Iowa gets ready to answer Democrats’ big questions

- Share via

DES MOINES — Democratic hopefuls raced Sunday from one Iowa campaign stop to the next, rallying supporters and making their final pleas to the still-undecided in a climactic finish to a presidential contest with no commanding front-runner and no obvious outcome.

With the Super Bowl curtailing the usual election-eve appearances, candidates saturated the airwaves and social media and staged football-themed parties to squeeze in whatever politicking they could between plays.

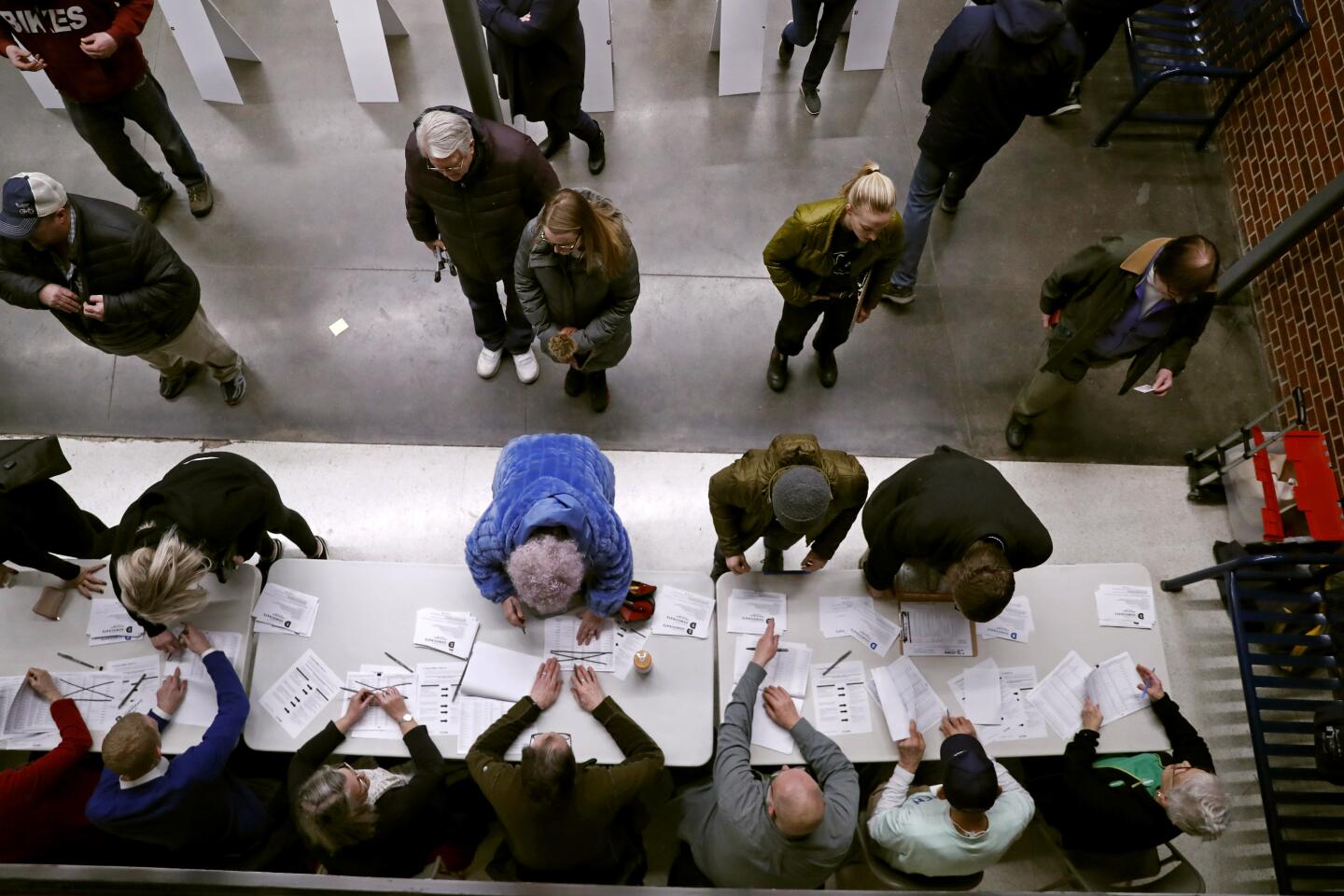

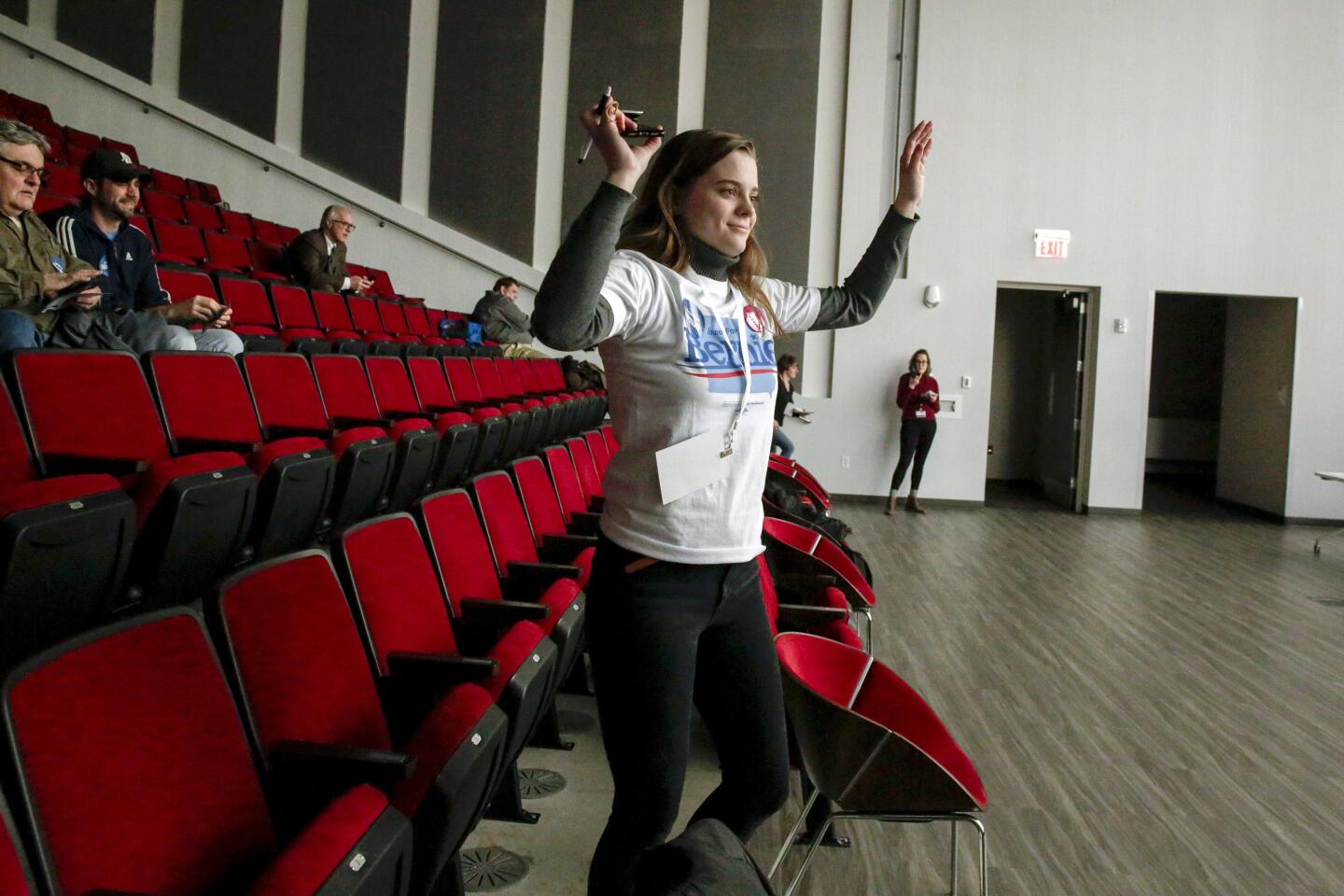

The caucuses, a series of more than 1,600 community gatherings, begin at 7 p.m. Central time Monday and their outcome will go a considerable way toward shaping the steeplechase of contests that follow, starting with next week’s New Hampshire primary. Iowa will effectively eliminate several candidates and boost others.

More broadly, the balloting represents the first electoral test of strength between the party’s ideological wings and across its generational divide, the pivot points around which the contest has turned for roughly the last year.

It will also test whether voters reward consistency, the near-metronomic repetition of Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders, or prefer candidates, like Elizabeth Warren and Pete Buttigieg, who have been testing different messages and strategies as the campaign has worn on.

