In Ohio House special elections, progressives take a loss, Trump scores a win

- Share via

In a defeat for the party’s left wing, Democratic primary voters in Ohio on Tuesday picked an establishment-backed candidate over an ally of progressive hero Bernie Sanders to fill a vacant House seat.

Shontel Brown, a local Democratic official who was backed by party leaders including top allies of President Biden, won the primary in a special election to replace Democrat Marcia Fudge, who left her Cleveland-area House seat to join Biden’s Cabinet.

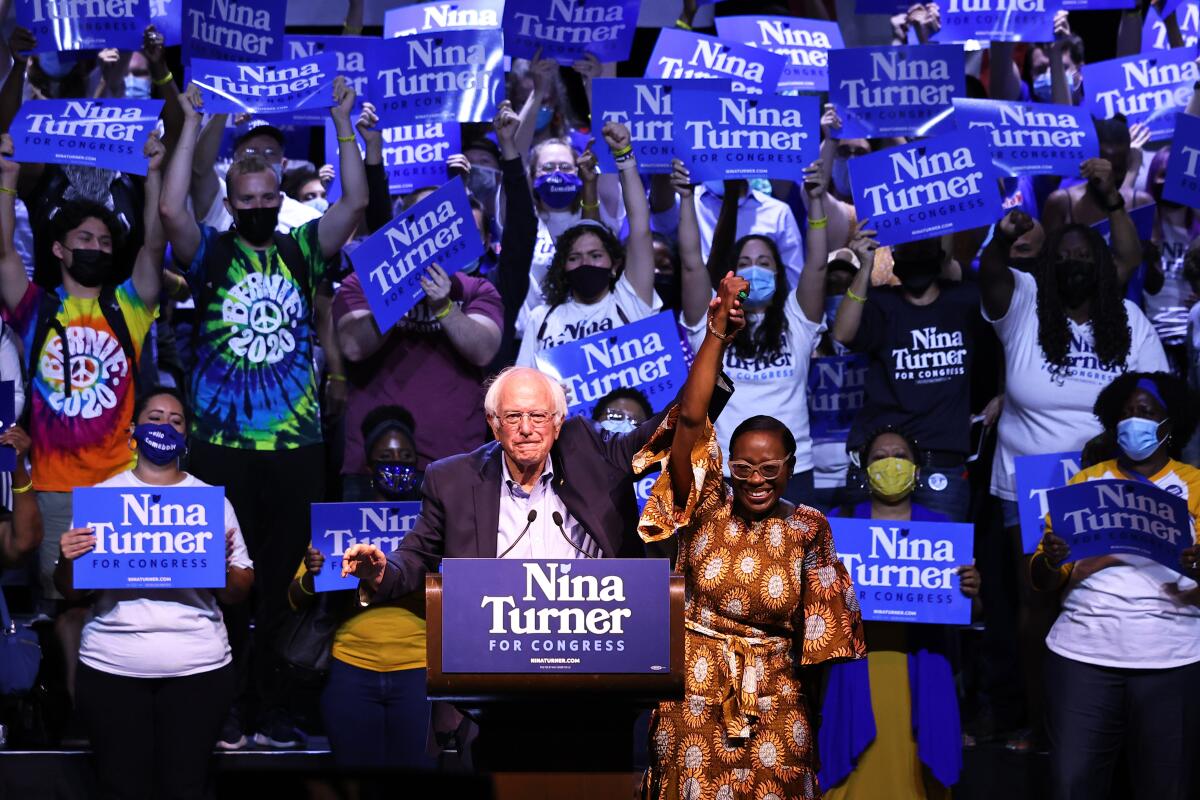

Brown defeated a large field of rivals, including her strongest opponent, Nina Turner, a pointed critic of Biden who gained prominence as co-chair of Sen. Sanders’ 2020 presidential campaign and drew endorsements from a who’s who of national progressive leaders.

Turner had started the campaign with a big lead because she got into the race early, was well known nationally and in the district, and had a big fundraising advantage. But Brown overtook her rival by gathering support from the local party establishment and national Democrats including Rep. James E. Clyburn of South Carolina, a powerful Biden ally, and Hillary Clinton.

Brown may have been a better ideological fit than Turner for the district, which favored Clinton over Sanders by a 2-to-1 margin in the 2016 Democratic presidential primary.

Brown’s primary win is a boost for moderate Democrats who have been in increasingly testy tussles with progressive activists and gives a new voice in Congress for voters who are more hungry for calm pragmatism than for the passionate populism that animates Sanders’ followers.

“People are looking for some stability,” said Jeff Rusnak, a Democratic political consultant in Cleveland who was allied with no candidate in the race. “People are tired and worn out after the last four or five years.”

Turner in her concession speech blamed an influx of what she called “evil money.”

“I am going to work hard to ensure that something like this doesn’t happen to a progressive candidate again,” she said. “We didn’t lose this race. Evil money manipulated and maligned this election.”

In another Ohio special election primary Tuesday, Republican voters picked a little-known candidate backed by former President Trump among a wide field to fill an open House seat, sparing Trump a potentially bruising political setback.

Mike Carey, a coal industry lobbyist, won the GOP primary in a Columbus-area district, an outcome that helped the ex-president stave off a potential second blow that would have called into question the value of his endorsements. Last week, a candidate he backed in a Texas special House election was defeated.

The Cleveland- and Columbus-area special election primaries were in districts so dominated by one party that the primary victors are nearly certain to win the fall general election.

Special elections are often quirky, with low turnout and buffeted by local dynamics, but these two have been watched nationally because they reflect the shifting ground of American politics in the wake of Biden’s victory over Trump in 2020.

