Op-Ed: In this Super Bowl matchup, echoes of football’s march toward racial equality

- Share via

Heading into this Sunday’s Super Bowl, the Los Angeles Rams and the Cincinnati Bengals have faced off only 14 times in the half-century since the modern National Football League was formed by a merger. To be even more precise about it, five of those games should carry an asterisk, because they took place when the Rams’ owners had moved the team to St. Louis.

Although the Super Bowl LVI matchup is more of an intriguing rarity than a storied rivalry, a thread of history does connect the Rams and Bengals, a thread that runs back in time through two former stars to another kind of Super Bowl, the one that for decades crowned the champion of Black college football.

It was Kenny Washington and the Rams that broke the league’s color barrier, a year before Jackie Robinson and the Dodgers integrated Major League Baseball.

That connection serves as a reminder of the NFL’s long-complicated history around race, especially as the league and three of its teams have been sued by former head coach Brian Flores of the Miami Dolphins, who alleges racial bias in hiring in the head-coaching ranks.

The thread begins with two former players. James “Shack” Harris led the Rams to the National Football Conference title game twice in the mid-1970s, a groundbreaker as a Black quarterback. Ken Riley started at cornerback for the Bengals in the 1982 Super Bowl, culminating an illustrious career that still ranks him fifth in league history in interceptions.

They have to not only raise their voices but take action, whether that’s a summit like the one held in support of Muhammad Ali in 1967 or a flat-out work stoppage.

