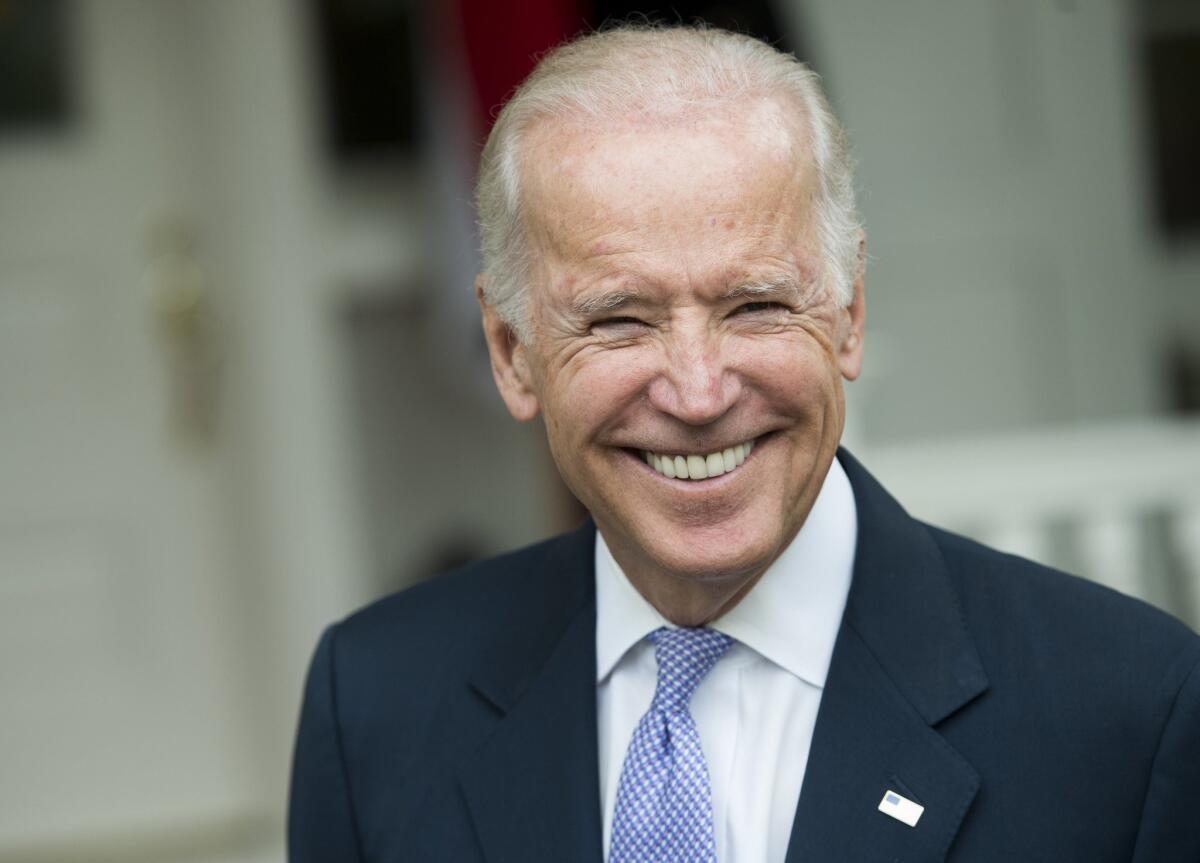

After big night for Biden, the fight ahead will test whether he or Sanders can expand their coalitions

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The drive to political revolution has hit a big speed bump.

In the first coast-to-coast, multi-state primary of the 2020 campaign, former Vice President Joe Biden swept across the South and battled Sen. Bernie Sanders to a draw in key northern states because of overwhelming support from African Americans and a surge from voters who decided just in the last few days whom to support.

The result dashed Sanders’ hope of becoming the prohibitive front-runner as a result of the Super Tuesday voting — an ambition that seemed within his grasp until Biden resurrected his campaign on Saturday in South Carolina.

The Vermont senator was slowed, but not stopped, by a newly energized party establishment that has rallied behind Biden in the last four days. As a result, the Democratic Party that just days ago wondered whether Sanders would emerge from Super Tuesday with an insurmountable delegate lead is now girding for a protracted two-man fight. It will pit an establishment-backed, old-school Democrat against an independent progressive who wants to upend the party.

The results dealt a potentially fatal blow to the campaign of former New York Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg, who will be under pressure to abandon his campaign after spending more than $660 million to garner just a handful of delegates. In North Carolina, for example, the billionaire candidate invested heavily. Biden crushed him, cruising to an easy victory and relegating Bloomberg to a distant third.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts lost her home state to Biden. Although she has vowed to continue her campaign, her future seems limited.

The primaries over the remainder of this month — especially in big, delegate-rich states including Michigan, which votes next week, and Ohio, Illinois, Georgia and Florida — will test the ability of both the leading candidates to reach beyond their comfort zones.

So far, each has drawn strength from different swaths of the electorate.

