Opinion: Florida’s sea temperature hit 101. What does that mean for the world’s oceans?

- Share via

“Who hears the fishes when they cry?” — Henry David Thoreau

Until I was 15, I thought I was born too soon to explore alien worlds. Then my family visited Key West and I got a mask and snorkel and discovered the alien world of the oceans — living corals and shoaling fish, hammerhead sharks and sea turtles straight out of the age of the dinosaurs. The world’s third largest coral reef transformed my life and opened me to the wonders of the saltier 71% of our planet.

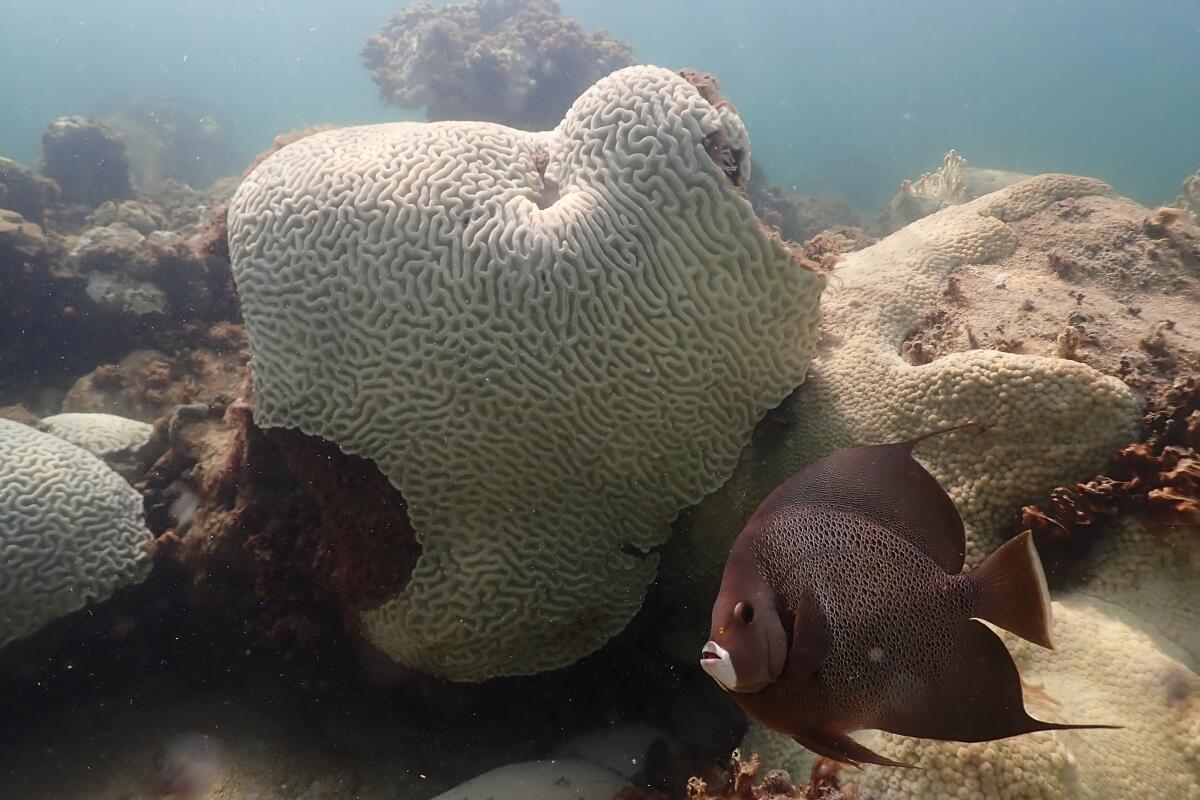

Ocean temperatures around the Florida Keys hit an unprecedented 101.1 degrees this July, resulting in the worst coral bleaching in the reef system’s history. There will also likely be an intensification of this year’s hurricane season due to the hot tub like ocean conditions.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is reporting that 44% of the world’s oceans are experiencing marine heat waves right now, and that figure is expected to pass 50% by September (again, unprecedented). A marine heat wave killed 95% of the kelp off Northern California more than five years ago and little, if any, has recovered.

As climate change heats ocean water around coral reefs, scientists in Florida race to haul coral to safety in gene-bank tanks before they go extinct.

