Supreme Court rules California farms can keep union organizers off private land

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court on Wednesday struck down part of a historic California law inspired by Cesar Chavez and the farm workers union, ruling that agricultural landowners and food processors have a right to keep union organizers off their property.

The justices by a 6-3 vote said the state’s “right of access” rule violates property rights protected by the Constitution, which states private property shall not be “taken for public use without just compensation.”

Writing for the court, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. said “the access regulation is not germane to any benefit provided to agricultural employers or any risk posed to the public...The access regulation grants labor organizations a right to invade the growers’ property. It therefore constitutes a per se physical taking,” he wrote in Cedar Point Nursery vs. Hassid.

He cited as precedents a pair of California cases. One ruled for the owner of a beachfront home in Ventura who objected to giving the public access to the shore and a second from 2015 which ruled for a grape grower from Fresno who objected to giving his grapes to a government-sponsored cooperative.

“The upshot of this line of precedent is that government-authorized invasions of property — whether by plane, boat, cable, or beachcomber — are physical takings requiring just compensation,” Roberts said.

The three liberal justices dissented. They described the rule as a regulation, not a taking of property.

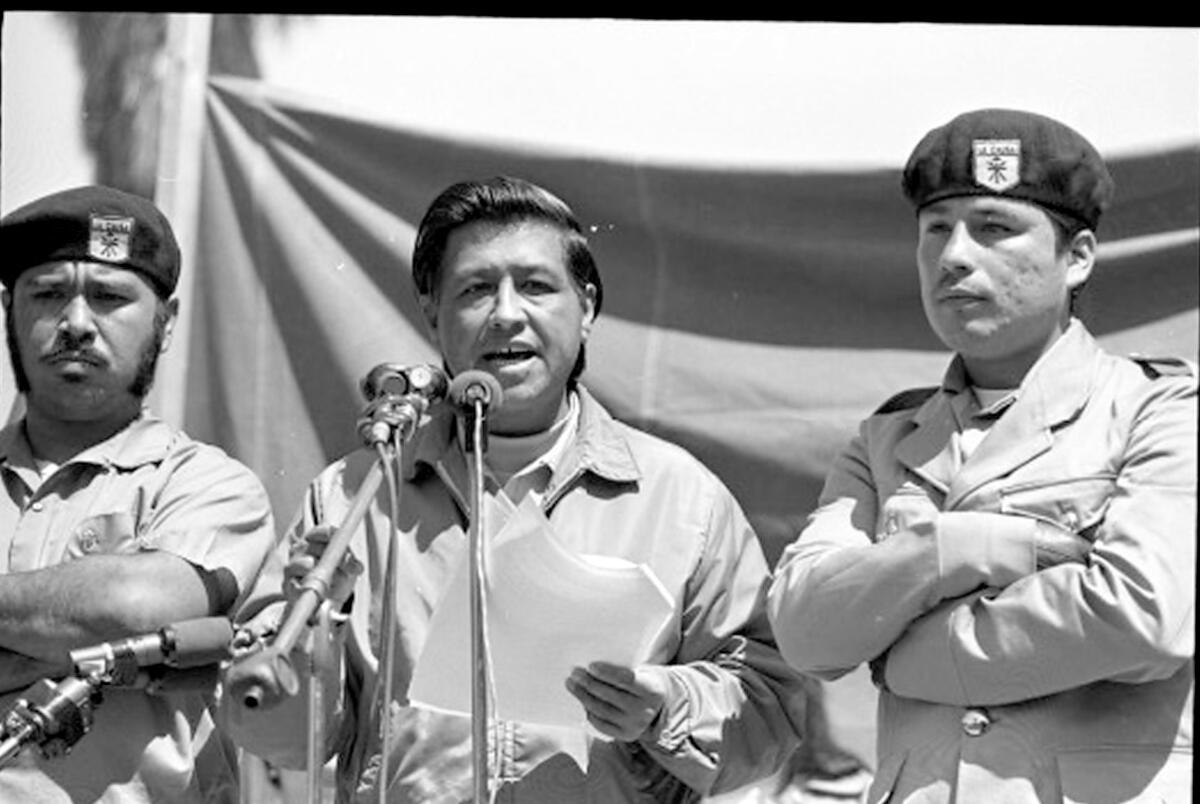

The California Legislature in 1975 became the first in the nation to extend collective bargaining rights to farm workers. Months later, a new agricultural labor board adopted the “right of access” rule to allow organizers to seek out those who were working on farmland.

Earlier this year, the state’s lawyers said the rule was still needed because farm laborers often worked in remote areas and were not fully aware of their rights to join a union.

It has come under attack in recent years by agribusinesses that have called it a “union trespassing” rule that violates their property rights.

A lawyer for the Pacific Legal Foundation, which represented the farm owners, cheered the ruling as “a huge victory for property rights.” It “affirms that one of the most fundamental aspects of property is the right to decide who can and can’t access your property,” said Joshua Thompson, a senior attorney for the group, based in Arlington, Va..

Karla Walter, a director of employment policy for the liberal Center for American Progress, called it a major setback for union organizing.

“Today the Supreme Court’s conservative majority overturned nearly a half-century of progress for California’s farm workers, who have struggled to exercise their right to bargain for decent wages and to protect their health and safety,” she said. “Reaching farm workers — the overwhelming majority of whom are Latinx and migrant workers — where they work is critical to protecting their rights and interests.”

The case decided Wednesday began in 2015. The owners of the Fowler Packing Co. in Fresno, which produces grapes and citrus fruit, refused to allow union organizers onto their property.

A few months later, union organizers entered a strawberry packing plant near the Oregon border and disrupted the work, according to Mike Fahner, owner of the Cedar Point Nursery.

The two companies then joined in a lawsuit seeking to have the California union access regulation declared unconstitutional. They lost before a federal judge and the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco, but the Supreme Court voted to hear their appeal.

Lawyers for the Pacific Legal Foundation representing the farm owners argued the Constitution “forbids the government from requiring you to allow unwanted strangers on to your property.”

In defense of the rule, California officials called it a temporary regulation of property, not a taking of the grower’s land. Union organizers may enter a farm for one hour before the start of the workday or for an hour at the end of the day.

The state’s lawyers said the rule is similar to federal and state laws that allow meat and poultry inspectors to go into packing plants or health and safety inspectors to visit warehouses, manufacturing plants or construction sites.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.