Biden’s coalition of blacks, older voters and suburban moderates helped him trounce Sanders across the South.

Sanders’ coalition of young people, Latinos and urban voters boosted him in the West. He won Colorado and Utah and is projected to win California, where the vote count will continue late into the month as officials sort through millions of late-arriving mail-in and provisional ballots.

Texas, where the two candidates’ coalitions are both well represented, proved to be a close battleground: The two seemed poised to split the prize in that state, which has the second-largest delegation to the party’s nominating convention.

Biden’s performance on Super Tuesday was a remarkable demonstration of how his breakthrough in South Carolina and the endorsements that followed could compensate for glaring weaknesses that had contributed to poor showings in the first three states to vote.

He had a thinly staffed organization throughout Super Tuesday states, anemic fundraising and little advertising, leading many analysts to question whether he would have the resources to capitalize on his South Carolina win.

In the event, none of that mattered. Even without traditional campaign infrastructure, Biden’s abrupt change of fortune after South Carolina had a big impact on a Democratic primary electorate that included many late deciders — voters who opposed Sanders’ policies or doubted he could beat President Trump, but who had a hard time deciding on the best alternative.

In Virginia, for example, preliminary exit polls found that about half of voters chose their candidate in the last few days — a share that was considerably larger than typical. Half of these voters chose Biden.

Similarly, in Massachusetts, half of the voters decided in the last few days. Among them, Biden was supported by more than 4 in 10 — more than any other candidate, according to the exit poll done for the major television networks by Edison Research.

One of the day’s late deciders was Yolanda Lampkin, a 62-year-old travel agent in Alabama who was still trying to pick a candidate when she parked at her polling station.

She’d been considering voting for Warren or Sanders, she said, but had just heard a radio ad in which Alabama Sen. Doug Jones urged support for Biden as the best candidate to beat Trump.

“OK,” she told herself. “I’m going to go with Biden.”

One of the clearest examples of how late-deciding voters could swing an election came in Virginia. The state allows only very limited early voting, so Biden harvested the full impact of his South Carolina victory and the late endorsements of two of the state’s most popular Democrats, Sen. Tim Kaine and former Gov. Terry McAuliffe.

Warren and Bloomberg also made strong plays for well-educated suburban voters in the state, and as recently as last week polls found both of them potentially competitive. But Biden swept Virginia, taking 53% of the vote in nearly complete returns, to 23% for Sanders. Bloomberg and Warren both ended up well below the 15% threshold for winning statewide delegates there.

Biden was helped by voters like Dwight Robinson, a 66-year-old retiree from Herndon. He almost voted for Sanders but worried the Vermont senator wouldn’t be able to beat Trump. Instead, he cast his ballot for Biden, although he told a reporter that Biden needed to “get the fire in his belly” to win the general election.

The Super Tuesday returns put to rest questions about whether Biden’s big win in South Carolina — and his landslide among black voters — was a one-shot triumph thanks to his endorsement by the influential South Carolina party leader, Rep. James E. Clyburn.

Across the South, exit polls found that about two-thirds of African American voters in Super Tuesday states supported Biden, compared with about one-sixth who backed Sanders.

Exit polls also pointed to the ideological division within the party that will define the coming debate between Biden and Sanders: Just over 4 in 10 voters said they wanted the next president to return to the policies of the Obama era — a legacy that is embraced by Biden; just under 4 in 10 wanted more liberal policies, as Sanders has advocated; 1 in 10 wanted more conservative policies.

While Sanders has struggled to gain traction among black voters, Latinos have become an important part of his coalition, which is a big part of why he had been expected to do well in California, Colorado and Texas.

Sanders won Colorado, but three other candidates — Biden, Warren and Bloomberg — were also on track to claim a share of the state’s delegates.

In Texas, Biden drew support from moderates like Antonio Brinkley, 57, an administrator who works with at-risk youth, who doesn’t like big government and opposed Sanders.

“He can bring in moderates” and beat Trump, Brinkley said.

Sanders tapped into young voters like Erek John, a University of Houston student who thinks the progressive senator can drive turnout among young and minority voters.

“He has a way of galvanizing his base the way Trump does that Biden just doesn’t,” said John, 21.

Some analysts argue that Sanders’ strong progressive agenda could create a ceiling on the support he can garner, while Biden may have more room to grow among independent and Republican voters.

But as the exit polls on Super Tuesday showed, both Biden and Sanders have complementary weak spots: Biden excels among older voters, but flags among the young; Sanders has strong support among young voters, not so much among older ones. And both will have work to do to connect with college-educated white women — a swath of voters that may be up for grabs if Warren drops out of the race.

The coming contests will be a test of whether either of them can address their weak spots and reach beyond their bases to close the deal on the nomination — and to unite their party for the coming battle against Trump.

Times staff writers Molly Hennessey-Fiske contributed to this report from Houston , Jenny Jarvie from Birmingham, Ala., and Erin Logan from Herndon, Va.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.