“These primaries represent the new tensions that we have seen in both political parties,” said John C. Green, director of the Ray C. Bliss Institute of Applied Politics at the University of Akron. “Both the Democratic and Republican coalitions are unstable right now.”

In legislative and political arenas, Democrats are grappling with what kind of party they are becoming under Biden, who during the 2020 campaign cast himself as a transitional party leader who would prepare the way for a post-baby-boom generation of leadership. After a period of relative peace between progressives and moderates earlier this year, the factions have been hurling increasingly pointed barbs over how far the party should move to the left.

While many Democratic leaders in Congress have embraced a bipartisan infrastructure bill, some progressives have objected to what Biden considers a signature achievement because it did not include more for low-income families and gave too much ground to the GOP. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) criticized a Democrat leading the group that crafted the compromise for “choosing to exclude members of color from negotiations and calling that a ‘bipartisan accomplishment.’”

The infrastructure agreement also taps into emerging splits within the GOP: Many Senate Republicans — including Minority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky — support it. But Trump, who failed to enact a promised infrastructure bill while he was president, is virulently opposed to the bipartisan deal. He said Republicans were “looking weak, foolish, and dumb” by giving a “big win” to Democrats that could help them in the 2022 election.

In Ohio and other GOP primaries this year, Trump is trying to extend his sway over the party by making a slew of endorsements. Some establishment-oriented Republicans worry his picks will not be the strongest candidates for general elections in swing states.

Ex-President Trump rewards allies and punishes enemies with endorsements. He meets this week with Wyoming Republicans running against Rep. Liz Cheney.

Trump was stung by the defeat of his endorsed candidate in Texas last week when turnout was abysmally low. That undercut his allies’ arguments that the former president’s endorsement is a silver bullet and that his involvement in the 2022 midterm election will drive Republican turnout.

In the Ohio contest, Trump endorsed Carey in June, saying in a statement: “He will be a courageous fighter for the people and our economy, is strong on the Border, and tough on Crime.”

The Republican-dominated district previously held by GOP Rep. Steve Stivers, where white voters make up the overwhelming majority, reaches from the Columbus suburbs into a wide swath of rural precincts. Trump’s endorsement there was a risky bet because Carey was one of 11 Republican candidates in the primary, including state Rep. Jeff LaRe, who was endorsed by Stivers, and Bob Peterson, a state senator endorsed by the antiabortion group Ohio Right to Life PAC.

In a late push, Trump spoke in a telephone rally for Carey on Monday night, and alluded to the high political stakes — for him — in the outcome of this obscure special election: “A lot of people are watching this one. It’s a big deal.”

The electorate of the Cleveland-area congressional district, which stretches south to include much of Akron, is made up of a majority of Black voters. It also includes a substantial Jewish population. The Democratic primary featured a big field of contenders, but Brown and Turner were the clear front-runners in fundraising and endorsements.

Both women are Black, and their competition underscored a generation gap among Black politicians. Brown was endorsed by the political arm of the Congressional Black Caucus, a group dominated by an older generation of more moderate lawmakers who were key to Biden’s victory in 2020. But there is a growing cadre of younger Black Democrats in the House who are much more progressive. Many of them — including Reps. Ayanna Pressley of Massachusetts, Cori Bush of Missouri and Mondaire Jones of New York — have broken with the caucus group endorsement and backed Turner.

Many prominent Democrats — and deep-pocketed political interest groups — from across the country took sides in the costly, increasingly nasty contest.

“You don’t have enough fighters” in Congress, said Sanders (I-Vt.), one of several allies who traveled to Ohio to campaign for Turner. “You don’t have enough people who have the guts to take on powerful special interests.”

Cornel West, a political activist, author and intellectual, also campaigned for Turner, saying: “We can say to some of our brothers and sisters who are part of the corporate wing of the Democratic Party with their milquetoast neoliberalism: We want vision, integrity; we want a focus on the least of these, the poor, the working-class, everyday people.”

Clyburn campaigned for Brown, and was joined by House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Bennie Thompson of Mississippi, who took a dig at Turner’s confrontational style.

“You don’t need somebody who will go in there and talk about tearing the place up,” said Thompson. “What we need is somebody who will be a good Democrat, work with the Democratic leadership and support Joe Biden as president.”

Biden did not weigh in on the primary, but he loomed over the race because of Clyburn’s endorsement of Brown. Fudge also stayed out of the primary, but her mother endorsed Brown.

Brown’s supporters — including a pro-Israel political action committee opposed to Turner because she has not supported unconditional aid to Israel — spotlighted an infamous 2020 quote from Turner when, in an interview with the Atlantic, she compared the prospect of voting for Biden to “eating a bowl of s—.”

Turner argued that her critics care too much about her style and not enough about the poor.

“Fighting for justice is messy; it is radical, it is in your face,” she said at a prayer breakfast in Akron on Monday. “When you fight for justice you might not always use the prettiest words.”

Turner’s campaign denounced Brown for accepting campaign contributions from Republicans including Robert Kraft, owner of the New England Patriots and a prominent Trump supporter.

“Shontel Brown: It’s hard to tell whose team she is on,” said a Turner ad.

The Brown campaign responded by portraying her as a unifying leader and strong Biden ally: “Unlike Nina Turner, who has attacked and insulted Democrats like President Biden at every turn, Shontel Brown has built a coalition of Democrats, independents and yes, even some Republicans, who want to elect someone to Congress who will work with Joe Biden to deliver an economic recovery to Northeast Ohio and stop gun violence.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.