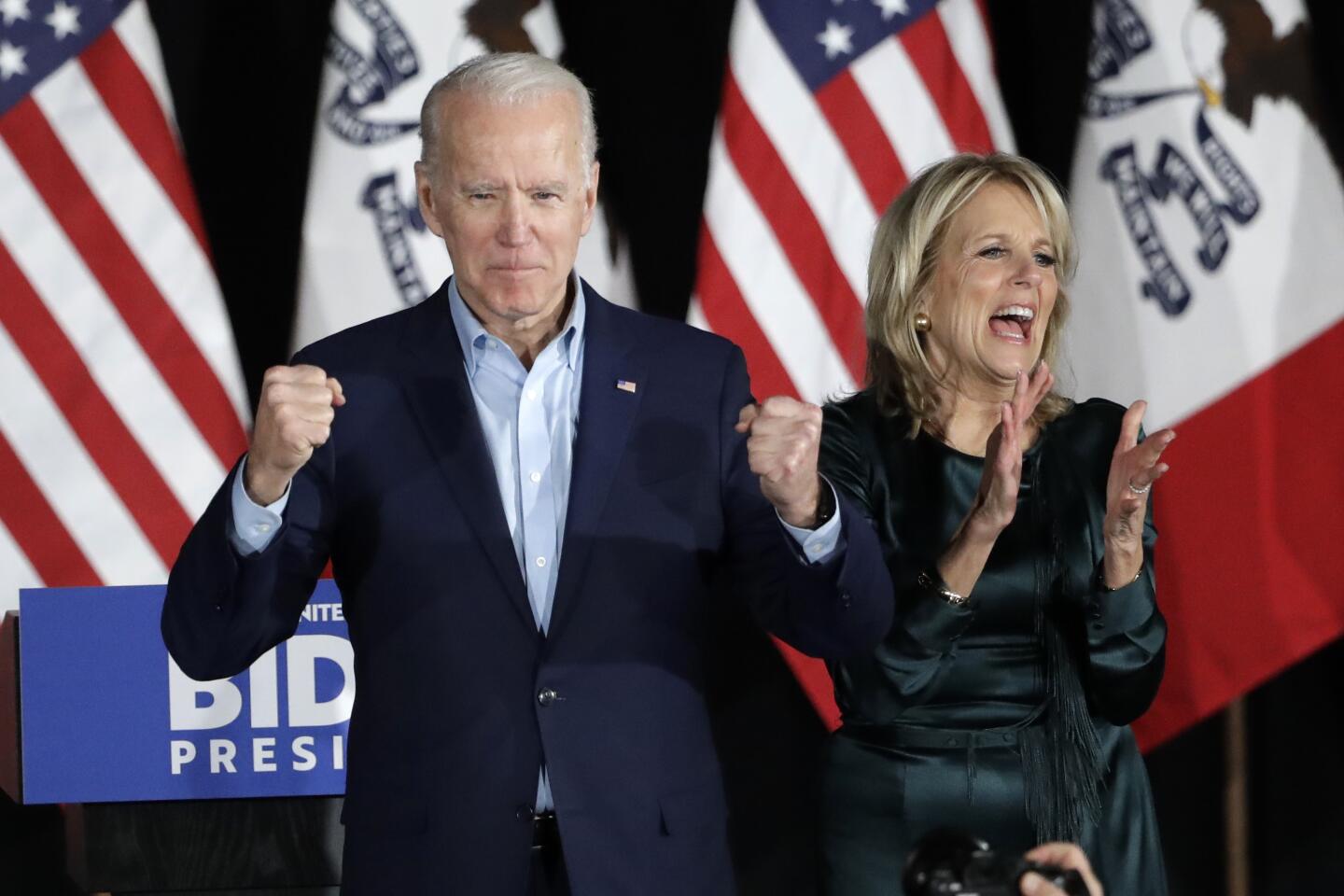

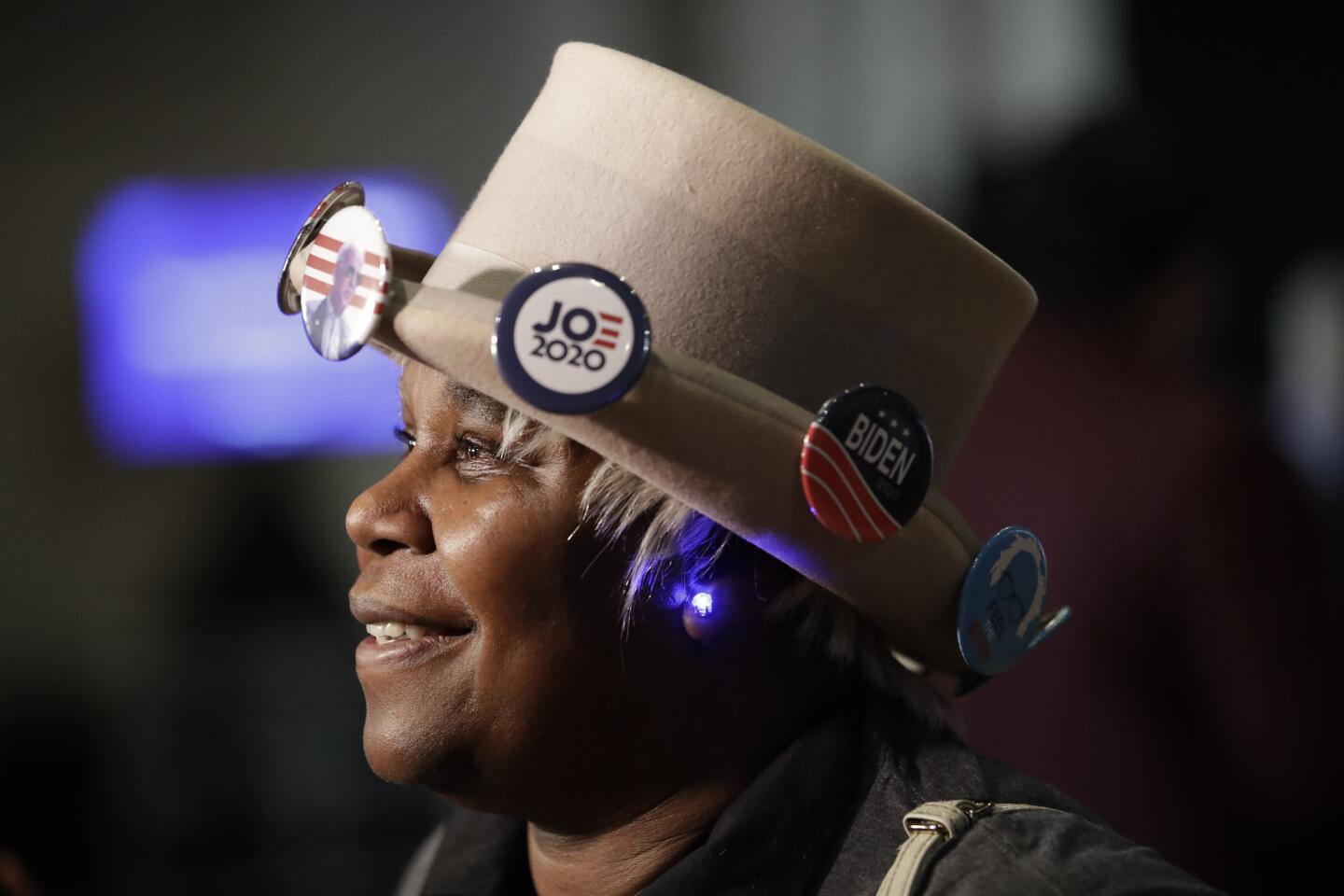

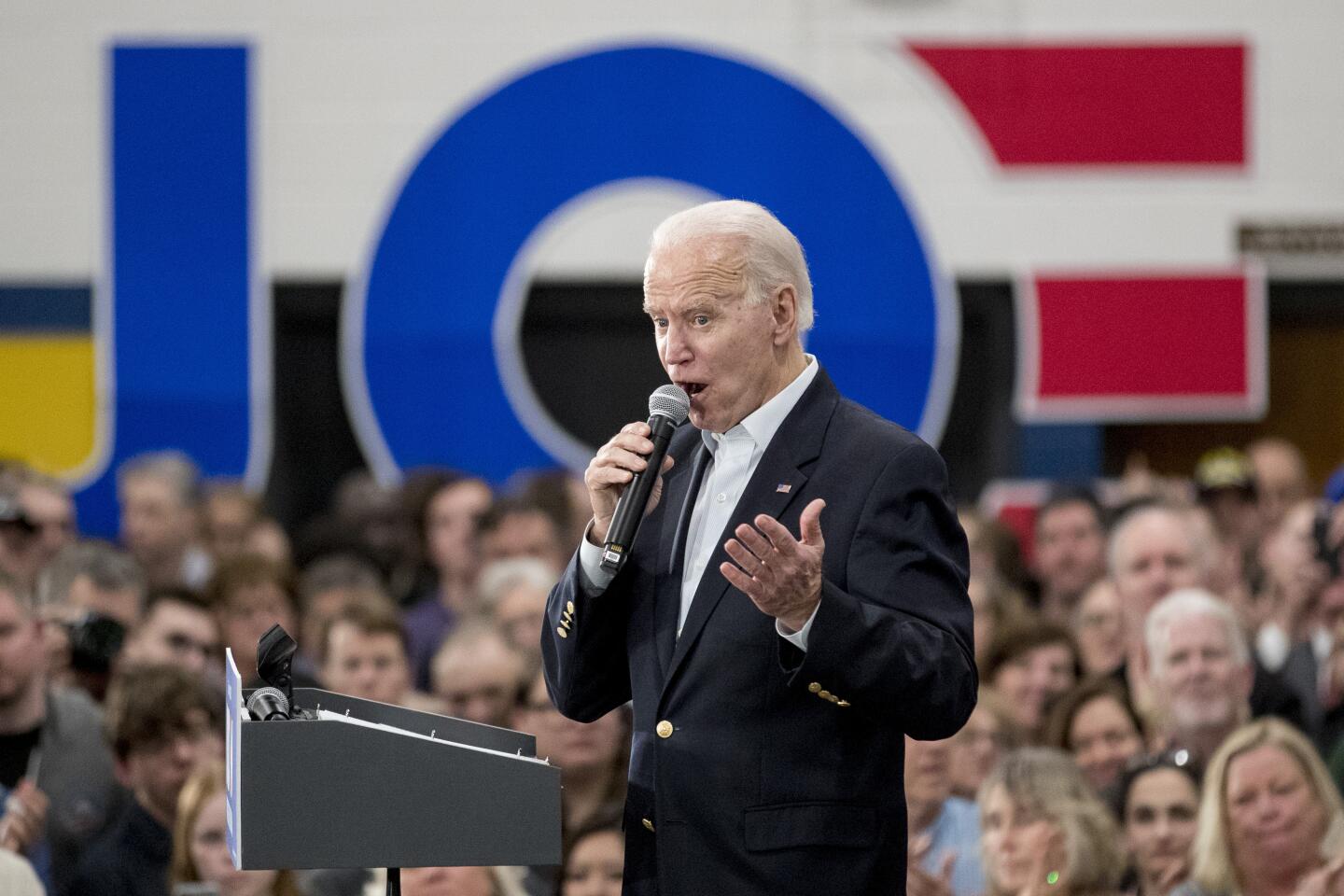

The two leaders in national surveys, former Vice President Biden and Vermont Sen. Sanders, finished their Iowa campaigns where they started, with arguments almost unchanged from the day they began seeking the White House — Sanders for the second time and Biden for his third.

“We’ve got to pull this country together. We’ve got to heal it,” Biden told audiences, focusing — as he has consistently — on the Republican incumbent and largely ignoring his Democratic rivals. “Look what Donald Trump stands for, how he behaves. My response is always the same: America is so much better than this.”

Sanders, who waged a far-stronger-than-expected White House bid in 2016, has hit the exact same notes as then: An economy that works for everyone and “not just the billionaires.” A more pro-labor agenda. “Medicare for all.” And, since President Trump was elected, a new mission, getting a “dangerous and dishonest” president out of office.

