Op-Ed: They say you shouldn’t meet your heroes — but they weren’t talking about Sandy Koufax

- Share via

Last month, on the day after Father’s Day, my phone rang. Even though the call was from an unknown number, I answered and heard a voice say, “Hi, it’s Sandy Koufax.”

I held my breath in surprise, even though just a few days earlier our lives had briefly intersected.

My journey with Sandy began years ago when I was a young child who idolized him. I was 9 years old when the Brooklyn Dodgers relocated to Los Angeles in 1958. The team brought me such joy while I tried to survive the turbulence of a chaotic home life. I spent many nights with my transistor radio on my bed, keeping score as Vin Scully told the story of the game and of the players themselves — Jackie, Duke, Pee Wee, Don and especially Sandy.

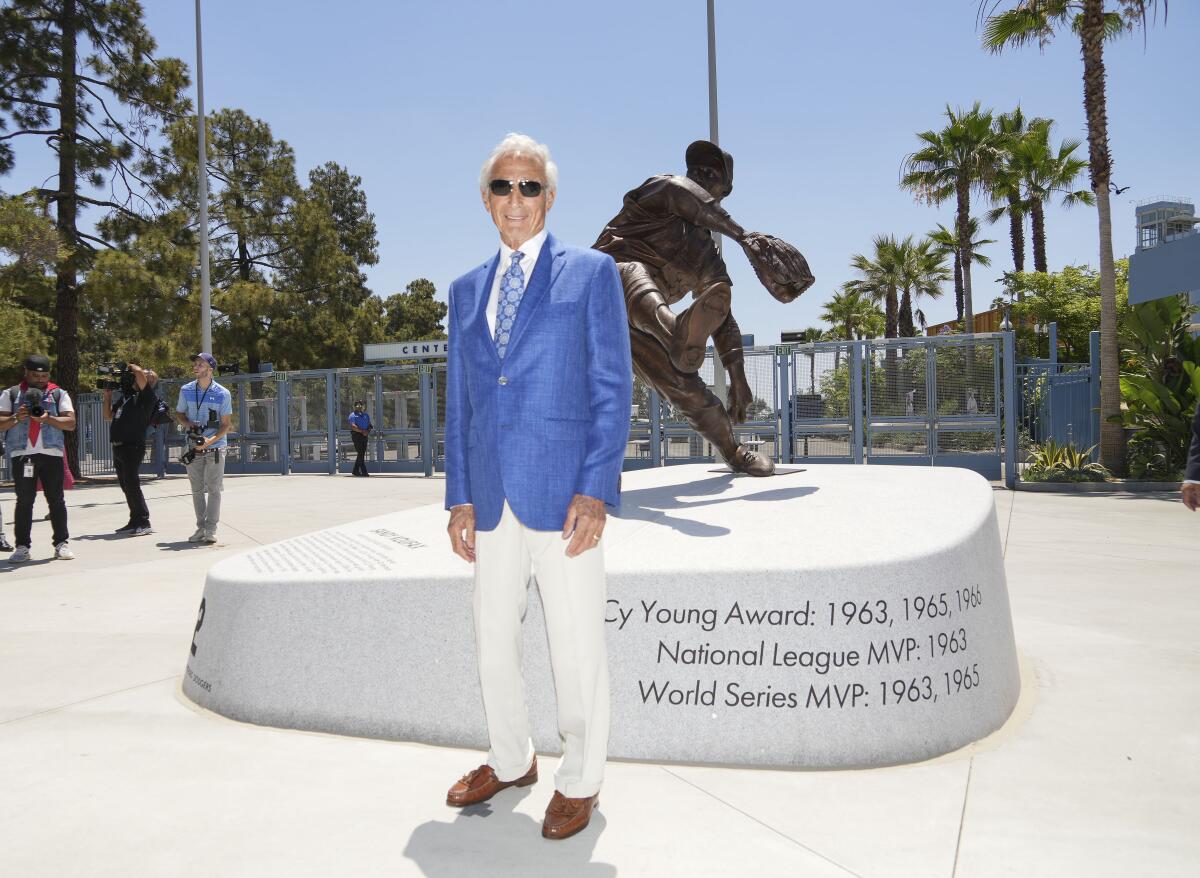

Legendary Dodgers pitcher Sandy Koufax thanks 46 people during a 10-minute speech at the unveiling of his statue at Dodger Stadium on Saturday.

