Activists brace for voter intimidation efforts on election day

- Share via

WASHINGTON — As a young lawyer for the New Jersey Democratic Party, Angelo Genova quickly realized something was amiss on election day in 1981.

“Our team was getting calls left and right,” he said. “A lot of it was a blur.”

In urban Black communities across New Jersey, large signs had appeared warning that polling places were “patrolled by the National Ballot Security Task Force.” Off-duty cops, some armed, wore armbands and demanded voters’ identification before they could cast ballots.

The task force was a Republican invention. Though no one could prove how many people were too intimidated to vote, the party viewed it as a success when its candidate, Thomas Kean, won by a 1,797 votes in a recount of more than 2.3 million ballots cast.

The Republican National Committee planned to run the same playbook in states around the country, but Democrats obtained a federal court order preventing them. The consent decree has limited the committee’s activities in every election since then — until now.

Armed right-wing groups are registering as poll watchers and planning to monitor voting places during the presidential election.

A federal judge allowed the order to expire two years ago, and the lack of legal safeguards against “ballot security activities” has Democrats and voting rights advocates bracing for Republican intimidation efforts on Nov. 3.

President Trump has urged his supporters to “go into the polls and watch very carefully,” and his campaign says it is recruiting a citizens’ “Army for Trump” to serve as volunteer poll watchers.

The effort is being run with the Republican National Committee, which deploys certified poll watchers to polling places alongside counterparts from the Democratic National Committee. Normally, additional volunteers are not allowed for fear of interference.

“The Republican Party has had a history of engaging in activities that are designed to diminish people’s participation rather than increase it,” said Genova, who still works as a Democratic Party lawyer in New Jersey.

Trump’s “rhetoric strongly suggests that the strategy is alive and well, and it has high potential to be manifest in this election,” he added.

Republican officials deny any plans to intimidate voters and argue that the end of the consent decree, which limited the party’s ability to participate in election security programs, puts them on equal footing with Democrats.

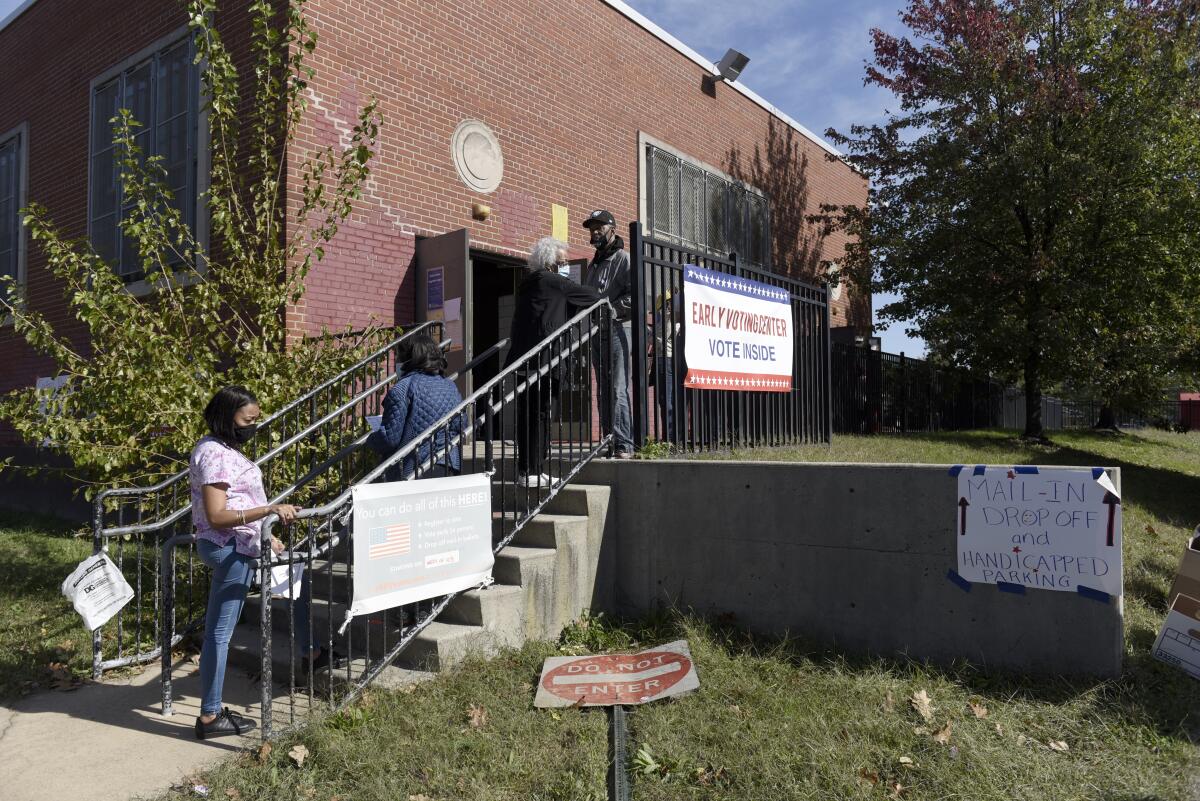

With two weeks until election day, long lines, administrative errors or computer glitches have slowed early voting in some precincts. But more than 28 million people had voted around the country as of Monday, a record, and no organized disruptions were reported.

