‘Examine your heart’: Healing from turmoil, Wisconsin voters have a message for America

- Share via

KENOSHA, Wis. — All along the seven-mile road leading into Kenosha, no matter where you turn on the streets of its downtown business district, plywood scrawled with graffiti covers storefronts, bars and restaurants, community halls, government buildings. Even houses of worship.

Nothing has been left untouched by the outpouring of rage, despair and horror in the days after the shooting of Jacob Blake, a Black man, by police.

Yet the messages left by residents offer words of hope for a city that’s still trying to heal after civil unrest erupted here, in nearby Milwaukee and across the country following the shooting.

The phrase “Kenosha Strong” reads like a mantra in spray paint on too many boarded-up buildings to count.

There are quotes from the Book of John: “Love one another just as I have loved you.”

Each presidential election, outsiders home in on the importance of battleground states like Wisconsin in search of signs about the direction the country is headed in terms of its politics.

But the people of Kenosha seem to be having a more heartfelt conversation among themselves, one centered on the spiritual fortitude a society requires to survive one of its most turbulent periods in decades. It’s also focused on how hard it is to keep to the social contract in such a fiercely divided nation.

They’re trying to reassure one another that even here, where anger over Blake’s shooting continues to simmer and where the smell of charred wood from burned buildings still stings the nose, the idea of community is not a thing of the past.

The heart of downtown Kenosha, on the shores of Lake Michigan south of Milwaukee, was eerily empty on a recent hot afternoon — mostly due to so many shops closed because of the protests and the COVID-19 pandemic.