Living in Huntington Park in southeast Los Angeles, I was one of only a few Jews in my high school and I had no Jewish role models or heroes. That all changed when Sandy took the mound. All baseball fans marveled at his extraordinary no-hitters, complete games and strikeouts. I took pride in Sandy because of these accomplishments — and because he was Jewish.

Then came Game 1 of the 1965 World Series, the Dodgers playing the Minnesota Twins. The game fell on the same day as Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, one of the most significant holidays in the Jewish faith. Sandy chose not to pitch. He said of his choice not to play, “A man is entitled to his belief and I believe I should not work on Yom Kippur. It’s as simple as all that...”

Yet this one simple decision created reverberations that continue today. To me and many others, it made him a champion of religious conscience and standing up for one’s beliefs. I believe it is one of the key reasons I pursued a life as a rabbi, seeking justice and doing humanitarian work. Fans often attach large narratives to our heroes, and it does not really matter if those comport with reality, if they help to inspire us and provide us with hope.

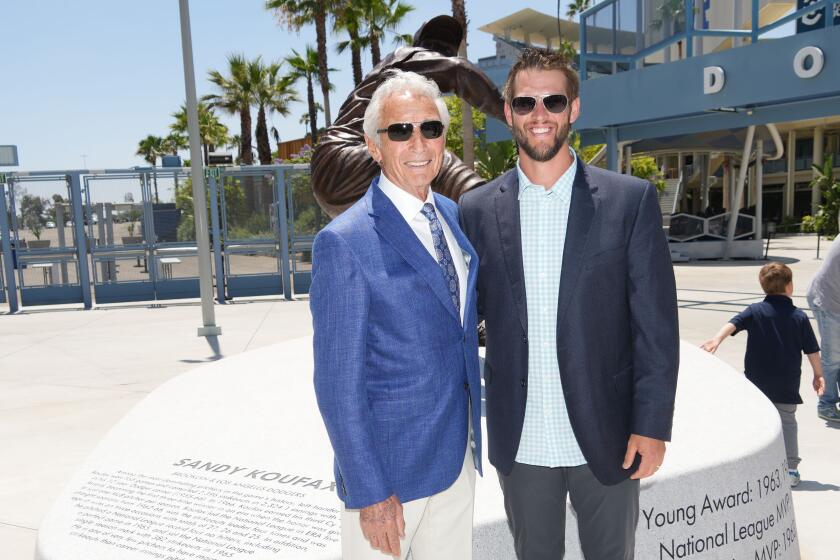

On June 18, my son Micah and I made the pilgrimage from Northern California to L.A. to be present when the Dodgers unveiled the Sandy Koufax statue at Dodger Stadium. At our hotel, we stepped into the elevator and as the doors closed, we realized that Sandy was standing there behind us. At first, I didn’t want to be “that guy” who infringes on the personal space of a famous icon, but then I made myself speak to him, sharing a few overheated expressions of admiration and respect. If Sandy was embarrassed or uninterested, he didn’t show it in his words or his smile. In those few moments, he transformed from my childhood superhero to a real-life person of warmth and integrity.

Later that weekend, we saw Sandy in the hotel restaurant eating breakfast. We did not want to bother him, but we arranged for his meal to be charged to our room and gave the waiter a note to pass along to him. We left Los Angeles feeling delighted that we had treated Sandy Koufax to breakfast.

Then came the phone call. Sandy said he wanted to say thank you and we had a wonderful 10-minute conversation. This simple act speaks to the man we have always believed he is, someone who treats others with respect and tries to do what is right.

His remarks that weekend at the statue unveiling showed the same thing. They were marked with gratitude and celebrated others. Listening to his speech, I finally understood that this intensely private man has a much less complicated view of himself than the one so many of us have projected on him.

I now view Sandy’s decision to not pitch on Yom Kippur differently. It is no longer the grandiose act I had built it up to be. Just like with his phone call, he was simply doing what was right for him and his conscience. He was not trying to be a model of anything bigger.

Viewing Sandy’s actions through this light reinforces for me that the world is transformed not by words and proclamations, nor bold heroic acts, but through everyday acts of thoughtfulness and decency that everyone can do. Those acts, which are central to the human experience, are needed more today than ever before.

Lee Bycel is a rabbi, the vice chair of the California State Council on Developmental Disabilities and the author of “Refugees in America: Stories of Courage, Resilience and Hope.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.