Opinion: Should California schools stick to phonics-based reading ‘science’? It’s not so simple

- Share via

A child’s individual differences, skills and experience matter a lot in the learning process, and learning to read is no exception. That’s why new legislation based on the erroneous assumption that there is only one way to teach reading is so dangerous for California’s students. Although well-intentioned, the measure would prevent teachers from addressing children’s diverse learning needs and lead to even more illiteracy.

Introduced by Assemblywoman Blanca Rubio (D-Baldwin Park) with the support of several advocacy groups, Assembly Bill 2222 would strictly limit approaches to language and literacy instruction from kindergarten through eighth grade. It would also limit the type of training and resources available to educators.

Despite its flaws, AB 2222 is written in persuasive terms, promoting a curriculum based on the “science of reading” and prohibiting all other ways of teaching the subject. Who would argue with following the science?

A Stanford study finds that 75 schools using more phonics-based instruction are seeing real results. There should be no more delay in bringing this to all students.

In fact, the term “science of reading” lacks a clear definition. It’s more a misleading marketing ploy and ideological catchphrase than a subset of research or teaching methodology. Consequently, reading experts are concerned about the way such policies are being implemented in schools.

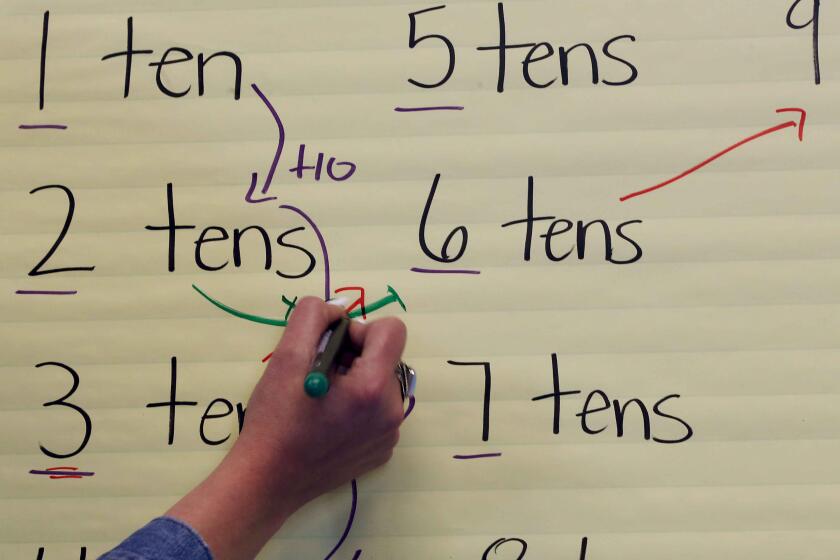

Researchers agree that learning to read is a complex process. But curricula that claim to be aligned with the science of reading tend to oversimplify the process, overemphasize and isolate foundational skills such as phonics (the correlation between letters and sounds), overlook oral language as a foundation for reading and ignore the importance of writing. In other words, they misrepresent the “science” part of the “science of reading.”

Learning to read in this way would be like learning to pedal on a stationary bicycle and then being expected to ride a bike through L.A. traffic without understanding balance, steering, speed and the rules of the road. Some kids — especially more affluent ones — will already have some of those additional skills, but many others will not.

L.A. Unified officials need to explain to parents why they slashed Primary Promise, a program that has helped struggling students improve their reading and math achievement.

Overemphasizing foundational skills can take classroom time away from writing, language development, science and social studies. Foundational skills are extremely important for young students, but they are insufficient for developing critical thinking, reading and writing. When schools put too much focus on basic skills, family wealth and background play an even greater role in education, increasing inequity.

As a former bilingual teacher in a largely Spanish-speaking community, I am particularly concerned about the implications of AB 2222 for English learners. Researchers and educators on all sides of the so-called reading wars agree that English learners need additional support specifically designed for language development, the process of learning how to understand language and use it to communicate.

Approaches characterized as following the “science of reading” tend to overlook the needs of English learners. They might learn to decode words, but if they are prevented from building enough background knowledge through science and other subjects, they will be limited in their comprehension — the purpose of reading.

Researchers have called for greater attention to linguistic and societal factors for bilingual learners in literacy instruction. This is particularly important in California, where 19% of students are classified as English learners and 40% speak a language other than English at home. That suggests this legislation ignores the needs of a substantial share of California’s students.

Literacy teaching certainly needs improvement in California, which has one of the nation’s highest illiteracy rates. But mandating one curriculum is the opposite of what we should be doing to address that. Instead, we should prepare our teachers better and provide research-based, differentiated continuing-learning and coaching opportunities, which has been proved to be an effective strategy. We should provide more rather than less support for our educators to meet the diverse needs of individual students regardless of their home language.

Limiting teachers’ ability to use an array of strategies will only make it harder for them to learn to teach kids who might struggle to learn to read and write. Why would we do that?

While learning language is innate for humans, literacy is not. Governed by cultural and sometimes seemingly arbitrary rules, literacy is difficult to learn and to teach well. Pretending otherwise won’t help anyone learn to read.

Allison Briceño is an associate professor at San Jose State’s Connie L. Lurie College of Education, an editor at the Reading Teacher and a Public Voices fellow with the OpEd Project.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.