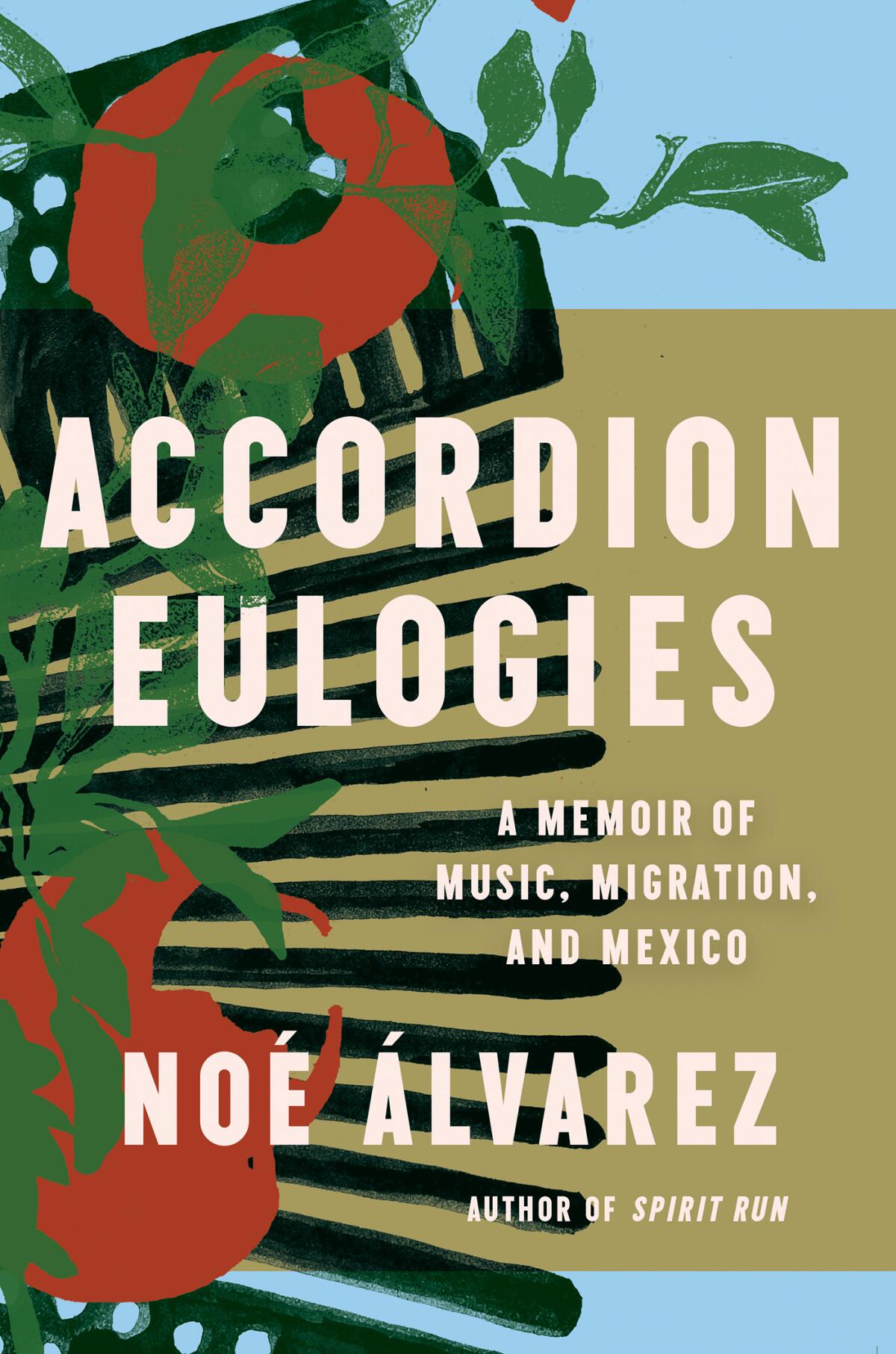

In the working-class desert odyssey ‘Accordion Eulogies,’ Noé Álvarez searches for his grandfather

- Share via

Book Review

Accordion Eulogies: A Memoir of Music, Migration, and Mexico

By Noé Álvarez

Catapult: 208 pages, $26

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

As a child, Noé Álvarez “wandered the orchards under the spell of corridistas — musicians whose spitfire fingers flew over their three-row accordion keys,” he writes in his memoir, “Accordion Eulogies.” “Música norteña — a genre that originated in northern Mexico — gave voice to the disempowered men and women of Yakima who lived and labored apart from their motherland.” The corridos, whose name is derived from the Spanish for “to run,” tell stories of those far from home, on the run, migrating for work or bandits evading capture. Passed down through generations, their stories are a way of preserving history but also a reminder of the place whence you’ve come.

