Bay Area leads charge on fixing housing crisis. Will it work for the rest of California?

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — California lawmakers have unveiled a far-reaching package to stem the state’s housing affordability crisis, including new protections against surging rents and evictions as well as more apartments near public transit and in coastal communities.

The proposals could reshape the state’s housing landscape — and they all come from Bay Area politicians.

The chairmen of the Legislature’s two housing committees, Democrats Sen. Scott Wiener and Assemblyman David Chiu, are both from San Francisco. They have a powerful ally in Gov. Gavin Newsom, the former mayor of the city, who has made housing one of his top priorities. And a cadre of powerful Bay Area interest groups has united behind the legislation, providing a level of unity unmatched by any other part of the state.

It makes sense that the Bay Area would take the lead in crafting affordability solutions, since it is saddled with the nation’s highest housing costs. But the Bay Area has distinct characteristics, such as an extensive transit system, that could complicate any universal solution to housing problems. Elected leaders and activist groups from outside the Bay Area fear the region’s lawmakers will push legislation that doesn’t account for the challenges faced elsewhere.

Those fears stem from recent history.

At Gov. Newsom’s urging, California will sue Huntington Beach over blocked homebuilding »

Last year, many Los Angeles activists felt blindsided by legislation written by Wiener to increase housing construction near transit. They worried that it would have undermined recently enacted plans aimed at preventing gentrification and displacement in their communities, and their opposition helped sink the bill.

While lawmakers from outside the Bay Area have been part of the Legislature’s housing debates, some acknowledge they must be more forceful in protecting their constituents’ interests.

“There is a need for us in Southern California to be more aggressive about developing the housing that is absolutely needed and that reflects the needs of our constituencies,” said Assemblyman Miguel Santiago, a Democrat who represents neighborhoods in downtown Los Angeles. “We have got to push really hard on any dollars that are expended in the state of California to match the communities that we represent.”

By housing costs alone, the Bay Area’s affordability problems stand apart from the rest of the state.

Median home values are the highest in the country — with those in Silicon Valley topping $1.2 million and San Francisco’s close behind, according to real estate website Zillow.

Monthly rental costs are also significantly higher than in Southern California, with Silicon Valley rents averaging $2,213 a month in 2017 compared to $1,476 in Los Angeles, per U.S. census data. And while there’s been strong job growth across much of the state since the recession, the Bay Area has seen new employment surpass new homebuilding at a rate unmatched elsewhere, exacerbating a shortage of homes in the region.

“Even as we in Southern California are experiencing strong gentrification and displacement pressures, they’re nothing compared to what has happened in Northern California,” said Manuel Pastor, a sociology professor at USC. “Large swaths of Northern California are out of reach to the average renter and home buyer.”

Wiener and fellow Bay Area lawmakers are setting the state’s agenda on housing policy — a push aided by interest groups from the region.

Over the last 18 months, officials from Bay Area cities, nonprofits, developers, labor groups and others wrote a plan to address the region’s affordability crisis. The idea, called the CASA Compact, relies on numerous changes to state law. In response, Bay Area legislators have introduced bills including proposals that would provide tenants with legal counsel and prevent them from being evicted without cause, and allow homeowners to more easily build second housing units, or casitas, on their properties.

Nearly all the proposals would affect the entire state, which could require other perspectives to weigh in.

Los Angeles and San Diego legislators still retain substantial sway over housing policy. The leaders of the Senate and Assembly are from Southern California, as are those in charge of key budget and fiscal committees. Lawmakers from Los Angeles have put forward legislation on rent control and to end restrictions on public housing, among other plans.

Senate President Pro Tem Toni Atkins (D-San Diego) worked in low-income housing consulting before joining the Legislature and has written major legislation to help fund new projects. At the end of 2018, she put her stamp of approval on Wiener’s aggressive approach to tackling housing problems by creating a new Senate housing committee and naming him the chairman.