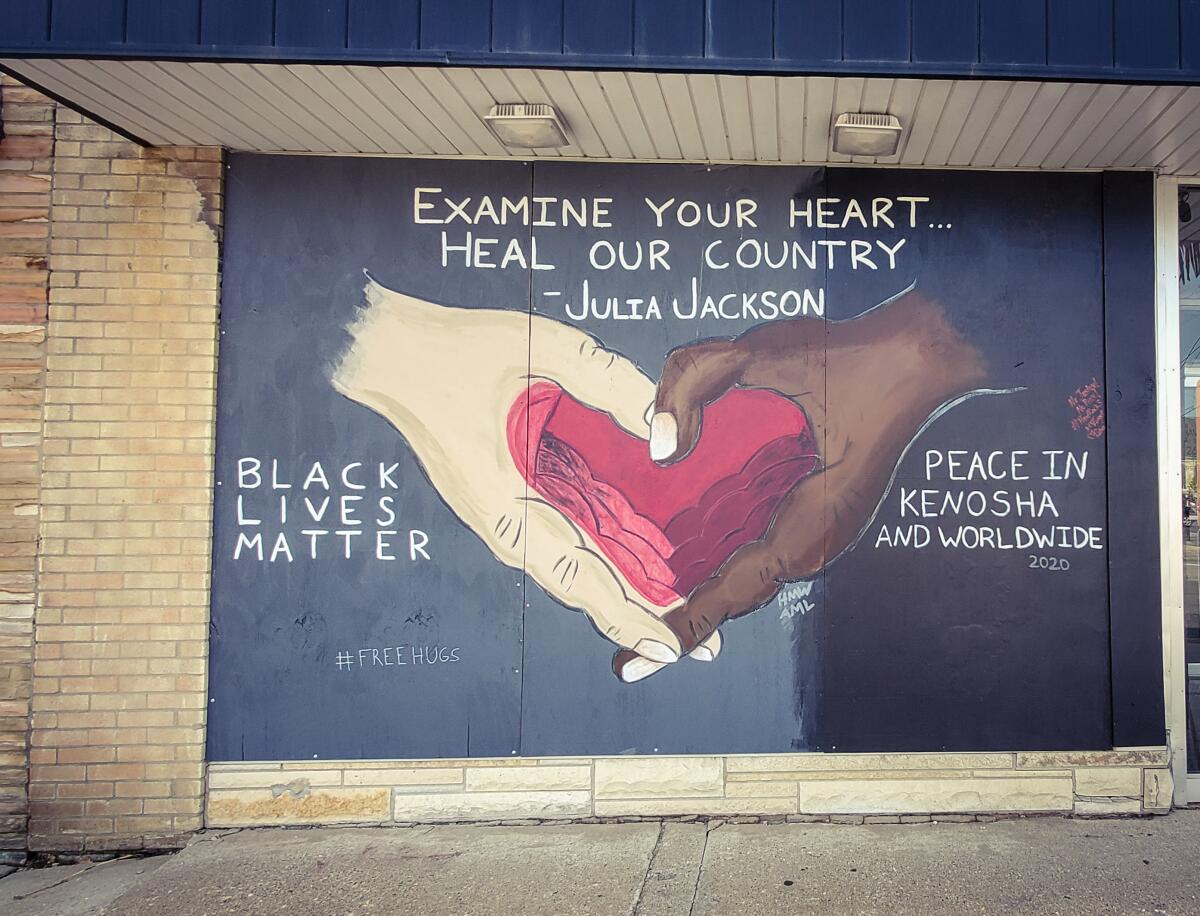

A mural on the way into town stood out for its quote from Blake’s mother, whose galvanizing words after his shooting starkly contrasted with President Trump’s us-against-them rhetoric.

“Examine your heart … heal our country,” it reads. “Black Lives Matter. Peace in Kenosha and worldwide.”

Many murals feature the city’s signature red lighthouse. Even that landmark, meant to ward ships away from danger on a lake so big it looks like an ocean, has been co-opted to offer guidance to residents.

“The light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it,” one quote reads, borrowing from another passage in the Book of John.

The camera crews that once provided around-the-clock coverage — of demonstrations, fires set by vandals and the shooting by a vigilante of two men who were protesting racism — have mostly gone. Both Trump and his Democratic rival, former Vice President Joe Biden, arrived in town, promised to help residents rebuild and then left

The Morgans and the Hanneses fly political colors on adjoining front yards that have remained a battlefield in the nation’s culture wars.

At S.J. Crystal’s, a menswear boutique on Kenosha’s main business strip, store manager Shad DeLacy sat in an old-school barber’s chair. His mind drifted far beyond the turmoil in his city and the upcoming election.

DeLacy, 43, said he’s done waiting for politicians on the left and the right to follow through on their promises to end racial inequality and help small-business people like him and the shop’s owner, Lewis Aceto, to thrive. The last time this independent voter cast a ballot in a presidential election was in 2008 for Barack Obama. He doesn’t plan to vote in November.

Friends and loved ones keep telling him that participating in the election could help shift the trajectory of a nation that feels dangerously off course. He isn’t convinced. “I don’t think my vote will matter, regardless of who wins,” DeLacy said.

On the plywood that covers the shop’s windows, someone had painted a Beatles-inspired mural of the lighthouse and a yellow submarine along with the words: “All we are saying is give peace a chance.”

Though DeLacy loves the idea of peace someday reigning across the land, at the moment he’s ready to give up on America.

Trump in his RNC speech skips a chance to promote racial healing and end police brutality.

DeLacy grew up in Kenosha. He says he was 16 when Aceto gave him his first job. He moved away but returned in 2018 to help Aceto run the boutique, and he plans to take it over someday.

The store, which has been around for 124 years under different owners, was spared from vandalism.

An auto dealership several blocks away wasn’t so lucky. It sits like a graveyard with about two dozen burned-out vehicles baking in the sun, displaying messages of their own.

“Kyle Rittenhouse — murderer,” someone spray-painted on one of the cars, referring to the teen vigilante who’s been charged with killing the protesters.

“What did our community do to deserve this,” the lot’s owners ask on a banner pinned to the outside of the scorched office.

On another car, someone painted a more loving message: a green heart.

For his part, DeLacy doesn’t want his city of 100,000 to be a symbol of America’s descent into chaos. But lately, he says, “it’s hard to trust anyone.”

He thought that Kenosha would be his future, that he’d join the ranks of entrepreneurs breathing new life into old industrial towns on the Great Lakes.

Now he intends to build up the shop, take over the business one day, train a new manager who can eventually run the daily operations — and then start packing.

“I’m trying to keep my head down and get through the next few years, and then I’m getting my Black ass out of the U.S.A. — I want to move to Belize,” DeLacy said. “It’s sad that that’s my goal.”

He wonders whether Americans are willing to live up to the principles of love, fellowship and mutual understanding displayed on so many surfaces in Kenosha.

Just then his boss, Aceto, walked in. They greeted each other like the best of friends, even though Aceto is a Trump supporter and DeLacy, who’s not aligned with either party, can’t stand the president.

Aceto, who is white, reminisced with DeLacy about when voting used to be “fun,” a special occasion in the positive sense when people at opposite ends of the political spectrum could still be civil to one another.

