Op-Ed: Want to shape your bicultural child’s sense of self before society does? Lead them to books

- Share via

As I travel to speak at schools across the country, I am sometimes the first Latinx author students have ever interacted with, even in communities with high Latinx populations.

If that seems unbelievable in a country where more than 62 million people identify as Hispanic or Latinx, consider that in 2021, only about 9% of children’s books were written by Latinx people. Even fewer (7.6%) were about us.

In addition, we’ve just survived two years of school lockdowns that have profoundly disrupted our children’s lives and learning, with disproportionately negative effects on communities of color, according to the Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights. Disparities and barriers to learning grew worse in many areas, including language-acquisition skills and declining college enrollment.

And now, we are facing an alarming rise of book challenges that take direct aim, in part, at cultural content in kids’ books that often speaks the point of view and experiences of our vast and varied communities. There were almost 1,600 individual book challenges in 2021, the most recorded in a single year by the American Library Assn.’s Office of Intellectual Freedom, which began tracking the data in 2000.

But here’s what I see time and time again. Books and story — even very culturally specific ones — can bring kids to knowing themselves and others better. Encouraging your kids to have a relationship with books could be the most impactful thing a parent of color can do.

So, while it is true that my work centers on Latinx main characters and their families, with careful detail to the specificity of our lives, it is also true that my characters’ experiences speak to the longings of all children: to be loved, to have friends they can trust, and to feel seen and heard as they grow up and make decisions of their own.

The current climate of weaponizing children’s books for political gain threatens that simple act of connection. It also presents a deeper risk to children’s ability to develop accurate images of themselves as people with rich histories, roots and achievements.

Denigrating multilingualism is rooted in the desire to restrict who can belong here. Saying our true names is one way to fight that idea.

Between 2010 and 2019, newborns contributed to the growth of the Hispanic population in the U.S. more than any other group, according to Pew Research.

What that means, especially in California — which has the highest Hispanic population in the nation — is that we’re looking at a population of schoolchildren who identify as bicultural at a time when cultural sensitivity is under attack for being divisive and un-American.

Where does that leave bicultural kids? What does that do to their sense of self?

I grew up as a bicultural child in New York. My parents were refugees from Cuba, a country they would never see again. My mother did what she could to honor my North American identity, since I’d been born here shortly after her arrival. I was given an American name (Margaret Rose), unlimited access to “Romper Room” on TV and, later, a set of World Book encyclopedias she bought in installments.

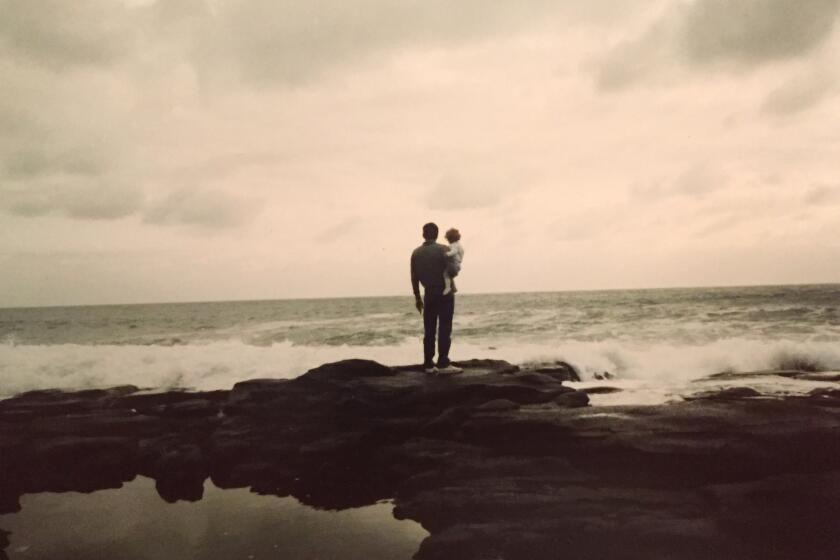

But she had the wisdom to feed my understanding of my Cuban heritage with a passion that is a signature of all who are displaced. She made those connections mostly through oral tradition because that’s what was most available then. Through her many stories about the island — her career as a teacher, the beauty of the Sagua La Grande River, her father’s rural school — she addressed her own trauma while giving me a sense of my roots.

As I grew older, her conversations became more sophisticated, built around themes of political upheavals, broken promises and the realities of being an immigrant woman with two daughters in New York City. By age 13, then, as I discovered the joys of Celia Cruz at apartment parties, I also knew about the works of Jose Martí, a hero of Cuba’s independence — and who Fidel and El Che were. I knew that I had come from people with a history that included struggle and achievements and that I was still part of that evolving history here in the U.S.

There was a power in that knowledge of both sides of me, and more important, an accuracy. My family’s past was preserved for me as a sacred part of who I was, and ultimately, that duality gave me the habit of nuance in considering people and events, a habit I believe I bring to writing children’s books.

Bicultural kids will always need environments that inform both of their realities, not because their families don’t want to let go of the past but because the past informs their current identities.

I want my niece to love reading as much as I do. She doesn’t. Arguments ensue. The experts’ advice? Chill out — kids read differently these days.

Pura Belpré, the noted Afro-Puerto Rican librarian who established bilingual materials in New York public libraries during the Harlem Renaissance, famously railed against the notion that her Black and brown bilingual patrons were “culturally deprived.” She spent her career advocating for a range of materials and approaches that would connect children to their Puerto Rican roots with pride. “A child will be better prepared to understand the value of another culture if he knows the value of his own,” she said.

During the summer, we owe our children some time to heal and reset for the coming year. We also owe them a way to discover books as recreation, connection and affirmation. We owe them stories that celebrate who they are and that offer a way to understand the long tendrils of displacement that last for generations in families.

If we don’t make that effort, we risk allowing inaccuracies, shame and stereotypes to replace the truth.

Meg Medina is the 2019 Newbery medalist. Her forthcoming book is “Merci Suárez Plays It Cool.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.