Mitt Romney appears a shoo-in for Utah’s Senate seat. The question is how he’d handle Trump

- Share via

Reporting from Lehi, Utah — In all likelihood, Utah will have a new U.S. senator next year by the name of Mitt Romney.

The question isn’t why so many here eagerly embrace the peripatetic former presidential hopeful, who grew up in Michigan and made his public life in Massachusetts. He’s the closest thing possible to a native son who wasn’t actually born on Utah soil.

The greater mystery is how Romney, given his evident disdain, would get on with President Trump: as another in the lockstep Republican ranks or, some hope, a leader of resistance from within the GOP?

There is ample support for either tack; voters in few, if any, states view Trump with the deep ambivalence felt in Utah.

“There’s a very strong tribal pull to the Republican Party that has many loyal to the president,” said Jim Bennett, whose father and grandfather — both members of the GOP — represented Utah in the Senate for a combined 42 years. Bennett quit the party when Trump became its White House nominee.

Anticipating a Romney candidacy, Bennett suggested that “there is a large contingent of the electorate that wants him to go back to Washington and be that thorn in the side of the Trump administration.”

“The fact [that Trump’s] capable of starting a nuclear war on Twitter,” Bennett said, “far outweighs anything positive he might achieve.”

But Jeff Hartley, a longtime GOP strategist, said many Utah voters are quite pleased with Trump’s policies, high among them the recently enacted tax cut, even if they sometimes find his personal behavior repugnant.

“I don’t think they want to see Mitt Romney go back there and be the strident leader of any opposition,” Hartley said. “They’ll want him to disagree on some issues but agree on a lot of other issues.”

I don’t think [Utah voters] want to see Mitt Romney go back there and be the strident leader of any opposition.

— GOP strategist Jeff Hartley

Romney, 70, a former Massachusetts governor who keeps two homes in Utah, has yet to publicly announce his intentions. Most, though, consider it a foregone conclusion he will seek the Senate seat held by the retiring Republican Orrin G. Hatch. And should he run, it seems a virtual certainty he will win.

“He understands the Washington political arena,” said Jack Sturgeon, 60, a military recruiting officer and enthusiastic Romney backer in Lehi, a fast-growing bedroom community and tech hub about half an hour south of downtown Salt Lake City. “Hatch has a great reputation, but it took years for him to build up. Romney already has the contacts and the reputation.”

Utah Republicans outnumber Democrats by more than 4 to 1, and Romney, who attended Brigham Young University in Provo, gained lasting hero status by helping rescue the scandal-tarnished 2002 Salt Lake Winter Olympics.

Romney also was the first Mormon to win a major party presidential nomination, and his 2012 campaign remains a singular point of pride in a state dominated, culturally and politically, by the church.

“He’s the one guy that could get away with moving into the state and becoming immediately a long-term citizen,” Hartley said.

Utah has been far less enamored of the president, whose boorishness, antagonistic approach to immigration and strident anti-Muslim rhetoric loudly clash with the church’s values of modesty, outreach and religious tolerance.

Trump won Utah with barely 45% of the vote, the poorest showing in any state he carried, and a recent survey showed 53% of residents viewed his presidential performance negatively. Nearly 4 in 10 strongly disapproved.