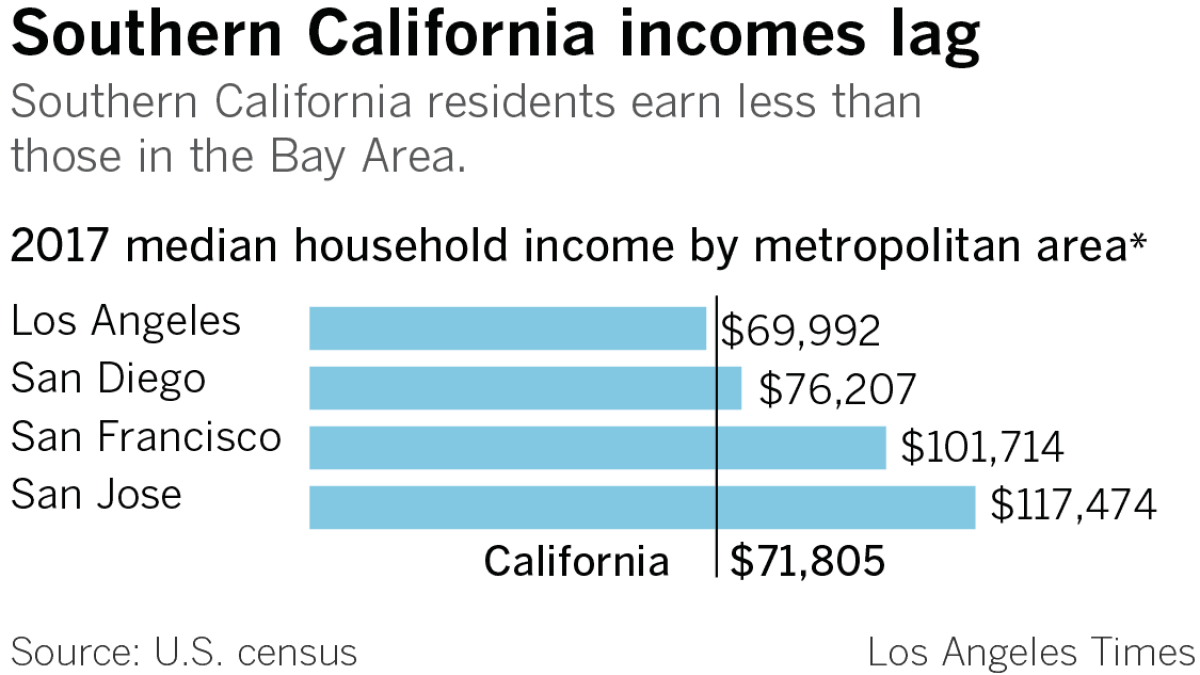

While high housing costs are one reason it’s difficult to afford living in the state, low wages are another. The median household income in the Los Angeles region is below $70,000, which is lower than the state average and just 60% of Silicon Valley’s.

In the Bay Area, “the fundamental problem is different than in Southern California,” said Richard Green, director of the USC Lusk Center for Real Estate. “In Southern California, it’s as much of an income problem as it is a housing problem.”

The socioeconomic divide between the areas was underscored last year when Wiener introduced the bill that would have made it easier to build apartments near transit stops.

Activists in Los Angeles had just finished a decade of work on a development blueprint for historically black and Latino South Los Angeles and a plan to boost density near transit lines. Concerned that Wiener’s bill would override their efforts and displace longtime residents, they opposed it, helping torpedo the bill in its first committee hearing.

Mariana Huerta Jones, campaign and communications manager for Alliance for Community Transit-Los Angeles, said Wiener took the group’s criticisms to heart and incorporated many of its ideas — including stricter prohibitions against demolishing rental housing — into Senate Bill 50, a new version of the legislation he’s introduced this year. The measure would allow for four- or five-story apartment complexes and condominiums near transit.

Her organization has yet to take a position on the bill but is speaking regularly with Wiener’s office about further changes, Huerta Jones said.

“The senator really is genuine and wants to do something about the housing crisis,” she said. “We really appreciate that, and it’s exciting he’s being bold. But being bold also means being humble and appreciating how what you’re proposing could have impacts across the state — all the way down to San Diego and into rural areas.”

This year’s version of Wiener’s bill, as well as others in the suite of Bay Area housing legislation, could disrupt some policies that have strong backing outside the region.

In the 1970s, San Diego voters implemented a 30-foot height limit for construction along the city’s coastline and required a public vote to build taller. Wiener intends for his bill to override that rule for housing near transit. Sen. Nancy Skinner (D-Berkeley) has introduced Senate Bill 330 to do away with many city and county restrictions on homebuilding for a decade — a response, she’s said, to the scope of the state’s housing challenges. San Diego’s coastal height limit would be suspended for new homes should the bill pass, a spokesman for Skinner said.

While still early in the legislative process, Skinner’s bill also could affect how much the city of Los Angeles could charge developers through a fee passed in late 2017 that aims to raise millions to build low-income housing and is a key plank in Mayor Eric Garcetti’s housing agenda.

Wiener said it is vital for Bay Area lawmakers to understand other areas of California and pointed to his efforts to incorporate feedback from Los Angeles activists into SB 50. But he said many housing concerns are the same throughout the state, noting he often receives the same pushback to his ideas that propose changes to neighborhoods in San Francisco and Los Angeles alike.

“It’s not so different when it comes to education policy that affects the whole state,” Wiener said.

Chiu, the housing committee chairman in the Assembly, said it’s possible Bay Area legislators could scale back their housing bills so that they only affect that region. But sometimes, he said, housing problems are best tackled by those on the outside.

Last year, Chiu wrote legislation to withhold state housing dollars from any community that allowed its City Council members to block homeless housing developments in their districts before a formal vote. Chiu introduced the bill to stop the practice in the city of Los Angeles, where council members had recently stymied projects in their districts by holding back support before a council hearing.

Chiu said activists in Los Angeles asked him to carry the bill because it was too politically fraught for a legislator from Southern California to do so. Both houses of the Legislature approved the measure unanimously, and then-Gov. Jerry Brown signed it into law.

“There were many significant leaders in Los Angeles that were happy to see it pass,” Chiu said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.