Republicans call the COVID-19 relief bill a ‘liberal wish list.’ Democrats are owning that

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Republicans call the massive COVID-19 relief package making its way through Congress a “liberal wish list.” Increasingly, Democratic lawmakers and the Biden administration have chosen to own that.

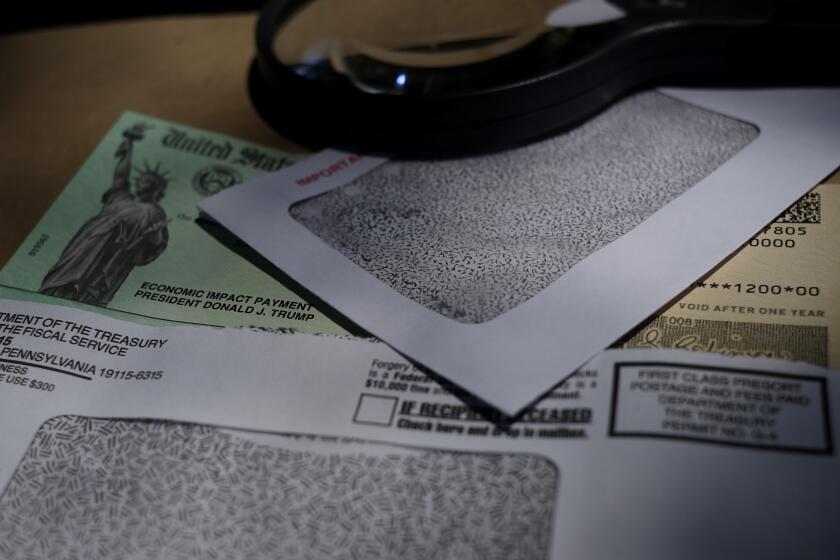

One measure of the bill’s sweep is a host of provisions Democrats have long sought — on topics including health insurance premiums, child care and pensions — that would amount to major pieces of legislation on their own. As part of the nearly $1.9-trillion package, however, they’ve gotten little public attention, overshadowed by debate over who should receive $1,400 direct payments and whether the bill should increase the minimum wage.

For weeks as the bill moved through Congress, administration officials emphasized President Biden’s openness to bipartisan negotiations. Now, with the measure’s congressional journey almost finished — the House is expected to vote on final passage Wednesday — the White House’s tone has shifted. Officials are more willing to crow about achieving Democratic goals.

The relief package is “one of the most consequential and most progressive pieces of legislation in American history,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki said Monday.

On Tuesday, Brian Deese, head of the White House’s National Economic Council, tweeted a list of less-publicized items in the bill that address homelessness, school meals, public transit and Native American concerns, among other topics.

Republicans hope the size and sprawling nature of the measure will, over time, boomerang on Democrats. The GOP has been nearly unanimous in criticizing it as too costly and likely to cause inflation.

Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, for example, has broken with his party on some issues — one of a handful of Republican senators to do so. But on the COVID bill, he has stuck to the party line, calling it “massively excessive.”

House Republican leader Kevin McCarthy of Bakersfield denounced the bill in a floor speech as “the single most-expensive spending bill ever.”

“Almost every one of this bill’s 592 pages includes a liberal pipe dream that predates the pandemic,” McCarthy said.

Democrats, however, see little downside in delivering on long-promised goals. The bill aims squarely at the middle- and lower-income Americans whom Biden’s campaign promised to help, they note. And although many of the goals predate the pandemic, COVID-19 has made them more pressing, they argue.

They’ve been encouraged by surveys that have consistently shown strong support for the legislation. A poll released Tuesday by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center indicated that 70% of Americans are in favor of the package, with 28% opposed. Despite the unanimous opposition of GOP members of Congress, 41% of registered Republicans surveyed said they favored the bill, and 57% opposed it. Support in the GOP was strongest among those who call themselves moderates and those with lower incomes.

The fact that even many of the less-debated provisions in the bill are consequential bolsters their case, Democrats say.

“When lesser-talked-about provisions still have the power to make major, material differences in the lives of those who are struggling at the hands of this pandemic or those who have started from steps behind, that’s when you know you are on the right path,” Rep. Richard E. Neal (D-Mass.), chair of the House Ways and Means Committee, said in a statement.

A closer look at what’s in the COVID-19 economic relief bill, including when the $1,400 checks would arrive and who would get unemployment.

The legislation marks a sharp contrast to the main economic bill passed during the Trump years: the 2017 tax cut.

