidentiality to women who may not want to go public with their accusations, but they also allow predators to keep preying without professional fallout, as long as their pockets are deep enough.

The headline on Kantor and Twohey’s first, explosive New York Times story on Weinstein was not just about his harassment, but about that system that allowed him to do the same thing over and over again with no legal or professional consequence: “Harvey Weinstein Paid Off Sexual Harassment Accusers for Decades.”

Victims’ attorneys may argue that NDAs offer essential protection to women, and usually net them higher settlements (of which the lawyers usually take 40%). But in practice, NDAs are invaluable tools for harassers.

“I really hate NDAs,” said Oakland-based employment discrimination attorney Leslie Levy. “The ability to talk about what happened is critical to the healing process. The act of harassment or rape and assault is all about power. You leave the power in the perpetrator’s hands when you allow him to gag the woman.”

As Levy points out, a man who pays a million dollars to a woman he has assaulted is probably not going to go around blabbing about it.

And victims risk losing it all if they breathe a word to anyone.

One of Weinstein’s victims, Rowena Chiu, told Kantor she felt she’d signed “a deal with the devil.”

In California in 2017, state Sen. Connie Leyva had considered introducing a law that would strictly limit confidentiality clauses in sexual harassment and assault settlements. In “She Said,” Kantor and Twohey report that Allred threatened to lobby hard against the bill.

“With Allred’s threat,” they wrote, “an effort to reform the system and protect victims’ voices died before it was ever introduced.”

A year later, however, then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a bill that would ban NDAs in sexual harassment, assault and sex discrimination settlements.

Both Allred and Bloom gave the law their tepid approval. Allred said it could make getting maximum settlements for victims more difficult. Bloom acknowledged that the law “is definitely a step in the right direction.”

So maybe it will have the effect of lowering the amounts of money harassers are willing to pay to make claims go away. Maybe it will force women into litigation, which can be expensive and painful.

But it will remove their gags, let them talk about their traumas.

And maybe — just maybe — it will discourage powerful men from taking advantage of their far less powerful underlings.

And hasn’t that been the point of the #MeToo movement all along?

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.