Supreme Court rules electoral college representatives must honor choice of state’s voters

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Anxious to avoid chaos in the electoral college just months before the November vote, the Supreme Court ruled Monday that electors who formally select the president can be required by the state they represent to cast their ballot for the candidate who won their state’s popular vote.

The justices unanimously rejected the claim that electors have a right under the Constitution to defy their states and vote for the candidate of their choice.

“Electors are not free agents,” Justice Elena Kagan said for the court in Chiafalo vs. Washington. “They are to vote for the candidate whom the state’s voters have chosen.” Article II of the Constitution and the 12th Amendment “give states broad power over electors, and give electors themselves no rights,” she said.

The electoral college system, created by the Founding Fathers, has been criticized as being outdated and unfair to voters. In two of the past five presidential elections, the winner came in second in the national vote but nonetheless won a combination of states that yielded more electoral votes.

The dispute before the high court could have injected an additional element of uncertainty into the presidential race.

Supreme Court rules for civil rights protection for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer employees.

Last year, the U.S. 10th Circuit Court of Appeals in Denver surprised election officials when it ruled that the Constitution as written in 1787 assumed the state’s electors were free to vote for their favored candidate, and if so, the same is true today.

Constitutional scholars counter that although electors may have had an independent vote at the time of the nation’s founding, they have been required since the early 1800s to vote in line with the wishes of the party whose presidential candidate won the state’s vote.

In 1804, the 12th Amendment made clear that electors would cast separate ballots for president and vice president, which confirmed “the electoral college’s emergence as a mechanism not for deliberation but for party-line voting,” Kagan said.

Ever since, the parties have chosen slates of electors who pledge to cast a ballot for the party’s presidential candidate if he or she wins the state’s vote.

Paul Smith, an election law expert with the Campaign Legal Center, said the decision prevents a potential scramble over wavering electors in November.

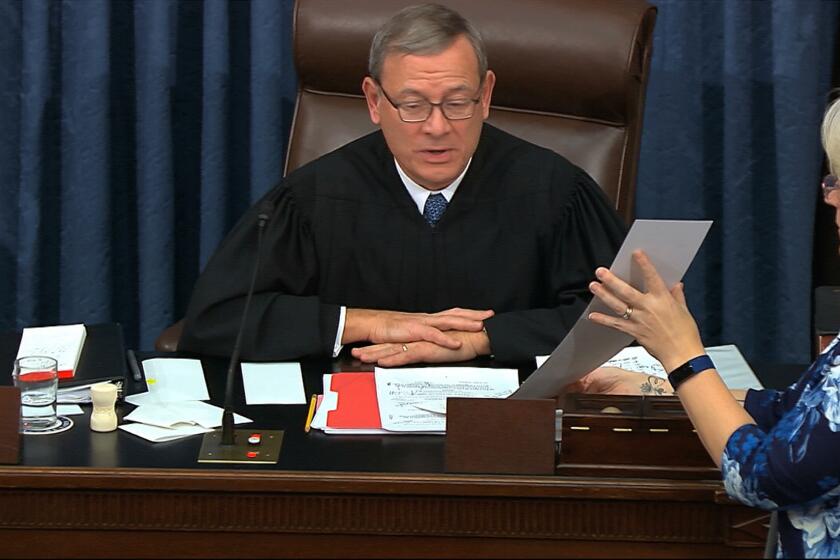

Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. tried to be neutral in presiding as a divided Senate judged Trump, but his refusal to intervene to allow witnesses vexed some.

“Voters should go to the polls with the confidence that their vote will count and that their political system will be free from corruption,” he said. “However far from perfect the current system may be, the chaos of an unbound electoral college would have been even worse.”

In nearly every election, there are a handful of “faithless electors” who ignore their commitment and cast a vote different from their state’s voters. But these stray votes have been ignored and never made any difference in the outcome.

Most states have laws or rules that require the electors to abide by their pledges and to follow the state’s wishes. The Supreme Court agreed to hear two cases on the issue, one from Washington, where the state prevailed, and a second one from Colorado, whose binding rules were overturned.

Monday’s ruling upholds a $1,000 fine against Peter Chiafalo, one of three Washington state electors who cast their ballots for Colin Powell rather than for Democrat Hillary Clinton, who won the state’s popular vote.

Harvard University law professor Lawrence Lessig, who represented the electors, said he was not entirely disappointed to lose.

“When we launched these cases, we did it because regardless of the outcome, it was critical to resolve this question before it created a constitutional crisis. We have achieved that. Obviously, we don’t believe the court has interpreted the Constitution correctly. But we are happy that we have achieved our primary objective — this uncertainty has been removed. That is progress.”

State election officials feared that if the Supreme Court ruled that electors were free to defy the state, it could trigger enough defections to potentially upset the outcome in a very close race. During the argument in May, several justices said they feared it could create “chaos” in November if electors were not bound by their state or its laws.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.