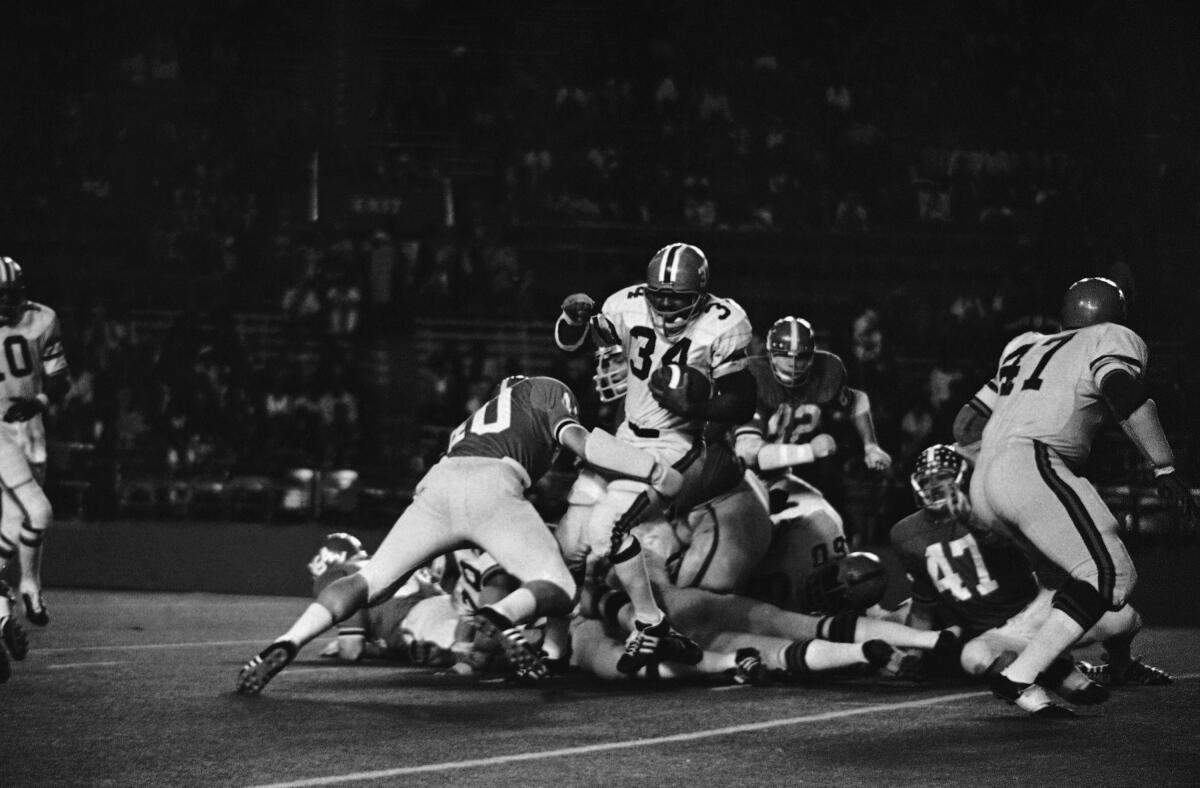

And Harris and Riley had each quarterbacked their teams from historically Black colleges — Grambling and Florida A&M, respectively — in the de facto Super Bowl that was called the Orange Blossom Classic and took place in Miami annually from 1947 through 1992. One could even argue that their 1967 game was the greatest Black college title game ever, a showdown between two future pro stars and two perpetually dominant teams helmed by two coaching legends, Eddie Robinson of Grambling and Jake Gaither of Florida A&M. Before a sold-out crowd in the Orange Bowl stadium, Grambling needed a last-play sack of Riley to hold on for a 28-25 victory.

“The Orange Blossom Classic, the OBC, was in every way the Super Bowl for Black college football,” said Michael Hurd, a historian who has written several books on Black college and high school football. “It had all the trappings of the NFL event, but with a decided Afrocentric bent. For the OBC, Black fans and media hordes descended on Miami for a week of parties, parades and other festive events in a holiday atmosphere for the game of the year. Miami’s Black neighborhoods, Overtown and Liberty City, were teeming with tourists and fans for a culture feast at restaurants, clubs and other venues.

Look at the abysmal racial records of big corporations and the U.S. Senate.

“Like the Super Bowl,” he continued, “Black college teams targeted the game for its national exposure and the opportunity to claim supremacy. The game was heavily hyped, and for the OBC that meant saturated coverage from Black newspapers like the Pittsburgh Courier, Atlanta Daily World, the Chicago Defender, and only a game of this magnitude could bring out normally disinterested media outlets like Florida’s white media.”

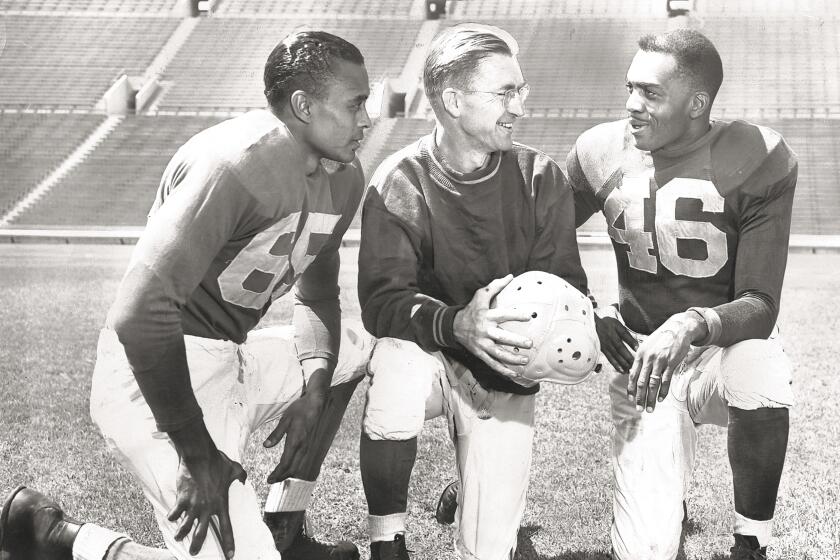

All these years later, James Harris vividly recalls the importance of the Orange Blossom Classic in Coach Robinson’s master plan to have his quarterback break the position’s color line in the NFL. Robinson had overhauled Grambling’s entire offensive scheme in order to feature Harris as a classic, pro-style, dropback quarterback, knowing that when Black college quarterbacks showed their speed and mobility, those traits became the excuse for pro teams to switch them into wide receivers or defensive backs.

