How one man’s coronavirus infection created a web of potential infection around the world

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Contracting the new strain of coronavirus was stressful enough for one 55-year-old Washington, D.C., aerospace consultant. But tracking down and calling the people he came into contact with may have been just as bad.

“Are you sitting down? I got bad news,” he told people at least a dozen times.

The consultant was diagnosed Friday with the illness, one among the early waves of known cases in the United States. And his efforts to call people around the country and around the world — including some within the highest reaches of government — illustrate how far a single individual can potentially spread the virus.

His calls caused factories to shut down, airlines and a ski van service to contact everyone on their manifests, a hotel to draft a letter sent to their guests, and congressional advisors and officials in the Israeli government to consider who they might need to call.

In a phone interview Sunday, he said he was suffering from painful coughing and shortness of breath. His wife has been feverish.

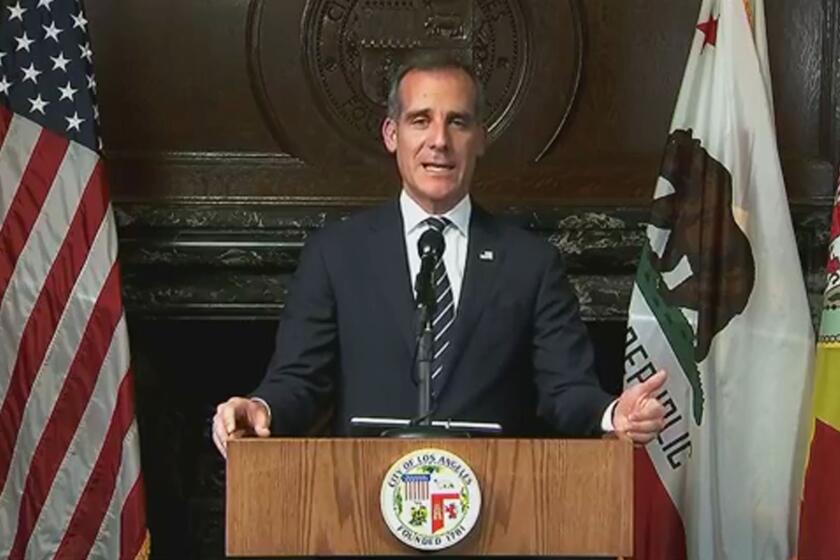

Los Angeles bars must close and restaurants must stop dine-in service in an effort to slow the spread of coronavirus, Mayor Eric Garcetti said Sunday night. Restaurateurs and bar owners fear many establishments might not reopen.

The consultant asked that his name not be used to protect the privacy of his clients. But he agreed to tell his story as a warning for others to listen to government admonitions and follow social distancing guidelines.

His story begins at the American Israel Public Affairs Committee conference in Washington at the beginning of the month.

The consultant met with high-ranking defense officials from Israel and defense industry leaders from the United States. He said he most likely contracted the virus from someone there. Since then, at least half a dozen people who were in attendance at that conference have been diagnosed.

But the consultant did not know he’d been infected. So he continued going to Capitol Hill to hold meetings. He went to a professional hockey game and sat in one of his client’s seats in a booth with two factory employees. He flew to Vail for a five-day ski vacation with his children.

He started feeling a little strange on Tuesday, his last day on the slopes — some coughing and a slight fever. He figured it was the altitude.

He got on the plane that night and started coughing more, drawing uncomfortable stares from fellow passengers.

The latest maps and charts on the spread of COVID-19 in California.

Thursday, he went to the hospital, which was initially reluctant to test him. His temperature was only 99.3 degrees.

But he insisted, explaining he had already had a recent flu and had been to the AIPAC conference, two red flags that prompted medical staff to put him in an isolation room for four hours while they sought permission from the Health Department to test him.

He got the bad news Friday morning and immediately started calling people, at least a dozen. He was anxious and a bit embarrassed.

“I just felt terrible that I was that guy,” he said. “When I told them, there was silence on the other side.”

He was relieved that the Israeli officials had already been required to self-quarantine when they returned home. “Those guys are OK,” he said, “so it’s the other people I’m worried about.”

When he wasn’t coughing, he kept calling — congressional offices, companies, his hotel in Vail, the van service that took him and his kids to the slopes. The airline kept him on hold for hours; his travel agent finally got through.

The hotel sent a letter to their guests. The van service said it had expected a call like his and was prepared to make calls to the 10 people or so from around the country who rode through the mountains with the contagious consultant. The company that gave him the hockey tickets had to shut down their factory to test employees, as did other businesses he interacted with.

Some people he spoke with needed him to write memos with key dates and times that they could show their own doctors.

“As soon as I found out, I started banging away the calls because I did not trust anyone to do the forensic work for me” of contacting and warning those who might have been exposed, he said, “and I was right, no one did call.”

When he reached people, after an initial silence, they were understanding, much to his relief.

“Politics didn’t matter when I spoke with these people,” he said. “We get it. We’re going to try to do the right thing.”

The hospital told him to call ahead if he needed to return, so they could set up an isolation room with respiratory equipment.

“I think a lot of people have it and don’t know it, people who have been turned away,” he said. “The symptoms are flu-like, and you don’t have to be that sick.

“They only tested me because of the fact that I went to a big conference and I pushed the issue with them,” he added.

Like many Americans, he is already weary of the isolation.

“I feel like Jack Nicholson in ‘The Shining.’ I’m about to snap with this cabin fever.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.