One year later, Democrats try to use painful lessons of 2016 to guide future campaigns

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — As hordes of progressives make plans to scream helplessly at the sky Wednesday to protest the one-year anniversary of Donald Trump’s election, the influential Democrats whose strategic missteps and disconnectedness to the electorate helped deliver his victory have other plans.

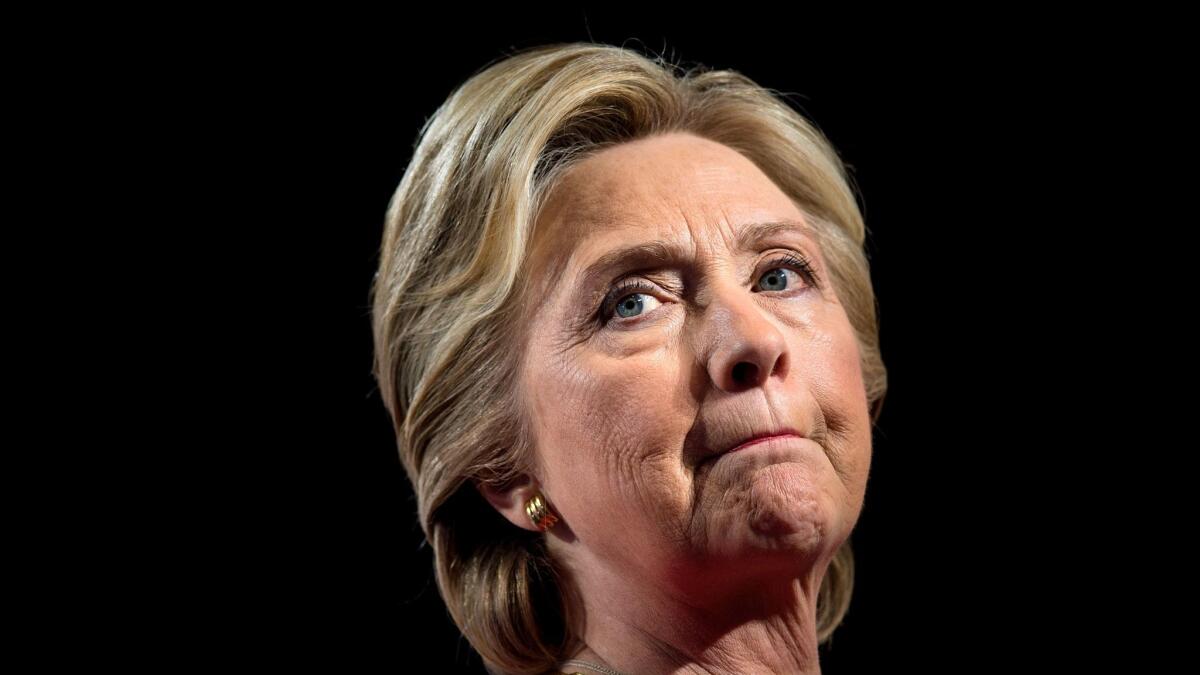

The operatives and donors who propelled Hillary Clinton’s campaign are combing ever deeper through the painful details of an election gone terribly wrong for Democrats as they determinedly try to correct course. They are seizing on the clarity that comes with distance to plunge into difficult discussions about what might have been done differently – and how they can put those lessons to use in upcoming elections.

The longtime Clinton confidant who was the chief strategist for her $190 million super PAC says he still loses sleep over his failure to more effectively frame Trump’s history of misbehaving. The liberal California billionaire activist who built his fortune mining data points to the loss as a lesson in the shortcomings of campaigning by algorithm. The think-tank president who has long advised Clinton on policy now regrets how dismissive Democrats were of Trump’s grasp of the issues.

The refocusing is driven by reams of election autopsies, many making use of modern tech tools to pinpoint with impressive precision how steep the cost was of each false move the Clinton campaign made and how badly the campaign missed the pulse of an electorate yearning to shake things up.

Whether the Democrats can find that pulse again will start to become clear Tuesday when voters in New Jersey and Virginia elect new governors and will become clearer still in the midterm congressional elections a year from now. The stinging 2016 loss is informing the way each one of those campaigns is run and the intense debate among Democrats about the path forward.

A fresh round of reports from data crunchers and focus group conveners has emerged as the election anniversary arrives. Each reveals that the fatal wounds to the Clinton campaign did not come exclusively from former FBI Director James Comey’s 11th hour revelations about his probe into Clinton’s email servers or the malfeasance of Russian hackers. Many were self-inflicted.

“I am still kicking myself three times a day,” said Paul Begala, a longtime advisor to both Bill and Hillary Clinton who directed strategy for the super PAC Priorities USA. “We should have won… I continue to lose sleep over this. I’ve never before lost sleep over an election in my life.”

Gnawing at Begala most are the ads that his organization aired that attacked Trump’s character but, he now says, failed to spell out for voters why it would affect them. His regrets track the same broad theme recounted by other Clinton operatives: strategy was guided too much by the numbers, by past voter behavior, by coastal sensibilities of what would resonate.