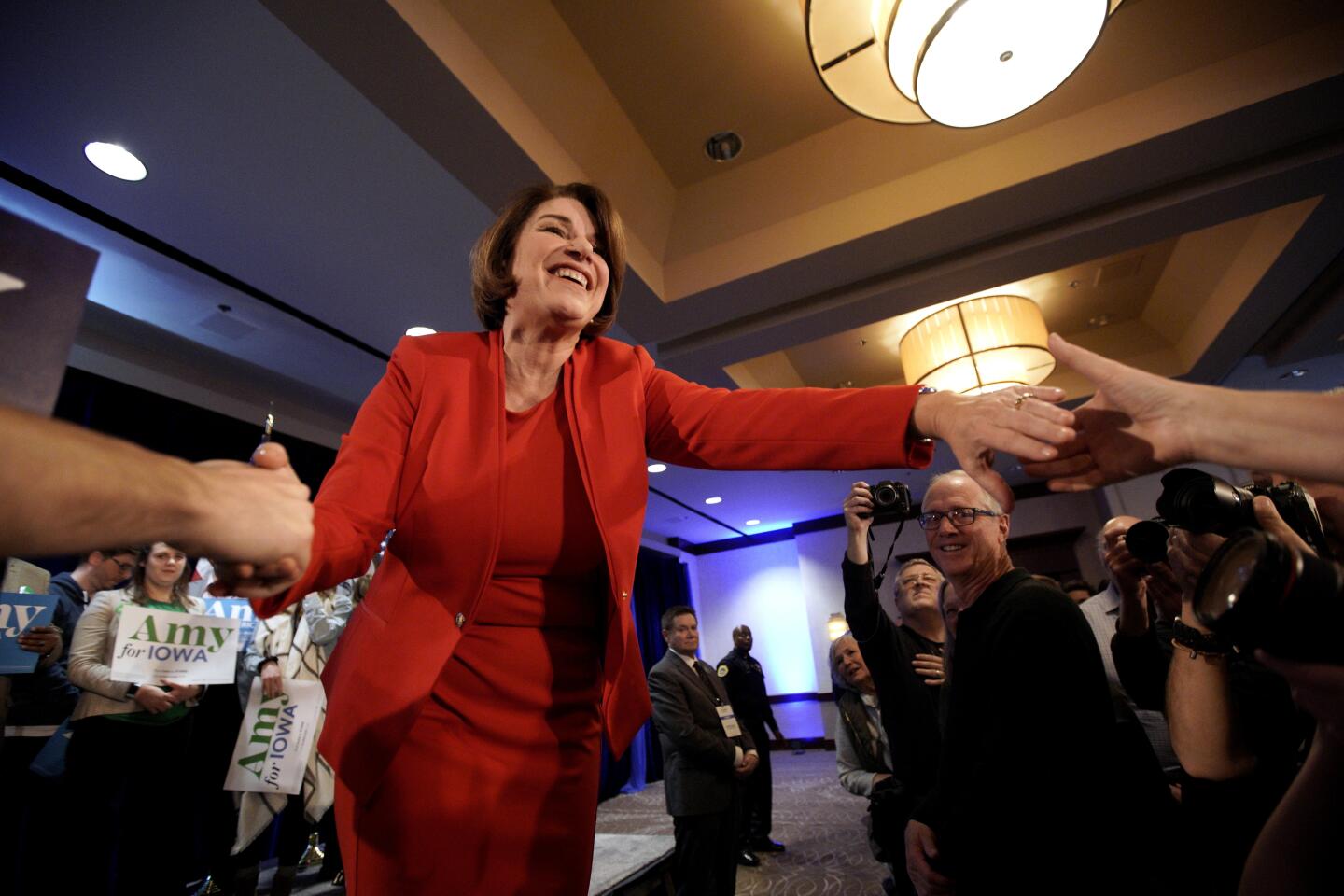

Their two leading Iowa rivals, Massachusetts Sen. Warren and former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Buttigieg, approached the caucus finish line sounding themes that reflect notable course changes.

