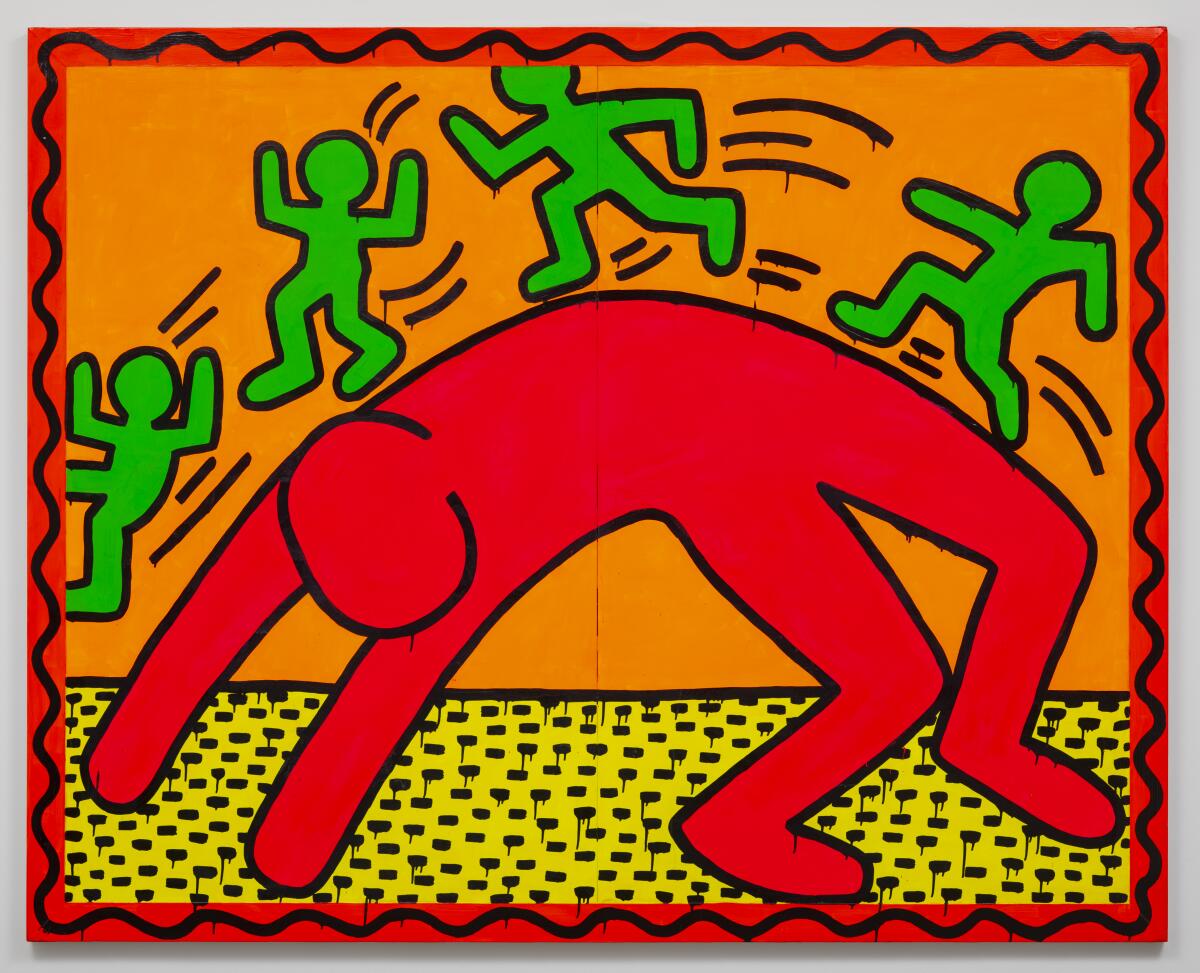

How Keith Haring’s art transcended critics, bigotry and a merciless virus

- Share via

Book Review

Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring

By Brad Gooch

HarperCollins: 512 pages, $40

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

I began reading Brad Gooch’s biography of Keith Haring with the last chapter, on Haring’s untimely death from AIDS. I don’t usually read biographies out of order, but since I (like many) knew all too well how Haring died, I hoped I might learn something different by finishing at a point when the artist was still alive.

Luckily, you don’t have to read “Radiant” backward to get to know the living Haring. Gooch, the author of sensitive biographies of Flannery O’Connor and Frank O’Hara, made it his mission to show how much living and creating Haring packed into just 31 years, and he more than succeeds. “Radiant” not only gives us a much-overdue appreciation of Haring as an important artist. It also paints an exhilarating portrait of a young artist finding himself and his calling.

The writer’s ambitious approach to the historical novel uses techniques reminiscent of “The Handmaid’s Tale” to examine the shifting meaning of freedom.

From the moment he was old enough to hold a pencil, Haring learned to draw from his father and a Disney drawing book, making Mickey Mouse out of two circles. He always made art. The question, for him, was what for? His parents suggested he become a commercial artist. But once he discovered Robert Henri’s book “The Art Spirit,” Haring knew he wasn’t interested in “art as a means of making a living” but rather, as Henri writes, “as a means of living a life.”