Gruden is the epitome of how the game is played in a multibillion-dollar industry in which the leaders don’t expect anyone to hold them accountable.

At the Orange Blossom Classic, Harris would be on display for the first wave of Black scouts in the NFL and its then-rival American Football League — Bill Nunn of the Pittsburgh Steelers, Lloyd Wells of the Kansas City Chiefs, Tank Younger of the Rams. The 1967 classic was also televised on tape delay in Atlanta, Philadelphia, Washington and New York, giving Black college football its greatest national exposure to date.

“If you put each one on its level, the Super Bowl and the Orange Blossom Classic, it was as big a game,” said Harris, who retired from pro football in 2015 after a lengthy career on the field and in the front office, where he won a Super Bowl ring with the 2000 Baltimore Ravens. “With the media attention, with all the scouts being there, it had that championship atmosphere.”

Such prominence was both the goal and the dream of J.R.E. Lee Jr., who conceived of the Orange Blossom Classic in the early 1930s. At the time, his father was president of Florida A&M. After about a dozen years of bouncing among other Florida cities, the game settled into Miami in 1947 and began establishing a tradition in both sports and civil rights. Florida A&M, invariably one of the top Black teams, would host the highest-rated opponent each December, creating the functional equivalent of a Black championship game.

The initial OBC game in Miami, between Florida A&M and Hampton Institute, marked the first time Black spectators were permitted in the main stands of the Orange Bowl. The weeklong festivities leading to each year’s game brought entertainers such as Nipsey Russell and Sammy Davis Jr., the first cohort of Black corporate executives, and the largest turnout of Black spectators for any annual event since the Negro League’s baseball all-star game.

Not very effectively, though. Cherry-picking quotes didn’t help him defend his COVID deception.

On the gridiron, the OBC supplied recognition to Black college teams amid the paradoxes of the Jim Crow era. On the one hand, segregation ensured that the star players and brilliant coaches who were barred from every white school in the South invested their talents into the Black football universe of Grambling, Florida A&M, Southern University and Tennessee State, among other colleges. On the other hand, considering the scant regard such teams got from the mainstream media, Black college football was being played “behind God’s back,” as Tennessee State coach John Merritt once put it.

The 1967 game contributed to the struggle for visibility, and attested, too, to how long and arduous that struggle would be. Voted the game’s most valuable player, Harris went into the NFL draft after one more season at Grambling, but because of his insistence on playing quarterback, he was not chosen until the eighth round. Even so, he started as a rookie for the Buffalo Bills and then had his finest years with the Rams. They ended cruelly in 1976, however, when the team’s owners overruled head coach Chuck Knox, traded Harris away, and drafted or traded for four white quarterbacks to replace him.

As for Ken Riley, whose skill set and physique resembled those of such current NFL quarterbacks as Kyler Murray of the Arizona Cardinals and Russell Wilson of the Seattle Seahawks, he never even had the chance to compete for the quarterbacking job on the Bengals before being shunted to cornerback in training camp. He died in 2020, having been repeatedly and inexplicably passed over for the NFL Hall of Fame.

The Orange Blossom Classic was revived last September, though no longer as a championship game. An influx of former NFL players and coaches have become head coaches at historically Black colleges — Deion Sanders at Jackson State, Eddie George at Tennessee State, Hue Jackson at Grambling — and inspired visions of another golden era. And on the field of SoFi Stadium two weeks ago, the Rams received their trophy as NFC champions from none other than James Harris.

Watching that ritual, one had to wonder whether it carried a whiff of atonement for past injustice, or an unwitting acknowledgement of the NFL’s still-unfinished racial business.

Samuel G. Freedman, a professor of journalism at Columbia University, is the author of nine books, including “Breaking the Line,” about Black college football and the civil rights movement.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.