Biden supporters flock from other states to door-knock in Arizona, where it matters

- Share via

PHOENIX — Alex Rosado hasn’t hugged his father in months, and he blames President Trump. Rosado said the president’s failure to contain the coronavirus pandemic has kept him away from his dad and made him want to work that much harder to make sure Trump loses the election.

So Rosado, a bellman in Los Angeles, left his home in his “guaranteed blue” state and relocated temporarily to Arizona, a battleground where he believes he can help defeat Trump.

Rosado, a member of Unite Here Local 11, had planned to take some time off from work before the election to register voters in the state, but the pandemic stalled his plans. So when the opportunity came to move to Phoenix in July and knock on doors for Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden, whom his union endorsed, he did not hesitate.

“There was no question I wanted to be here,” Rosado said on a September morning before another day of canvassing. “I want to make sure that I’m one of the people responsible for getting him out of office. ... What we’ve been going through — that’s not normal.”

In past presidential cycles, and even for Senate and gubernatorial races, residents of both parties have traveled across state lines to campaign. California GOP strategist Mike Madrid said he remembers droves of Northern California Republicans and Democrats taking multiday trips to Nevada to do outreach in 2016.

This election cycle, many campaigns and organizations shifted to mostly online outreach in an effort to slow the spread of the coronavirus. Though the Trump campaign never paused in-person outreach, Biden’s team followed public health guidelines and is only recently starting door-knocking in battleground states including Nevada, Pennsylvania and New Hampshire. Polling shows Biden is leading Trump in Arizona, which hasn’t chosen a Democrat in a presidential race since 1996.

Advocacy groups, labor unions and politically aligned organizations filled in by hiring canvassers in another battleground state, Arizona. Many are from California, whose residents also donate millions to Democratic and Republican candidates in competitive races in other states.

“Active campaign volunteers are smart enough to know California is not up for grabs in a presidential race, and if they want to help elect Joe Biden on the ground, they need to work in another state,” said Rose Kapolczynski, a Democratic campaign consultant. She added that although phone-banking is effective, the most persuasive form of campaigning happens at the doors.

“Person-to-person contact is still the most powerful way to engage a voter,” she said.

A look at where President Trump and Joe Biden stand on key issues in the 2020 election, including healthcare, immigration, police reform and climate.

In 2017, the Phoenix local of Unite Here — which represents workers in airports, hotels, restaurants and sports arenas — merged with L.A.-based Local 11 to combine strengths ahead of the 2020 election, communications director Rachel Sulkes said. In July, after it ran a small pilot program and hired an epidemiologist to offer guidance, the union started hiring canvassers, she said. Members are required to wear protective gear when door-knocking.

The moment also coincided with job losses for many L.A. members, Sulkes said, and by canvassing for the union, they earn an income and keep their health insurance. The union has more than 100 members from L.A. in Phoenix, making up a third of its canvassers, and some are regulars.

“We’ve had people who haven’t just come from this cycle, but were here in ’18 and ‘16,” she said, referring to Arizona’s competitive 2018 Senate race and the last presidential election. “We believe California is going to go blue. But, so what? That wasn’t enough in ’16. It’s not going to be enough now. And you can’t afford to put your head in the sand.”