Both measures had similar price tags. But the Republican bill showered nearly half of its benefits on households with incomes in the top 5% — those who were making about $308,000 or more in 2017. Backers said that approach would spur economic growth. The economy had a growth spurt in 2018, but by 2019, growth returned to roughly the same level as before the tax bill.

The Democratic bill, by contrast, would send about 70% of its benefits to those making $91,000 or less — the bottom three-fifths of the nation in terms of income distribution, according to a new analysis by the Tax Policy Center, a nonpartisan Washington think tank. Benefits for families make up about half of the cost of the legislation.

For those in the lowest fifth — with earnings of less than $25,000 — the legislation would increase take-home income by 20%, the analysis shows.

The direct relief checks provide a big part of that flow of money. Another major source is the bill’s expansion of federal aid to families with children, a measure that would cut child poverty nearly in half. Backers in Congress have doggedly pursued that goal for nearly two decades.

The measure, which would apply for one year, would cost roughly $110 billion, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Biden said last week that he favored efforts by some congressional Democrats to make the changes permanent, which they’re expected to push for later this year.

Another provision would give more middle-class Americans help with the cost of health insurance under the Affordable Care Act — the first expansion of the 2010 healthcare law, widely known as Obamacare, after years of Republican-led repeal efforts.

The expansion “checks a big item off the Democrats’ agenda for reinvigorating the Affordable Care Act,” said Larry Levitt, executive vice president for health policy at the Kaiser Family Foundation. “It’s not the sum total of President Biden’s healthcare agenda, but it’s a significant down payment.”

Roughly 29 million Americans stand to benefit from the first substantive federal expansion of Obamacare since 2010.

The current law helps people pay for premiums when they purchase insurance on the Obamacare marketplaces. But those subsidies apply only to those with incomes up to four times the federal poverty level, or about $51,000. Those earning more have to pay the full cost of premiums, except in a few states, including California, that partially subsidize them.

Under the new law, people could get help if premiums cost more than 8.5% of their incomes. According to a Kaiser Foundation analysis, most of the benefit would go to those with incomes between $51,000 and $100,000, especially people in their 50s and 60s, who tend to have higher insurance costs.

For many, the savings could amount to hundreds of dollars a month.

The provision, which would cover the next two years, would cost about $34billion, the budget office estimates. As with the child tax credit, the administration and congressional Democrats probably will try to make it permanent.

Still another part of the law would pump $24billion into a fund to stabilize the child-care industry, which lost about 200,000 jobs last year, according to a recent report from researchers at UC Berkeley.

Even before COVID, “this is a sector that struggled,” said Lea Austin of Berkeley’s Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, “but it’s been devastated by the pandemic.”

Child-care centers have faced higher costs for cleaning supplies and protective gear, she said, even as the pandemic has cost many parents their jobs and the ability to pay for care. In California, 1 in 5 child-care providers reported in July that they had missed at least one mortgage payment, Austin said.

Biden’s bill would provide $24billion to keep child-care facilities afloat, including money to help pay their workers, who make an average of under $12 an hour nationwide.

The bill would also expand the existing tax credit that families can use to offset the cost of care for a child or dependent, raising the amount of the credit and making it available to more people.

“It’s going to plug a hole that’s really been gushing over the last year,” Austin said.

Who are President Biden’s Cabinet members and what are their backgrounds?

The legislation would also break a decade-long logjam in Congress over the fate of pension plans that cover over 1 million union workers, retirees and their surviving spouses. That includes hundreds of thousands of Teamsters drivers, as well as miners, grocery and hotel employees and musicians whose pension plans were battered by the Great Recession and changes in their industries.

The change involves multi-employer pension funds, set up decades ago in trucking, coal mining and other unionized industries. As employment declined and many companies went out of business, their unionized workers’ pension plans started heading for insolvency. The federal Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., which provides a partial backstop for pensions, lists about 300 plans as being in critical condition.

The new law would provide grants to shore up the pension plans, enough to pay expected benefits for the next 30 years, said John Murphy, vice president at large of the Teamsters. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the cost at $86billion.

Democrats have pushed for nearly a decade for a federal rescue, but the effort repeatedly stalled as Republicans attacked what they referred to as a taxpayer bailout of generous pensions negotiated by unions.

“The world changed” when Democrats won the presidential election and a razor-thin majority of the Senate, Murphy said. “This is a giant, huge, enormous step toward resolving this problem.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.