As WikiLeaks’ Julian Assange faces new U.S. charges, some worry about threat to press freedoms

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — Julian Assange, the founder of WikiLeaks and a thorn in the side of intelligence agencies, faces 17 additional U.S. criminal charges under the Espionage Act, according to an indictment released Thursday, a step that 1st Amendment advocates warned could set a precedent for far-reaching restrictions on press freedoms.

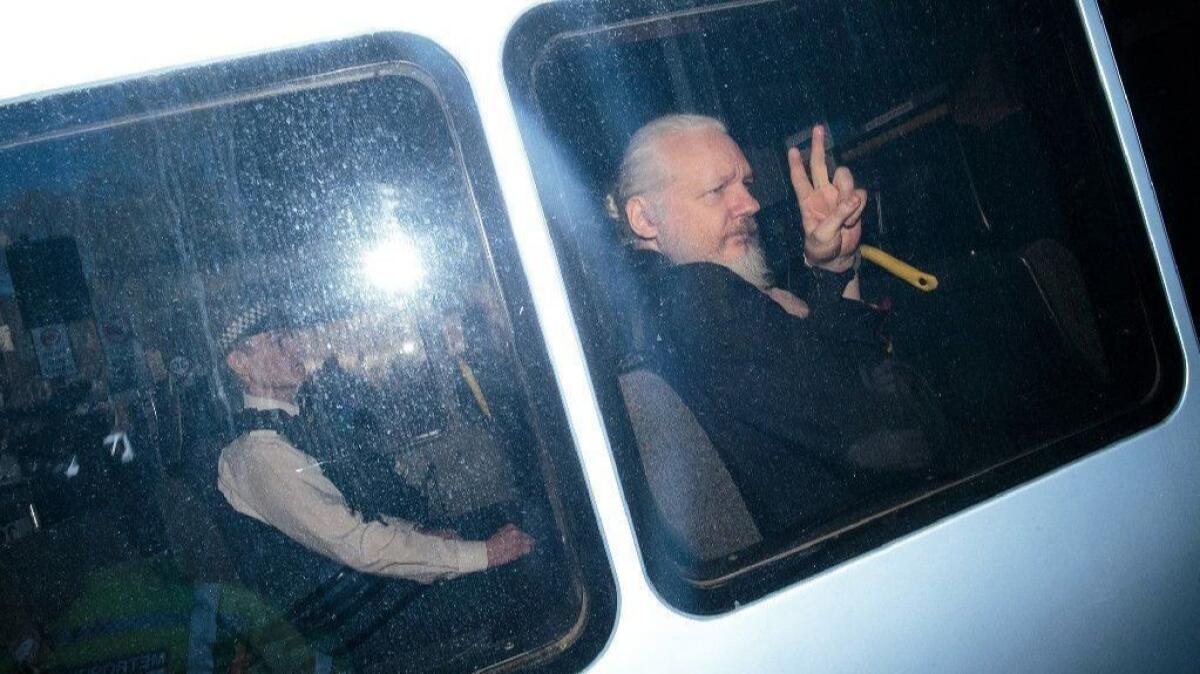

British police removed Assange, 47, on April 11 from the Ecuadorian Embassy in London, where he had sought refuge seven years ago to avoid prosecution in Sweden in an unrelated sexual assault case.

At that time, prosecutors charged him with conspiracy to hack into a Pentagon computer network by allegedly offering to help Chelsea Manning, then a U.S. Army intelligence analyst in Iraq, with cracking a password in 2010. Manning ultimately provided WikiLeaks, an online organization that collects and disperses sensitive records, with hundreds of thousands of classified documents, including State Department cables and reports on fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan.

By contrast, the new charges allege that Assange, who is currently fighting extradition to the U.S., unlawfully obtained and disclosed national defense information in violation of the Espionage Act.

That law was originally enacted to crack down on spying during World War I, but it has been increasingly used to target people who leak classified documents. It has never been used against a person for publishing national security information.

The new charges will reignite the debate over Assange’s claim that he is a publisher like any other and broader issues of how far the press can go in publishing government secrets. News organizations routinely encourage sources to provide them with highly sensitive information, and publication of even secret material has been considered shielded by the 1st Amendment’s protection of freedom of the press.