Kim Schmidt has been struggling to keep the faith, too. She works at Cardinali’s Bakery, a longtime business on the highway that leads into town.

Schmidt, 44, never thought she’d see the kind of unrest that took hold in Kenosha after the Blake shooting.

The bakery, like virtually every neighboring business, is boarded up, with the ubiquitous “Kenosha Strong” painted on the wood just below a vintage neon sign that advertises the “Golden Krust” of the shop’s baked goods.

“There’s tension, constantly, all the time,” Schmidt said. “You feel like you can’t even look a person in the eyes on the sidewalk because you don’t know what’s going to happen.”

Inside the store, standing in front of a piece of plywood scrawled with the words “Love is the answer,” Schmidt said she didn’t vote for Trump in 2016 but is considering voting for him in November. She just doesn’t know enough about Biden.

The president too often “says the wrong things,” Schmidt said, but she’s willing to believe that he’s a decent enough person with a big enough heart to deserve a second chance.

Farther north in Milwaukee — one of the most segregated cities in the country, where Black residents make up 44% of the population of 600,000 — people were less willing to give Trump the benefit of the doubt.

About 100 masked worshipers gathered under a white tent in the parking lot of Unity Gospel House of Prayer on the city’s mostly Black north side as a dozen others watched at a safe distance from inside their cars.

Pastor Marlon Lock was on a roll, telling his flock about “wickedness in high places.”

Lock didn’t have to mention Trump by name.

The approving nods and “Uh-huhs” in the mostly Black congregation showed they knew just who he was talking about.

They rocked gently to a live gospel band and raised their hands in prayer whenever Lock gave the word. The service took on the atmosphere of an old-time roadside revival down South.

Lock quoted from the Book of John and urged his audience to follow Jesus’ example by looking out for others, by helping the sick and oppressed.

“What you see here is what we need more of in the city of Milwaukee and not just here but all over — we have got to learn how to get along,” said Anthony Lee, a 40-year-old custodian who was still feeling uplifted after Lock’s sermon.

Lee said he regrets that some demonstrations have led to vandalism in Black neighborhoods that were already hurting, as well as violence between opposing protesters. “What kind of example are we setting for our kids for the future — hatred? Why hate one another?”

Kimberly Lock, the pastor’s wife and a minister in her own right, watched from inside her SUV.

Lock, 45, said that she’s not interested in declaring loyalty to one party but that she’s voted for Democrats almost exclusively in the past.

She plans to vote for the Biden-Harris ticket in November.

“Anything is better than what we’re experiencing now, because there’s so much racial violence, I think having a lot to do with communication that has trickled from the top down,” she said.

“I sense that if we have to deal with another term of the existing president, then we’re going to reach a boiling point — it’s going to come to a head where something is going to explode.”

Lock also never spoke Trump’s name, but she offered him some spiritual advice.

“My prayer would be that he not be selfish, that he considers others and that he thinks about the power that he’s been given to make this country better — because it’s a delegated authority. It’s not his.”

A few days later, the nation’s ability to withstand the tensions of the times was tested again when a grand jury in Louisville, Ky., declined to charge three police officers who had fatally shot Breonna Taylor, a Black woman whose name has become another rallying cry against police brutality.

Protesters took to the streets in Louisville, Ky., and Los Angeles after a grand jury declined to charge officers in the killing of Breonna Taylor.

A group of mostly of Black and white people in their 20s marched through Milwaukee that night, joined by a caravan of motorists honking their horns. Along the way, people stepped onto their porches and stoops to raise their fists in solidarity.

The marchers arrived at a mural of Taylor with the words “Say her name” printed under her likeness. Huddled in the darkness, they lighted candles in memory of a woman they didn’t know.

Some got down on their knees to pray and pour libations on the ground in Taylor’s honor. Others shouted to their Black ancestors before bowing their heads in sorrow because in their view, the dream of justice had once again been deferred. One man nearly choked up as he pleaded to anyone within earshot not to give up on the prospect that the United States will someday treat its Black citizens with respect.

The ceremony was its own appeal to basic kindness and decency, a challenge to Americans to do what the graffiti artists of Kenosha, the worshippers at the church and those gathered on this night had all called for in their own ways: to look to their better angels and view mercy — especially toward those who’ve been left to beg for it, such as Black people — as the ultimate expression of love.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.