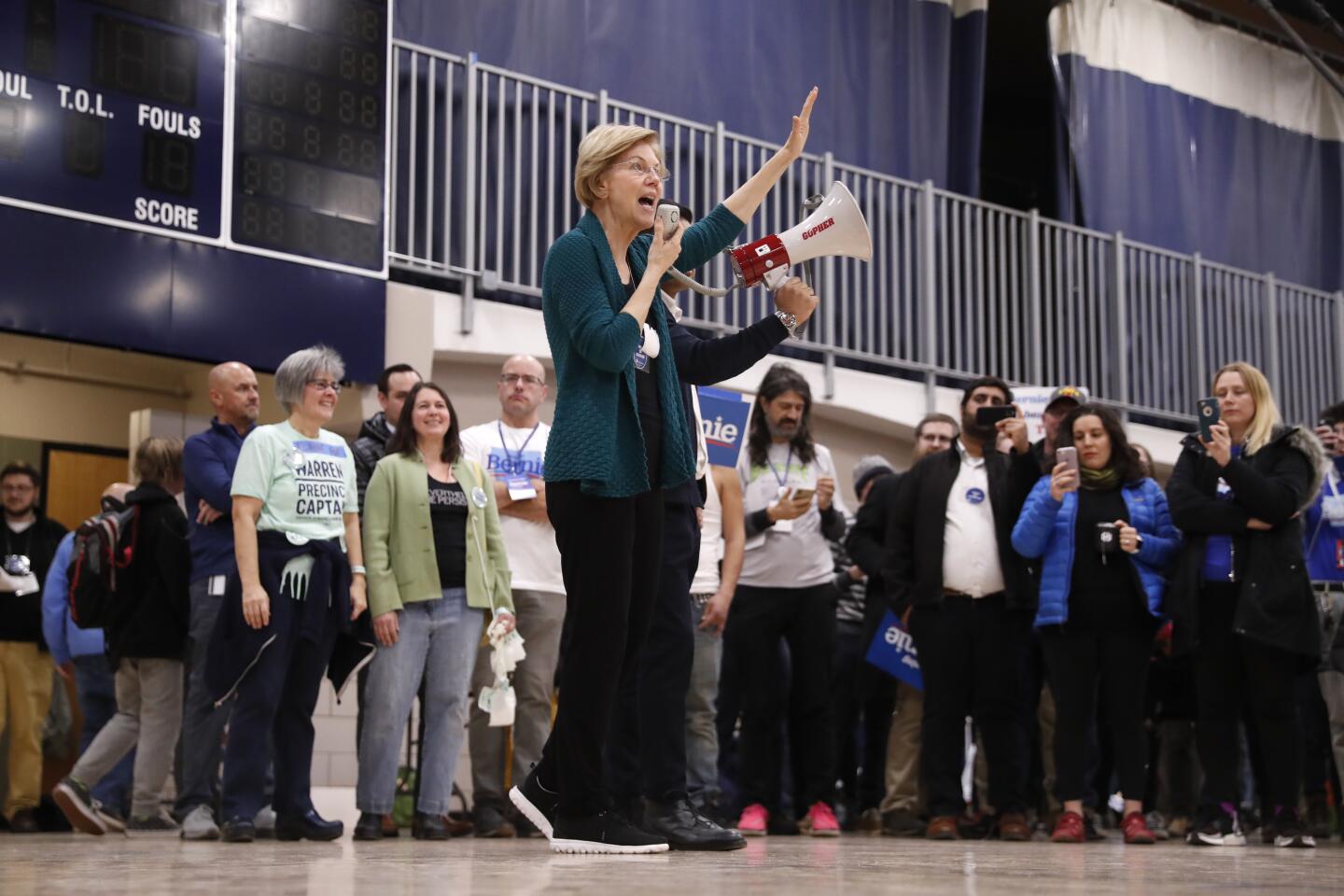

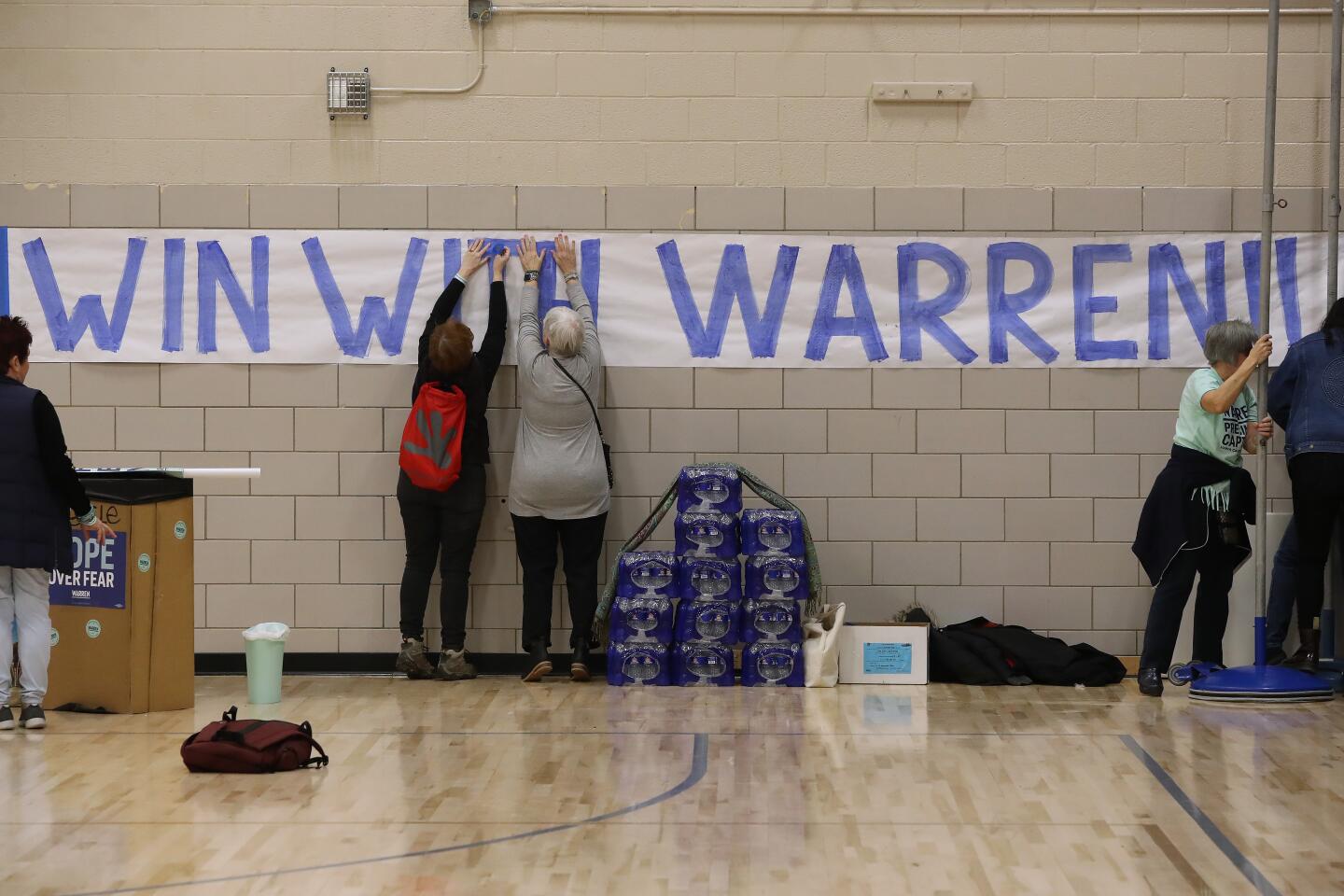

Warren, who started the campaign talking little about Trump and much about her thick sheaf of policy proposals, said she could not only oust the president but unite a party now divided among supporters of more than half a dozen candidates.

“We might have had some different ideas. We may have had some different ways to go about it,” Warren told supporters in a packed college hall in Indianola. “But in the end, we all have one goal, and we better come together to meet that goal. We are going to beat Donald Trump.”