The Obama administration aggressively prosecuted leakers, but Justice Department officials decided not to charge Assange under the Espionage Act because of concerns about the 1st Amendment. The Trump administration signaled early on that it planned to reconsider that issue.

The decision to move ahead with the prosecution comes against a background of tense relations between the administration and news organizations, which Trump has often referred to as “enemies of the people,” and amid an escalating effort to crack down on government officials who provide information to reporters.

“This is an extraordinary escalation of the Trump administration’s attacks on journalism, and a direct assault on the 1st Amendment. It establishes a dangerous precedent that can be used to target all news organizations that hold the government accountable by publishing its secrets,” said Ben Wizner, director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s Speech, Privacy and Technology Project.

WikiLeaks gave a more pungent response.

“This is madness,” the group said on Twitter. “It is the end of national security journalism and the 1st Amendment.”

John Demers, the Justice Department’s top national security official, defended the decision to prosecute.

“Some say Assange is a journalist and he should be immune from prosecution for these actions,” he said. “The department takes seriously the role of journalists in our democracy. It is not and has never been the department’s policy to target them for reporting.”

But, Demers added, “Julian Assange is no journalist. This is made plain by the totality of his conduct as alleged in the indictment.”

Bruce Brown, executive director of the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, said in a statement that the government’s insistence that Assange is not a journalist doesn’t remove the threat to those who are.

“Any government use of the Espionage Act to criminalize the receipt and publication of classified information poses a dire threat to journalists seeking to publish such information in the public interest, irrespective of the Justice Department’s assertion that Assange is not a journalist,” he said.

If Assange is successfully extradited, he will face trial in the Eastern District of Virginia. Each new charge carries a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison.

Zachary Terwilliger, the U.S. attorney there, said Assange’s disclosure of sensitive information jeopardized human sources relied on by U.S. diplomats and intelligence officials in Syria, Iraq, Iran, China and Afghanistan.

“Assange knew his publication of these sources would endanger them,” Terwilliger said. “He is not charged simply because he is a publisher.”

The indictment said Assange in 2009 released a list of his organization’s “Most Wanted Leaks” to encourage people to provide military and intelligence documents.

Manning appears to have responded to Assange’s public solicitation, the indictment said, searching the classified Pentagon network for some of the same terms highlighted by WikiLeaks, such as “interrogation videos.”

Who is Julian Assange? Arrest of WikiLeaks founder spotlights a showy yet enigmatic figure »

“Assange knew, understood, and fully anticipated that Manning was taking and illegally providing WikiLeaks with classified records containing national defense information of the United States,” the indictment said.

The indictment said Assange was warned by a State Department legal advisor that publication of some documents could endanger people, something he allegedly acknowledged in a media interview at the time.

“We are not obligated to protect other people’s sources,” Assange said during an event in 2010.

After Manning began providing classified records to WikiLeaks, Assange encouraged her to provide more, according to the indictment. At one point he sent her a message saying “curious eyes never run dry,” and Manning downloaded more files to provide to WikiLeaks, the indictment said.

The documents involved the military’s rules of engagement, and the indictment said the disclosure “would allow enemy forces in Iraq and elsewhere to anticipate certain actions or responses by U.S. armed forces and to carry out more effective attacks,” according to the indictment.

Manning was prosecuted for leaking the documents to WikiLeaks, and she was sentenced to 35 years in prison. President Obama commuted her sentence before leaving office, and she ultimately served seven years from the date of her initial arrest.

She is currently in custody after being jailed this year for a second time for refusing to cooperate with a federal grand jury investigation related to WikiLeaks.

Assange faces more legal problems in Sweden, where authorities have reopened a sexual assault case against him. That investigation began in 2010, which led Assange to take refuge in the Ecuadorian Embassy to avoid extradition to the country.

WikiLeaks also played a key role in Moscow’s covert operation to influence the 2016 election. Russian military intelligence officers hacked Democratic Party emails and provided them to WikiLeaks, which later released them at key moments during the campaign.

Assange has not been charged in connection with that case.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.