Opinion: Love the Hollywood Burbank airport? Try living under its flight paths

- Share via

It starts around 6:45 a.m. — a faint, faraway boom, followed by a low growl that makes my stomach tighten and hands clench. Within seconds, the growl turns into a low rumbling, then a loud rumbling, then an intensely loud roar and whine, up to 70 decibels, as a 737 shoots over its low path across the Mulholland Corridor.

This goes on constantly for the next four hours as the planes of Southwest and other airlines fly west from Hollywood Burbank Airport and over Studio City, where I live, and the homes of 200,000 other San Fernando Valley residents, from Toluca Lake to Encino.

In late morning, the frequency of these flights slows down, though they are joined by scores of helicopter flights that follow the same path. About 5:00 p.m., the 737s pick up their pace again, along with extremely low-flying UPS and FedEx jets.

Hollywood Burbank Airport filed a lawsuit seeking to block approval of an environmental report for the California high-speed rail project.

This goes on until about 10 p.m., when the celebrity and business flights enter the narrow airspace in droves, jetting to and from Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, or even Anaheim or Santa Monica. Things die down after 11 p.m., when only the occasional American or JetBlue flight makes a connection, or when Jay-Z needs to head out to a meeting in New York.

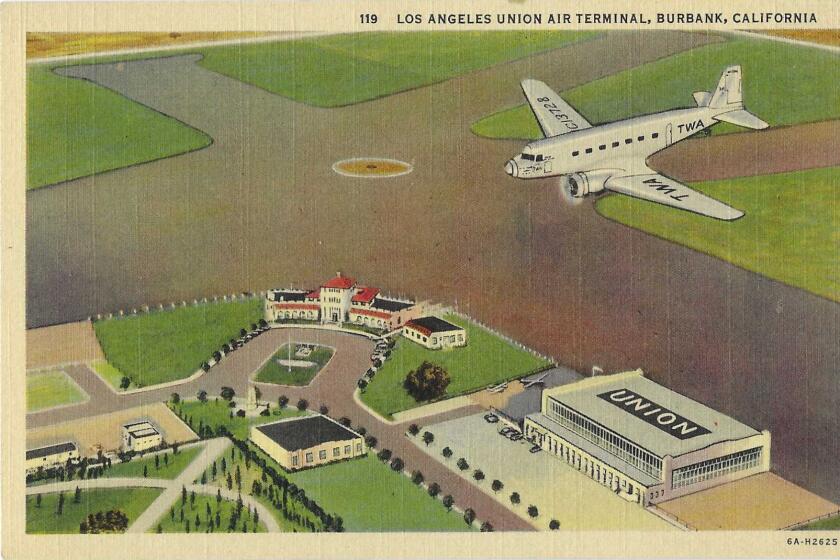

For many Angelenos, the Burbank airport is a well-loved throwback alternative to LAX. But seven years ago, a sudden shift in flight patterns allowed more flights and forced more of them south of the 101 Freeway. Those of us living under the changed flight paths now contend with a new level of daily noise, air pollution, and huge amounts of black plane soot in our yards, trees and plants.

We still have lots of airfields, but gone from the landscape are the runways — near Griffith Park, near Wilshire and Western, in the Palisades — that could have challenged LAX for air superiority.

Several activist groups have labeled this jet superhighway a “sacrifice zone” — a place where others profit off residents’ health and safety degradations. An estimated 10,000 schoolchildren live and study under this jet superhighway, which also spans 75,000 acres of Santa Monica Mountains parkland that is home to a dwindling wildlife population and draws hikers and others from all over Southern California.

How did a part of Los Angeles that is both densely populated and contains legally protected green space become a dumping ground for jet fuel soot and dangerous levels of noise pollution?

In late 2016, the Federal Aviation Administration shifted flight paths south ostensibly to save fuel and modernize its flight procedures. Most communities deeply affected by this shift did not know about the change until it was too late for residents to file petitions or protest. One day in the winter of that year, several jets in rapid succession flew so low over our home that we thought there was military action nearby. Seven years later, 100 to 200 flights per day go directly or nearly directly over my home.

Community group UproarLA provided the Southern San Fernando Valley Airplane Noise Task Force with its solution on how to address airplane noise in the region.

At the time of the change, this swath of land was represented by some of the most vocal environmental champions in Los Angeles — City Councilmembers Paul Krekorian and Paul Koretz.

They, as well as a representative from then-Sen. Kamala Harris’ office, attended meetings with the public about the new flight paths and formal task force meetings with the public and the FAA from September 2019 to May 2020. Former Los Angeles City Atty. Mike Feuer and the current City Atty. Hydee Feldstein-Soto have filed lawsuits against the FAA over the shift in flight patterns and the proposed airport terminal expansion, respectively. But those legal actions have not stopped the FAA.

Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) has asked the FAA for a review of noise around the airport, and Rep. Brad Sherman (D-Sherman Oaks) wants the project halted until the FAA can reduce the noise and environmental impacts on the community. But the FAA informed Sherman that the recommendations made by the task force didn’t meet federal safety criteria. The agency recently issued a draft Environmental Assessment on the proposed changes to the airport’s southern departures. The public can submit comments until Jan. 24.

Meanwhile, the airport is growing, with more flights now than in 2016. The airport’s proposed expansion of its NextGen satellite system, an upgrade to one of its terminals and a change in airport configuration will almost certainly bring even more flights and more noise to the Mulholland Corridor. The airport will also be using federal funds designated for its terminal expansion in litigation involving the project, which Sherman opposes.

Who benefits from a larger, busier airport and this flight path? Southwest and other airlines, which boost the tax revenue for the city of Burbank. No single community should have to bear the brunt of the airport’s noise and environmental impact. The airport should fairly disperse the flights and revert to higher altitudes.

Los Angeles city and county leaders, the state’s Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy and the Mountains Recreation and Conservation Authority all have a stake in the impacts caused by the Burbank airport. They may be the only people able to bring the federal regulators to the table. Meanwhile, my neighbors and I, as well as the animals and plants of the Santa Monica Mountains, are suffering.

Julia Bricklin, an author and historian, lives in Studio City. This article was produced in partnership with Zócalo Public Square.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.