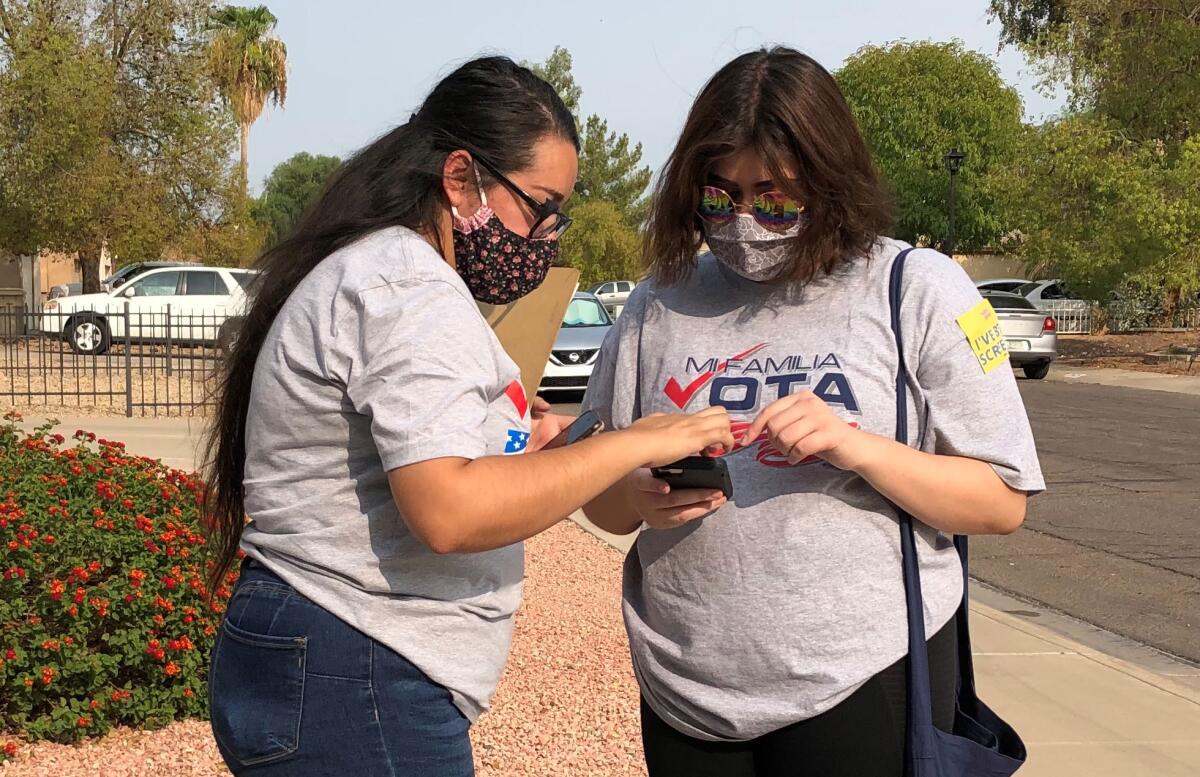

At Mi Familia Vota, a national Latino voter engagement group, a small number of non-Arizonans took extended leaves from their positions with the United Farm Workers to reach voters and register new ones in Maricopa County.

“These individuals are coming in solidarity to make a change,” said Eduardo Sainz, the Arizona state director for Mi Familia Vota. The organization has not endorsed former Vice President Biden, but it opposes Trump.

On a recent Friday, a canvasser named Victoria spent another afternoon in the desert heat, knocking on doors in Glendale, Ariz. She had traveled 1,000 miles to be there.

On one of her last stops, a woman came out wearing a face mask to greet her. Victoria asked the woman if she had a few minutes to complete a survey about the election.

The woman planned to vote for Biden, she said, because she wanted Trump out of office. “I just think he’s dangerous,” she said, giving the example of migrant children separated from their parents at the U.S. border.

Victoria nodded. Immigration was an important issue for her too, she told the woman, because Trump’s hardline stance on immigration could harm her family.

Where President Trump and Joe Biden stand on immigration policy, including DACA, refugees, asylum seekers, pathways to citizenship and deportations.

Victoria’s husband, a farmworker who has toiled in fields in Florida and Washington state, is undocumented. And every day, Victoria said, she is afraid of losing him. So Victoria, who did not want her last name published for fear that her husband could be deported, said she made the decision to leave her job with UFW, her home state of Washington, a Democratic stronghold, and most of her family, to do her part.

“If it means working 13 hours a day and being away from my family, then that’s what I’m going to do,” she said. She came to Phoenix with her oldest daughter and left her three other children with their father. “Even though it’s a sacrifice for a small amount of time, if we can win, it’s going to be worth it.”

Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric and policies affect voters everywhere, said Areli Arteaga, an Oregon resident canvassing in Arizona. “I had never felt the fear in our community like I have these last four years,” she said.

Arteaga said she understands how traumatic the Trump administration’s separation of migrant families is for the children. Her parents were deported when she was 5, during the Clinton administration, but she later reunited with them, she said. Coming to Arizona was an opportunity for her to campaign against Trump “so that our children don’t have to have that innocence taken from them,” she said.

“Our communities have been under attack, regardless of what part of the country we’re from,” said Arteaga, who spent her 27th birthday door-knocking in temperatures in the high 80s. “It doesn’t matter what ZIP Code you’re from, you’ve been impacted by this administration.”

José Flores, 23, drove the nearly 500 miles from Bakersfield to Phoenix the Friday before Labor Day. Flores is used to traveling, having worked on Julián Castro’s presidential campaign for a few months in Iowa. Originally from Immokalee, a small agricultural town in southwest Florida, he studied political science and economics in college and plans to work in politics long term.

Flores said he didn’t have anything keeping him in California, making it easy for him to travel. But there is a small sacrifice he’s making: His baby sister was born in May, and he hasn’t gone home to see her or his mother since then. He’s met her only over FaceTime, he said, but that’ll change once the election is over, he said.

“I’ll meet her in December,” he said, “when all this is said and done.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.