Haring found his home at New York’s School of Visual Arts, where he enrolled in 1978. “It was like landing in a candy store, or better,” he wrote in his journal, “a gay Disneyland.” A friend remembered that Haring struggled to stay “within the confines of his classes. You couldn’t open a broom closet that he hadn’t painted or transformed.”

Matt Lodder’s “Painted People: 5,000 Years of Tattooed History from Sailors and Socialites to Mummies and Kings” is a lively exploration of an underexamined art.

One day during this period, Haring noticed an “empty panel covered in soft black matte paper on a station wall” in the subway, and the rest, as they say, is history. “Within the next five years, he would make more than five thousand chalk drawings throughout New York City’s five boroughs,” Gooch writes, “realizing one of the largest public art projects ever conceived.”

Gooch draws on Haring’s prolific journals, which reveal a passionate but pragmatic young artist. Eerily, even on his 24th birthday, Haring seemed to sense his future iconic status. “Today I am 24 years old. 24 years is not a very long time, and then again it is enough time,” Haring wrote. “I have added many things to the world. ... I know, as I am making these things, that they are ‘real’ things, maybe more ‘real’ than me, because they will stay here when I go.”

It was the year Haring turned 24, 1982, that a syndrome called GRID, or “gay-related immune deficiency,” was first reported. By the next year, Haring was showing the first symptoms of HIV infection.

1982 also found the artist busy with his first gallery show, at which a quarter-million dollars’ worth of his work was sold and Andy Warhol stopped by. Warhol would go on to take Haring, along with Jean-Michel Basquiat, under his legendary wing. Not every young artist gets to be mentored by their still-living hero: Haring considered Warhol “the most important artist since Picasso.”

Gooch, “as a poet and fiction writer, also young and living downtown at the time,” obviously has a great personal attachment to and understanding of Haring and his art. His chronicle of Haring’s volcanic rise is deeply engaged with the culture of the time and place — not only the art world but also the gay community and New York. But at its heart, “Radiant” is the story of a young artist grappling with the drive to create and the challenges of commercial success.

And there could be little doubt of Haring’s fame once he found himself competing with his friend Madonna for men. Even Warhol acknowledged in his diary that he was jealous.

Perhaps Gooch’s most important contribution as a biographer is to solidify Haring’s reputation as a serious political artist. After Ronald Reagan’s election, Haring depicted him as a figure “with a TV head, waving an American flag. ... He has a cross in his hand. In the other hand, he has missiles.”

Haring’s drawings of penises and gay sex were, as Gooch rightly has it, “automatically political” for the era. “Keith was heroic in having gay content in his work,” poet John Giorno said, at a time “when we all know that being a gay artist is the kiss of death.” Haring memorably advocated safe sex during the AIDS epidemic, with images of condoms and messages such as “Safe Sex or No Sex.”

While modern audiences might be more likely to understand the import of these themes, many critics at the time discounted Haring’s work as “fast food,” as one put it, adding, “It’s a good time, it’s boogieing on a Saturday night, it’s alive, but great, no.” One curator blamed Haring’s commercial appeal for the reluctance to take his art seriously, saying, “I think Haring was so successful that other artists could not forgive him.” Gallerist Jeffrey Deitch pointed out that most artists enjoying Haring’s level of financial success would have been churning out even more sellable work. But Haring was committed to public projects such as murals, which he did for little or no compensation.

In 1987, during a period of extensive travel, Haring noticed that he was short of breath. The following year, while in Tokyo, he discovered a small purple spot on his leg that, when he returned to New York, was confirmed as Kaposi’s sarcoma. Haring told almost no one of his diagnosis in July 1988. In August, Basquiat died of a heroin overdose at 27. Writer Glenn O’Brien had once asked Basquiat who his favorite painter of his own generation was. “He didn’t hesitate, but said, ‘Keith Haring.’”

When Haring’s lover, Juan Dubose, died of AIDS, the artist said, “I now call our friends, and it’s very hard, because my telling them that Juan had died of AIDS is the same as telling them that I’m going to die of AIDS. I hadn’t even told my parents that I was sick yet, and I had to tell them about Juan.”

Haring told journalists that he was afraid only of no longer being able to work. “That’s the point that I’m at now, not knowing where it stops, but knowing how important it is to do it now.” Later, he would write, “Artists are never really ready to die.” He was going to the studio and working as usual two weeks before he died. Gooch describes his subject’s death with intention: “Keith Haring lived until 4:40 a.m. on February 16, 1990.”

We all die; Haring lived as fully as he could for as long as he could. The tragedy is undeniable, but so is the triumph of Haring’s art, advocacy and public spirit. Gooch’s “Radiant” has given us a more vibrant and complete picture of the enduring gifts of Keith Haring’s life.

Jessica Ferri is the owner of Womb House Books and the author, most recently, of “Silent Cities San Francisco.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.