Álvarez, the son of Mexican immigrants, grew up in Yakima Valley, Wash., a semi-arid, now irrigated, area some 200 miles east of Mt. Rainier. His parents worked in the vast apple orchards and listened to the corridos on their radios, comforted by them as they toiled tending to the trees. While the songs eased some of his parents’ saudade, for Álvarez, they were also a reminder of his mythological grandfather who had deserted his family: “a homewrecker, a drunk, a gambler; a man forever caught in the currents of migration.” He was also an accordion player.

Álvarez sets out to find him. What follows is an extraordinary intertwining of fibers in which the hemp of history, music, memories and community knowledge ropes him to the man who left him behind as a child. Álvarez hopes for resolution to the inherited trauma of those forced to wander the land in search of work and the devastation left behind for those who stayed.

Searching for his abuelo also means searching for his instrument. The accordion had its origins in Germany, but was carried into North and South America by immigrants. In Louisiana, Álvarez hears its sounds in a land of the displaced “German, Irish, French, French Canadian, Native American, Anglo American, Italian, and Spanish” who landed there. Black Creole elders created forms of music that spoke to their descendants. Zydeco — music with a snappy beat that derives its name from French Creole colloquial expressions for poverty and tough times — is powered by the accordion. Álvarez meets zydeco legend Jeffery Broussard, “a bruised man with a story to tell.” A hard life as a Louisiana Black man has prepared Broussard to use his accordion to help folks with healing zydeco traditions.

Asante’s layered voice creates its own rhythm and flow, as he weaves a personal story with reflections on Black American history.

Broussard tells him, “It’s music that holds a lot of sadness … that also finds comedy in tragedy, tackling themes that are relatable to the local populations.” The Black Creoles carried the scars of slavery, and they infused their music with African and Haitian song, using call and response songs that “made music with their beaten bodies, never relinquishing the sounds of their homelands.” The accordion added its rich sound to this mix.

Similar stories emerge in other parts of the United States, where accordions took hold on the West Coast and in the Midwest, the South and Texas, where Álvarez journeys next. There he meets an accordion builder, who spends more than 100 hours handcrafting each instrument.

Álvarez reaches out to an Italian accordion player, who initially rejected the instrument for its status as working-class folk music. On a trip to Ireland, Álvarez meets a musician who lives in a country emptied out in waves as poverty, famine, political oppression and violence scattered its people. But it’s not all sadness. The Irishman tells him that “words can sometimes fail us, melody can save us. It can give you back your color, give you back your feelings, and give back the stories that migrants lose on dangerous pilgrimages.”

José Vadi’s “Chipped: Writing From a Skateboarder’s Lens” is a granular but accessible look at the practice and subculture of the sport.

As a sound carried by those who do the backbreaking labor of building and harvesting crops, work seen as undesirable by the middle class, accordion music is rich with history but also permeated by a fraught masculinity. What does it mean to be a “provider” if work carries you miles away from your family? Álvarez’s grandfather fled, a man chasing a dream of “something more” that he could not find even thousands of miles from his Mexican village.

Álvarez recalls a childhood where educators prohibited him from speaking Spanish in school, thus he was forced to learn a language of the people who relied on migrant labor but were resentful of those they employed. As an Indigenous Mexican, he recalls the irony of being prevented from speaking the language that was imported by those who had conquered the land and decimated its people.

In Mexico, Álvarez experiences the double bind of the American Mexican. Seen as American — and not to be trusted — by those who stayed, he becomes a man whose sense of identity is put to a severe test. He is personally affected by drug cartel violence, and the dangerous landscape leads him to a greater understanding of what made his family leave.

The publishing world has been unfriendly to writers of color. In her new novel, Alvarez demands we hear the stories that don’t make it to print.

“Accordion Eulogies” is a working-class desert odyssey that ends in the home of Álvarez’s abuelo. For years, the only reminder Álvarez had of him was a photo of a younger man holding an accordion. Tied together by their shared history of music, and their magical beliefs that what they’re looking for is lying in their next destination, the two men finally meet.

Most of us living in the U.S. are the descendants of those who fled their homelands because of the constant violence of poverty, hunger and lack of opportunity. For those who are several generations away from those experiences, the pain of leaving is long forgotten. But for the children of recent immigrants, the double consciousness of feeling set apart in America while being an alien in our ancestral lands is an ache hard to articulate.

But with “Accordion Eulogies” Álvarez has written his own corrido, creating a harmony from these difficult, sometimes unspeakable, themes. In finding connection through the accordion — originally brought from far away but now the instrumental repository of a million immigrant stories — he has composed a classic melody.

Lorraine Berry is a writer and critic in Eugene, Ore.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.