Op-Ed: L.A. transformed my relationship with football — and with myself

- Share via

Los Angeles saved my life. I arrived in the city as a broken NFL player, after suffering a terrible injury, and at the heels of great personal grief.

There was the sun and the allure. But I was also eager to be something more than football. Whether it be for stardom or freedom, newcomers came to L.A. every day, fleeing their social constraints and transcending to the truest forms of themselves. I had to find a place that was mine, somewhere unfamiliar and far from my Texas roots, to get to know the parts of myself I’d hidden for too long. As all eyes turn to L.A. ahead of the Super Bowl, I’m reminded of how this place has transformed my relationship with football — and with myself.

I landed in L.A. after one of the worst years of my life. I moved without a big NFL contract and had no family or friends around. As a starting defensive end for the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, I endured a horrific shoulder injury during the 2017-2018 season. As many young athletes do, I played through the pain. But my contract wasn’t renewed. Despite shoulder rehab, I had a disappointing preseason in Buffalo, N.Y.

Seventy percent of the NFL’s players are Black, yet the league has only 2 Black head coaches. A lawsuits asks why.

Meanwhile, I lost my closest friend and college teammate, Joe Gilliam, to cancer in 2018. Joe’s love and brotherhood created the only safe space where I felt like I belonged. He was the first person whom I told about my sexuality. As a closeted bisexual Black man in professional sports, I had few places to fully be myself. Without him, I came apart.

Loneliness was crippling at first, and I was reluctant to leave the house, yet L.A.’s creative energy lured me. I had lost so much, but L.A. offered so much more to gain if I could gather the courage to discover this place I’d known in movies and books and dreamed about. I started to explore the city and found parts of myself I hadn’t known. It came slowly at first, like dipping your toe into the pool to check the temperature, then jumping in.

I devoured poetry readings across L.A. I’d loved poetry from a young age, but besides Joe, few people knew. I thought it conflicted with perceptions of a tough football player, making me seem weak or soft. My favorite was Da Poetry Lounge held at a high school on Fairfax Avenue. After several weeks of listening, inspired not only by the poets’ talent but by their diversity — every skin color, sexuality, body type, style — I finally decided to share. The first poem I read was about Joe. Being under those lights was the first time outside of football that I had felt so alive and worthy.

Even Joe felt closer. On long hikes in the canyons and mountains, I felt his presence. Whether it was hiking to Griffith Observatory, a place I’d idolized since watching “Rebel Without a Cause” as a child, or along a more secluded trail in Malibu where the boundless mountains and ocean revived my spirit.

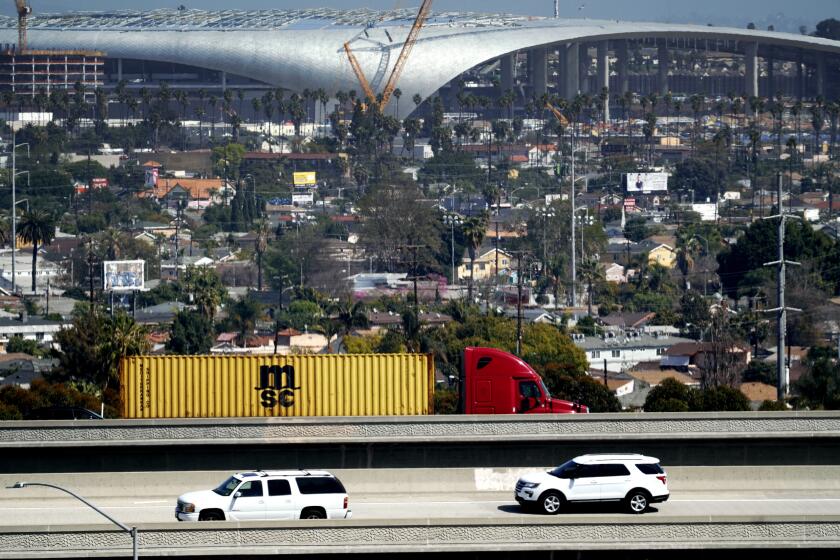

I also reconnected to football here. At Chargers and Rams games, as SoFi Stadium roared to life, I realized that my love for the sport was unconditional, whether playing or watching from the bleachers. How could I not love football? It gave me a full scholarship to Purdue, taught me integrity and hard work. It gave me Joe and so many others whom I still considered brothers. Football could be a major part of my identity, something to be proud of, as long as I embraced the other parts as well.

SoFi Stadium boosters want to stoke the narrative that Inglewood’s giant shiny new object ensures a bright future for the city. But at what costs?

L.A. became a mirror. The city was multifaceted and so was I. I finally loved what I saw staring back at me. This led me to make a big decision, after nine months in L.A.: In August 2019, as an NFL free agent, I came out as bisexual. Though it felt like a beautiful beginning, others thought football would fade away for me. Being among the first to do something is always scary. In an unexpected way, I became more involved with football than ever before, whether I returned to the field or not. I began working with NFL executives to find ways to make the league more inclusive, while mentoring younger players.

Last year, I cheered when Carl Nassib became the first active NFL player to come out as gay. LGBTQ players still face many challenges, such as a lack of representation, toxic masculinity, unwelcoming team environments and erasure. But there’s positive change. People are embracing players for being themselves and standing up for what they believe in beyond football.

I’d love to play football again, and this weekend, the game is coming to my doorstep. The NFL has invited me to attend the Super Bowl on Sunday, with my boyfriend. L.A. is a place where you can embrace every part of yourself, and I think the NFL is getting closer to that as well.

R.K. Russell played for the Dallas Cowboys and the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. He is working on a memoir.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.