For decades the ocean has masked the worst of the climate emergency by absorbing 90% of the heat and almost one-third of the carbon-dioxide spewed into the atmosphere from the burning of fossil fuels and deforesting of the planet. Now we see the results: changes in the physical nature of the ocean — its temperature, circulation, chemistry and color.

A warming ocean means rising sea levels because of thermal expansion and melting glaciers. Projections of up to 3 feet of sea level rise by the end of the century now seem quaint given NOAA’s latest projections: up to 7 feet, if we continue on our current course of inaction.

A new report in Nature Communications projects that with the melting of Greenland’s glaciers the shutdown of the Atlantic Ocean circulation (known as AMOC) could happen within this century, sometime between 2025 and 2095, resulting in a Northern Hemisphere deep freeze not seen since the last ice age. Even as the planet as a whole overheats.

The sea is rising higher and faster — California could see a jump of more than 9 feet by the end of the century. Flooding and erosion threaten homes. Beaches could vanish. But everyone insists: This is a game that can be won.

Some scientists think the ocean may also have reached a saturation point in its absorption and buffering of carbon dioxide. In the process, the PH of seawater has shifted, creating what is known as ocean acidification, making it harder for shell-forming creatures to extract calcium carbonate out of surrounding saltwater in order to grow. The shellfish industry has become the indicator species for this threat.

And as the ocean becomes warmer and more acidic, it holds less dissolved oxygen, resulting in expanding dead zones in coastal regions (415 in 2022 up from 10 documented in 1960) but also in open ocean mid-water columns, where it’s hampering the largest wildlife migration on the planet — the nightly upwelling of deep ocean creatures that feed at the surface before retreating to avoid daylight predators.

The ocean’s warmer waters are also accelerating diseases and infections among marine wildlife ranging from fish to sea stars to whales. In late July close to 100 pilot whales formed a heart-shaped cluster before stranding and dying (or having to be euthanized) on a beach in Australia.

A July 12 study in Nature found a color shift in 56% of the ocean, with the tropical ocean becoming greener over the last 20 years, reflecting changing organisms in the water likely driven by human-induced climate change. “To actually see it happening for real is not surprising, but frightening,” said one of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology scientists who co-authored the study.

Kelp forests north of the Golden Gate are in dire shape. The return of the sea otter could help bring them back to life.

Cumulatively, the ocean seems to have begun a process of collapse into a simpler more primitive state, similar to that of hundreds of millions of years ago, when high-temperature-low oxygen-tolerant jellies and microbial mats were the dominant forms of marine life.

And as if that weren’t enough, the loss of Arctic Sea ice is resulting in the release of methane from the ocean floor (methane is also leaking from melting tundra on land). Methane is a greenhouse gas 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

I’m more enraged than depressed by all this. We know what the solutions are, but we lack the political will to make the rapid transitions needed, failing to meet commitments made at the 2015 Paris Climate Summit to contain global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius — a threshold that marks the difference between merely dangerous conditions and the catastrophic climate change we’re beginning to experience in our overheated cities and seas. Nor am I hopeful for the next round of U.N. climate negotiations that will take place in Dubai at the end of the year, led by the head of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Co. (a turn of events like something out of the disaster comedy ”Don’t Look Up”).

Our climate challenge now is to do what we can where we can to salvage what we might.

This is where opinion articles are supposed to offer hope. After all, clean energy is now cheaper than fossil fuel. But as noted, we are not moving fast enough. It doesn’t help that the United States has a two-party system in which one party acts as an almost fully owned subsidiary of the fossil fuel industry.

So all I have to offer is triage — saving what we can while we can in the hope there will be enough biodiversity left at the end of this Greenhouse Century to maintain the intricate balance of life on Earth.

One certainty is that the ocean, the crucible of life, driver of climate and weather, and generator of oxygen, no longer has the capacity to absorb the existential danger we have created. The ocean will endure, of course, just not as I knew it as a 15-year-old swimming in a living sea of wonder.

The author Isak Dinesen once wrote, “The cure for anything is salt water — sweat, tears or the sea.” These days I save my tears for the sea.

David Helvarg is a writer, executive director of Blue Frontier, an ocean policy group, and co-host of “Rising Tide: the Ocean Podcast.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.