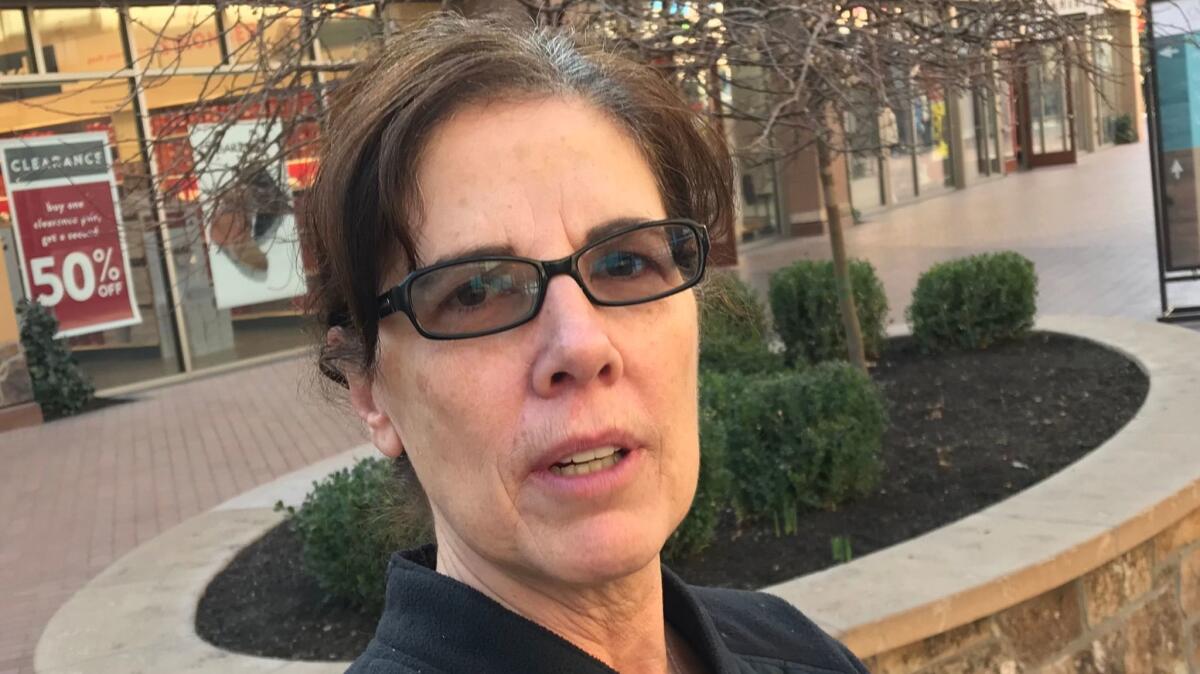

Patricia Hall is among those who can’t abide Trump. She voted for independent presidential candidate Evan McMullin and hopes Utah’s next senator won’t defer to the president out of party loyalty, the way Hatch, who has voted in line with Trump more than 95% of the time, seems to do.

“That’s why I’m glad he quit,” said Hall, 60, who ventured out on a cold, dismal day — a pall of brown haze hung over the Salt Lake Valley like a dirty blanket — to return Christmas gifts at an outlet mall in Lehi.

Marty Przybyla couldn’t disagree more.

There are things — his tweeting mainly — she doesn’t like about Trump. But the 70-year-old retired state worker said she voted for him precisely because he wasn’t a standard-issue politician, and she finds Romney’s criticisms unhelpful.

“He’s too much of an establishment Republican,” Przybyla said of the former Massachusetts governor. “He needs to support the president.”

Romney’s relationship with Trump has been a tortured mix of insult, antagonism and accommodation, starting when Romney, playing elder party statesman, sought to thwart his nomination.

“Donald Trump is a phony, a fraud,” Romney said in a March 2016 summons-to-the-barricade speech at the University of Utah. “His promises are as worthless as a degree from Trump University.”

Trump responded — via Twitter, naturally — that Romney “had no guts and choked” in 2012. “A total joke, and everyone knows it!”

Still, Trump was said to be considering Romney to be secretary of State, or at least appeared to, discussing the job over dinner at one of his Manhattan hotels. Afterward, Romney effused over the president-elect — “I can tell you I’ve been impressed by what I’ve seen.”

Trump, however, ended up choosing Rex Tillerson, and the exercise seemed intended more to humble Romney than serve as serious tryout.

Romney renewed his public criticism of the president after his equivocal response to the racist and anti-Semitic violence last summer in Charlottesville, Va., and, more recently, after he endorsed accused sexual predator Roy Moore in Alabama’s Senate race.

Trump responded by publicly urging Hatch, 83, to seek an eighth Senate term. “We hope you will continue to serve your state and your country in the Senate for a very long time to come,” Trump said, in remarks widely seen as an attempt to block Romney’s candidacy.

After the courtship failed — Hatch announced his intention to step aside earlier this month — Trump and Romney had a cordial phone conversation and, according to the Salt Lake Tribune, the president encouraged him to run.

One intimate said Romney has learned not to take Trump’s disparagement personally. “If he says something evil about you, as long as you don’t overreact, he’ll forget,” said the longtime associate, who asked not to be identified to avoid riling either Trump or Romney.

Another person close to Romney said, if elected senator, “he’s not going to be the voice of ‘never Trump.’”

“The more productive path I think he sees is, ‘Where can I try to influence the president?’” said the Romney advisor, who also requested anonymity because he did not want to speak out before the former governor announced his candidacy. “And in cases where that doesn’t work, he’s going to express his opposition.”

Romney himself has kept mum about his plans. But he dropped what seemed like a big hint: Hours after Hatch’s announcement, he changed the location of his Twitter biography from Massachusetts to Holladay, Utah, a Salt Lake suburb in the shadow of the Wasatch Mountains.

Times staff writer Noah Bierman in Washington contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.