Editorial: Aftershocks from Trump’s impeachment further fracture civility and cooperation in Washington

- Share via

Pictures being worth at least a thousand words, two images from Tuesday’s State of the Union address quickly came to signify the partisan rancor in Washington. One was of President Trump seemingly declining to shake the hand of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi; the other was of Pelosi tearing up the text of the president’s speech after he delivered it, a gesture of contempt that sent Republicans into a froth of mostly feigned outrage.

Those images eloquently convey the poisonous partisanship that makes it unlikely that comity and cooperation will return to the capital now that Trump has been acquitted by the Senate. This state of affairs is, of course, deeply regrettable. But it’s a mistake to attribute this angry estrangement solely to an impeachment process that began in the House and was resolved in the Senate, largely along party lines, the day after Trump spoke to Congress.

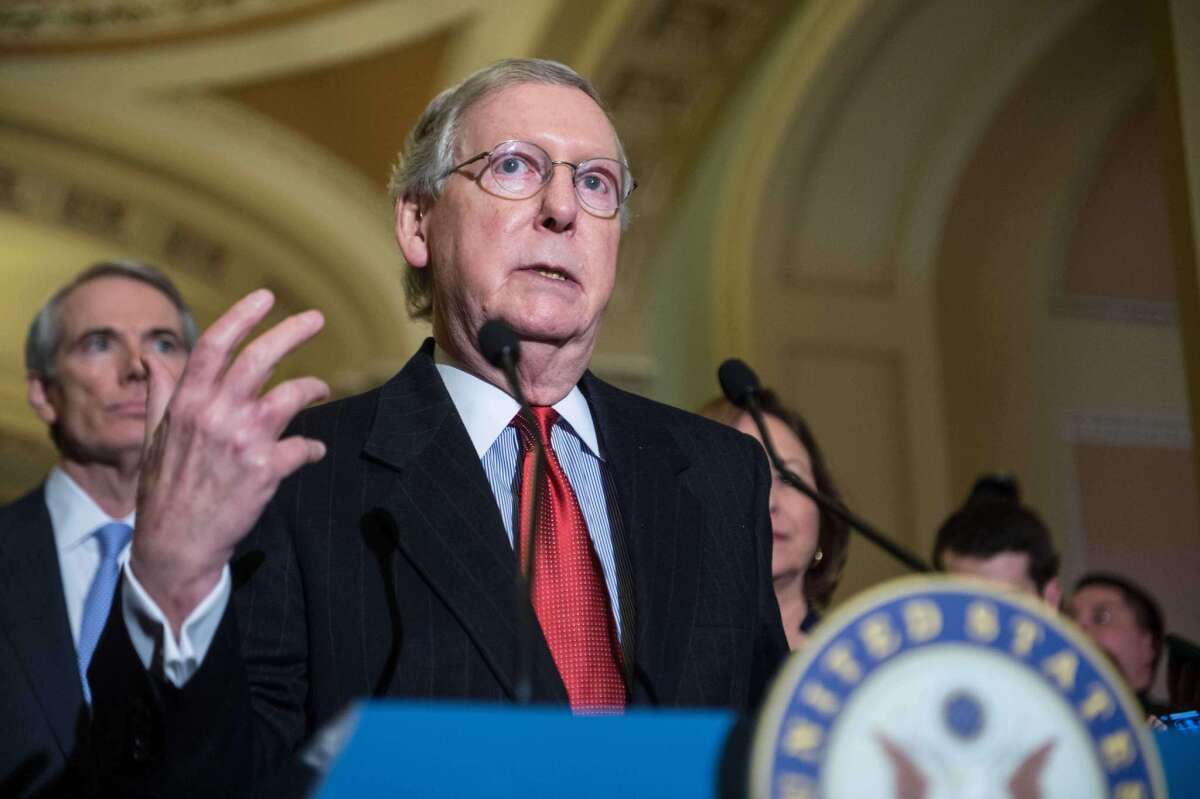

The bad blood has been boiling since long before the rise of Trump, and it has many causes. One is the drawing of politically lopsided congressional districts in which candidates have no need to reach out to voters of the other party, but have to fend off challenges instead from more extreme members of their own side. Another is the willingness of both parties in the Senate — but especially Republicans — to trample on norms in pursuit of immediate advantage. The most egregious example of that was when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) prevented his chamber from considering a Supreme Court nomination for almost a year in order to deny President Obama the opportunity to fill the seat.

Partisanship at all costs also has warped the relationship between the branches of the federal government. Republicans who complained about the Obama administration’s refusal to provide documents to Congress were only happy to have Trump insult the legislative branch by stonewalling congressional requests for documents and testimony that would shed light on whether he committed impeachable acts in pressing Ukraine to investigate former Vice President Joe Biden. Similar hypocrisy is evident in the way many Republicans have supported Trump’s decision to make policy through ill-considered executive action — a practice for which Republicans assailed Obama.

No doubt Pelosi’s reluctant decision to announce an impeachment inquiry into Trump’s egregious misconduct on Ukraine exacerbated already deep partisan divisions. That doesn’t mean that she was wrong to do so. Republicans like to say that the impeachment was just an attempt to nullify the last election or steal the next one, and that as a result of it, impeachments will now happen whenever the House and the presidency are controlled by opposing parties. Those arguments ignore the gravity of Trump’s abuse of power.

Impeachment indeed ought to be a rare remedy for presidential misconduct, but Trump brought it on himself by hijacking foreign policy for his personal benefit, a violation Congress couldn’t ignore. To assert that House Democrats somehow made impeachment a routine procedure, you have to believe that future presidents will be as blind to or contemptuous of the norms of governing as Trump has been. We’re not that cynical.

Nor was the legitimacy of this impeachment undermined by the refusal of Republicans in Congress — with the admirable exception of Sen. Mitt Romney — to hold Trump accountable. That the votes to impeach and acquit Trump were largely along party lines isn’t the Democrats’ fault or an indictment of the way the House chose to conduct its investigation, despite all the Republican complaints about a supposed lack of due process for the president. The partisan nature of the votes reflected the unwillingness of Republicans, including some who must have been privately appalled by Trump’s actions, to offend the vindictive president and his excitable base.

It would be unrealistic to expect that Republicans and Democrats would be singing “Kumbaya” together even if Trump weren’t in the White House. The extreme partisanship that has undermined Congress’ work for the American people has deep roots. But even modest progress toward bipartisan comity and cooperation in Congress is impossible so long as Trump remains in office. This, after all, is the president who after his acquittal denounced his political opponents in vulgar terms (“Adam Schiff is a vicious, horrible person; Nancy Pelosi is a horrible person”). And he has congressional Republicans in his thrall.

There are a multitude of reasons for voters to remove Trump in November, but among them is the salutary effect it would have on the orderly functioning — and self-respect — of Congress.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.