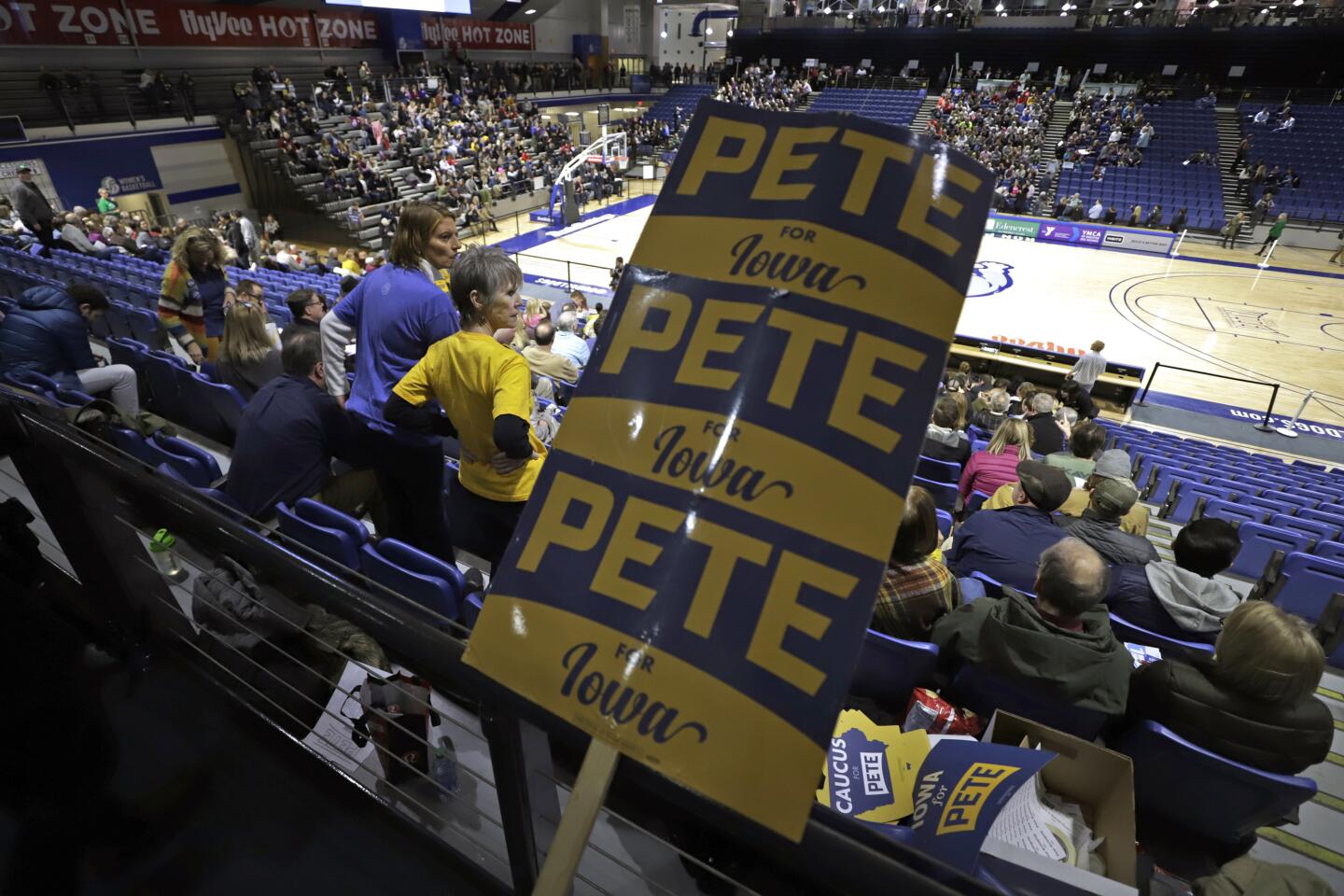

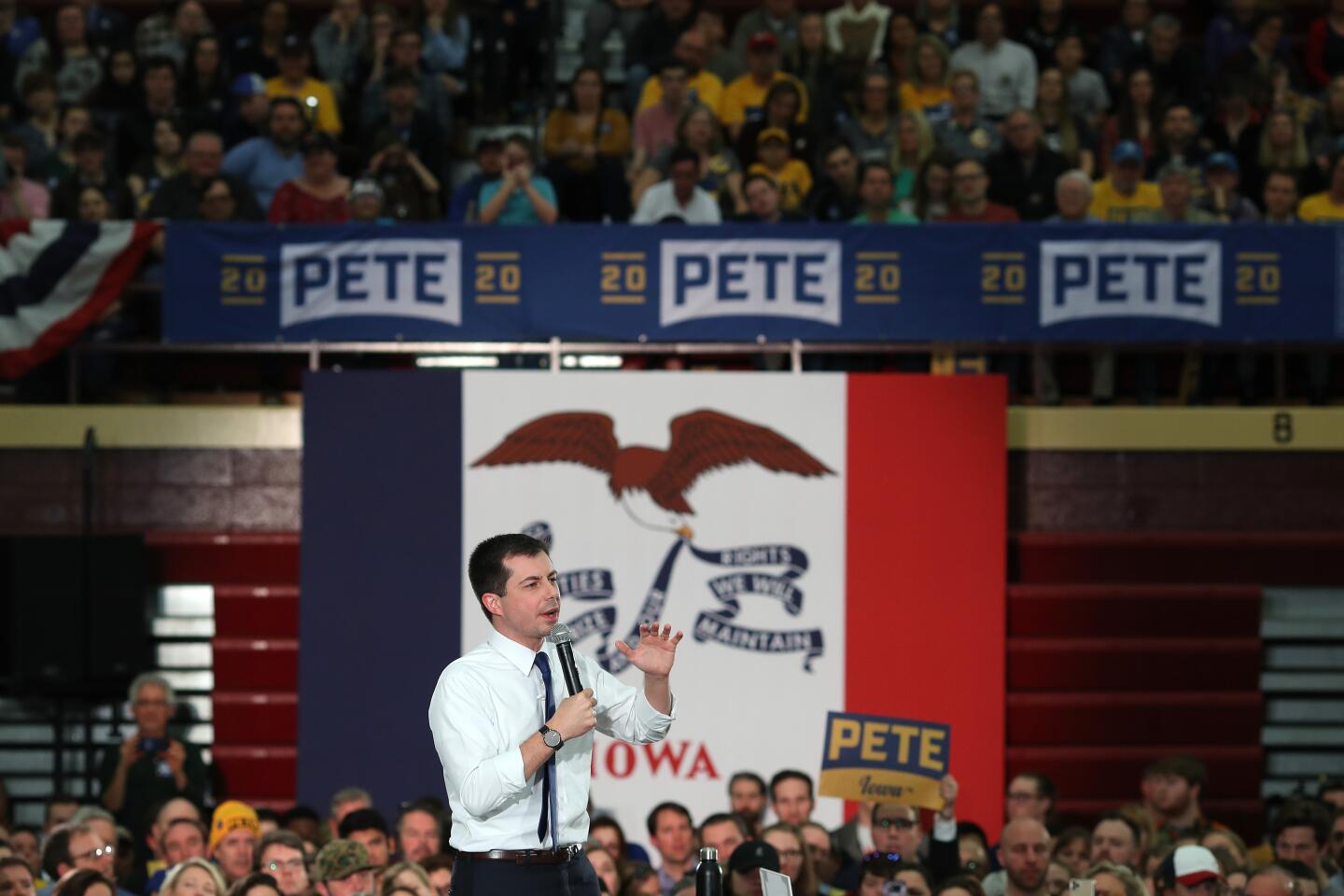

Buttigieg, who started out running with appeals to the progressive wing of the party, closed with a more moderate-sounding message, taking aim at Sanders and the lingering left-versus-center resentments of the last nominating fight.