“If you are a single mom in Dayton, Ohio, how does it affect your life that he brags about grabbing women by their privates or ridiculing a person with a disability?” Begala said. “I did not link it back up like we did when we went after Mitt Romney,” he said, referring to the Republican presidential nominee in 2012. “We attacked Romney’s business record and said, ‘He did this to working people in Indiana and will do it to you.’”

Democrats are also reckoning with how they misjudged boasts and false promises from Trump that they assumed would do him in, like his vow to reopen mines in Pennsylvania that were flooded decades ago and are not possible to operate or to provide cheaper, better healthcare for everyone or to slap massive tariffs on all Chinese imports.

The simple ideas – unrealistic as they may have been – connected with voters more than the fully baked volumes of policy plans Clinton proposed.

“It is a misunderstanding to say he had no policies,” said Neera Tanden, a longtime Clinton policy advisor and president of the Center for American Progress, a liberal research and activist group. “He was able to communicate to working-class people that he was concerned about their plight.”

Future Democratic candidates, Tanden said, should learn from the way the party failed to communicate last year with Rust Belt workers well into middle age. Those voters heard from Trump that he was determined to stop jobs from moving out of the country. From the Clinton campaign, they heard talk of college affordability and raising the minimum wage.

“If you are making $25 an hour, but worried jobs would disappear, one of those messages is more immediate,” Tanden said.

Democrats are still struggling to adjust. Their efforts are being helped along by Trump, who hasn’t delivered on the big initiatives he promised – and now has a record in office that makes some economically stressed, working-class voters anxious. Trump’s support among swing voters and Obama supporters who defected to his side has declined slowly, but steadily all year.

Still, Democrats worry that relying on public uneasiness with Trump to win future elections would just repeat the mistake the party made last year.

“When you look at long-term successful political parties and movements, there is a message that is powerful and inspirational for people you are trying to reach,” said Tom Steyer, the California billionaire and Democratic activist. “If you look at the last few years in the Democratic Party, one of the questions legitimately is, ‘Is there a cohesive vision of what we are trying to accomplish?’”

As Democrats try to overcome their messaging problem, they also confront a challenging operational one. Even Steyer, who made his hedge-fund fortune with the help of sophisticated data analytics, is troubled by how exclusively the Clinton campaign relied on such technology.

Donnie Fowler, the political strategist and Silicon Valley technologist who ran the Democratic National Committee’s get-out-the-vote operation for Clinton, is still haunted by last year. Fowler’s autopsy of the loss has been a must-read for Democrats. Among other things, he found that the campaign was so confident of its computer model showing an impenetrable blue wall of support in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania that it disregarded pleas from organizers in those states to send more resources.

“The warning signs were there,” he said. “There was a tremendous amount of concern by a lot of veterans in the states.” Local organizers kept reporting that on-the-ground efforts did not come close to matching what had happened during the Obama campaigns, and Clinton’s Brooklyn headquarters undermined their efforts by being reluctant to give state organizers the authority they needed, he said.

Campaign headquarters was “flying in a fog of their making,” he said. “Even if it were a brilliant model built by the best data scientists in the country, they shouldn’t have relied only on it.”

The cost of such miscalculations has become clearer with each new report. The decline in black turnout and support compared with Obama’s last election, for example, was enough to sink Clinton in the key states on which the outcome turned, according to a new analysis from the Center for American Progress. While matching Obama’s historic support among African Americans was unlikely, the declines Democrats experienced proved fatal when combined with Clinton’s loss of support from whites without a college education.

Democrats are pivoting their strategies as research from the center and others shows that the white, working-class vote is larger and more influential than the party’s operatives seemed to accept during the campaign. Whites without a college education made up 45% of the vote last year, the center’s analysis estimates, a considerably larger share than indicated by exit polls.

Many Democratic activists “don’t get that this is still in very important ways a white, non-college country,” said Ruy Teixeira, one of the study’s authors. Progressive operatives tend to live in areas where most people have gone to college, he noted.

“Geographic segregation really skews people’s perceptions of the country they live in,” he said.

There was another a big problem the Clinton campaign couldn’t do much about: Voters perceived her as the establishment. Among the many voters who disliked both her and Trump, most broke toward him in the end, analysts poring through polling data have found. Democrats are quick to point out now that Republicans control everything in Washington, hoping that voters’ continued anti-establishment fervor will be the GOP’s problem now.

But last year’s election made clear that exploiting the desire for change requires a different playbook, one that involves paying more attention to what voters are thinking, instead of what a computer model predicts they should think.

It’s a point not lost on EMILY’s List, the fundraising behemoth for liberal women in politics, where president Stephanie Schriock is trying to apply the lessons learned from last year into mobilizing the record 20,000 women who have sought the group’s guidance and resources since Trump’s victory.

“There’s a real commitment to better figuring out where people are,” she said.

Follow me: @evanhalper

ALSO

Virginia tests a likely 2018 election strategy: Racially fraught appeals

GOP House tax bill would deliver blow to California homeowners

Charges in the Russia investigation so far

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.