Mandi Merritt, a spokeswoman for the Republican National Committee, said members of the Trump campaign poll watching operation are trained to be “respectful and polite” and to follow the law.

“The poll watching program is designed to ensure that no legally eligible voters are disenfranchised, that all votes are accurately and legally tabulated, and that voters are not confused about laws and procedures,” she said. “It’s about getting more people to vote, not less.”

That’s not the message from the Trump campaign.

“We all know that the Democrats will be up to their old dirty tricks on election day to make sure that President Trump doesn’t win,” Trump spokeswoman Erin Perrine says in a recruiting video for poll watchers and election day volunteers.

“We cannot let that happen. That is why our goal is to cover every polling place in the country with people like you.”

The president’s son, Donald Trump Jr., also sought to recruit poll watchers in a video posted on Facebook last month, urging backers to “enlist today” because “the radical left is laying the groundwork to steal this election from my father.”

“We need every able-bodied man, woman to join Army for Trump’s election security operation,” he says in the video. “We need you to help us watch them.”

Armed far-right groups and Trump’s rhetoric have voting rights groups and officials looking to prevent intimidation at polling places within the confines of state gun laws.

As part of its election reform efforts, Facebook recently announced it would ban poll watcher recruitment posts that use “militarized language or suggest that the goal is to intimidate, exert control, or display power over election officials or voters.”

A Facebook official said the rule would not be enforced retroactively, but that Trump Jr.’s video would be banned if posted again.

The president has warned — without evidence — about widespread fraud from absentee ballots and in-person voting, especially in urban areas controlled by Democrats.

In August, he suggested sending law enforcement officers to polling places. And, at last month’s presidential debate, instead of urging his supporters to remain calm if election results are delayed on Nov. 3, he urged them to “go into the polls” and “watch very closely.”

“The message was really clear — he’s encouraging his supporters to show up and intimidate voters,” Tiffany Muller, who heads the anti-voter-suppression activist group Let America Vote, told reporters on a conference call with the Democratic attorneys general of Wisconsin, Michigan and Nevada.

With early voting underway, Texas Republican leaders are waging a legal battle against voter rights groups.

Lynette Monroe, a Black Democratic voter, found out in 1981 what that could look like. According to the lawsuit that Democrats filed the following year, Monroe was stopped outside her polling place in Trenton, N.J., and questioned by members of the National Ballot Security Task Force.

“She was asked if she had her voter registration card and was told that if she did not have the card she could not vote,” the lawsuit said, even though cards aren’t required. Monroe left without casting a ballot.

The Trump campaign’s poll watching operation has already run into trouble this year.

Last month, election officials in Philadelphia turned away Trump campaign volunteers at satellite election offices, arguing that the sites were not official polling locations. Even if they were, the volunteers were not certified poll watchers.

A local judge sided with city officials on Oct. 9, ruling that the satellite offices were not polling places.

“We’re particularly concerned that these individuals are being deployed intentionally to communities that are home to large numbers of Black and Latino voters,” said Kristen Clarke, executive director of the nonpartisan Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law.

“The elimination of the RNC consent decree has resulted in open season for operatives who seek to exploit this moment,” Clarke said.

Even if the president’s threats don’t amount to intimidation, his words could have a chilling effect on some voters, activists say.

“The threat itself is generating fear and can be intimidating to voters,” said Wendy Weiser, vice president at the Brennan Center for Justice, a public policy institute at New York University Law School.

In theory, she noted, polling places should have adequate protection. Election officials can call law enforcement to remove people who disrupt voting, and voters can call nonpartisan hotlines to get legal help.

Historically, the right to vote in America has always been contested, said Kate Masur, an associate professor of American history at Northwestern University.

“There’s never in American history been a full-throated commitment by all Americans to the idea that all people who are eligible to vote should vote, and then be encouraged to vote,” Masur said.

For nearly a century after the Reconstruction era ended in 1877, white people in numerous states used lynching and other violence, threats and intimidation, and bureaucratic means to disenfranchise Black citizens.

Until the federal Voting Rights Act was passed in 1965, state and local governments passed legislation, including poll taxes and literacy requirements, that made it nearly impossible for millions of Black men and women to register to vote or cast their ballots.

Republican efforts to close polling places, limit mail service or restrict the number of ballot drop boxes are an outgrowth of those dark times, said Lorraine Minnite, a political science professor who specializes in voting rights at Rutgers University in Camden, N.J.

“You do it that way under the guise of law and procedure, rather than possibly illegal thuggery on the streets,” she said. “It’s less risky that way, and more effective if the outcome is more broadly applied.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.