“Let’s agree that the less 2020 reminds us of 2016 the better,” he told the crowd at a high school in Coralville. “We’re going to have a different kind of election.”

Dubuque’s experience shows issues at play in the 2020 Democratic presidential campaign — race, justice, a reckoning with America’s history of enslaving blacks — are universal ones.

The unvaried messages of Sanders and Biden have contributed greatly to their ability to maintain a relatively stable base of support despite, in Sanders’ case, a heart attack and, in Biden’s, several rocky debate performances.

The former vice president and six-term Delaware senator, who sought the White House the first time in 1988, launched his campaign arguing he is best equipped to beat Trump and defend the policies of Barack Obama, the president he served for eight years. Portentously, Biden cast the 2020 contest as a “battle for the soul of the nation,” a phrase now emblazoned on his campaign bus.

“This is no time to take a risk,” says the narrator in one of Biden’s final Iowa TV spots. “We need our strongest candidate. So let’s nominate the Democrat Trump fears the most. Vote Biden. Beat Trump.”

For Sanders, his unwavering decades-long advocacy of universal, government-managed healthcare and other progressive goals is a major attraction for his dedicated followers, who thrill to familiar lines like concertgoers cheering a performer’s greatest hits.

“He’s been saying the same thing for 30-plus years, and I think that’s very important,” said China Johnson, a 21-year-old from Indianola. “I enjoy Elizabeth Warren, but she used to be a Republican, and that kind of bothers me.”

Sanders’ campaign has dramatized his unchanging emphasis in a TV ad stringing together years of archival footage. “I’ve spent my entire political life fighting for those people who do not have the wealth and the power,” he says in a clip from 1990, the first in a montage spanning more than a quarter of a century.

At a time when some voters have wearied of the erratic, unpredictable Trump presidency, constancy may be a particularly appealing virtue in 2020.

“They’ve both benefited from consistency, steadiness,” Bill Carrick, a Democratic strategist with decades of presidential campaign experience, said of Sanders and Biden.

“They’re not creating controversies about their positions,” said Carrick, who is neutral in the party’s nominating contest. “It’s helped them communicate more efficiently and effectively.”

But Warren and Buttigieg are tapping another impulse among Democrats: a desire for generational change and diversity that is not easily satisfied by a pair of septuagenarian white men. (Sanders is 78, Biden 77.) That has helped fuel the campaigns of Warren, 70, and Buttigieg, a gay man who turned 38 last month.

Sometimes conflicting urges, the desire for stability and the longing for change, can be found in a single voter.

Linda White sported a big “precinct team member” button as she waited for a group photo with Buttigieg after a rally in Marshalltown. “I love Pete because he is young and fresh,” she said. “He doesn’t have that D.C. baggage.”

But when asked her second choice should Buttigieg fail to meet the 15% “viability” threshold at her caucus, White sounded almost sheepish. “I’d have to go Biden,” she said. “Biden is very knowledgeable.”

Early on, Buttigieg won praise from progressives with such dramatic proposals as abolishing the electoral college and restructuring the Supreme Court. He supported Medicare for all. But those reform ideas are no longer so prominent in his stump speech, and he instead advocates “Medicare for all who want it,” which, polls show, is more appealing to a broad chunk of the electorate.

He started his campaign calling for an end to political division. Now, he increasingly takes shots at his rivals by name.

“Vice President Biden is making the case that this is no time to take a risk on someone new,” he said in Ankeny. “I would argue this is no time to take the risk of falling back on the familiar or relying on an old playbook that helped get us to this point.”

He slammed Sanders for sending a message that “you’re either for revolution or you’re for the status quo.”

Warren has spent her political career focusing on an anti-corruption message and a call to transform a government dominated by special interests and the wealthy. That through-line and a slew of detailed policy proposals fueled her steady rise last year to the top tier of candidates.

But in October she fumbled the rollout of her healthcare plan, first offering a fulsome Medicare-for-all proposal, which came under fire as being costly and impractical, then quickly retreating to a more incremental approach. It took a toll and damaged her wonkish credibility.

“One thing that drove her when she was hot was her authenticity; she had a very clear theory of the case, very sharp message and concrete plans,” said Doug Thornell, who was a senior aide to Howard Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign. “That authenticity was damaged when she shifted her messaging and the plan became muddled.”

One of the supporters it cost her was Dan Fessler, a 33-year-old Wells Fargo employee in West Des Moines. He had planned to caucus for the Massachusetts senator, but recently flipped to Sanders after kidney failure saddled him with $8,000 in medical bills. “Medicare for all sounded more and more appealing,” Fessler said.

This being Iowa, where caucusgoers pride themselves on thinking for themselves, he lives in a house divided.

His wife, Shauna, 32, is still leaning toward Warren. “I would feel maybe like a traitor,” she said, “not supporting the female candidate.”

Times staff writers Tyrone Beason in Coralville, Seema Mehta in Indianola, Melanie Mason in Des Moines and Matt Pearce in Iowa City contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.