- Share via

WASHINGTON — In the 25 years that U.S. Rubber Recycling in Colton, Calif., has been grinding up old tires to create new products, its sales have never ballooned so fast as during the COVID-19 pandemic.

As countless fitness centers closed, and millions of people began exercising at home, online demand for the company’s rubber mats and personal gym flooring soared.

But the company had a problem: finding enough workers to fill all the new orders.

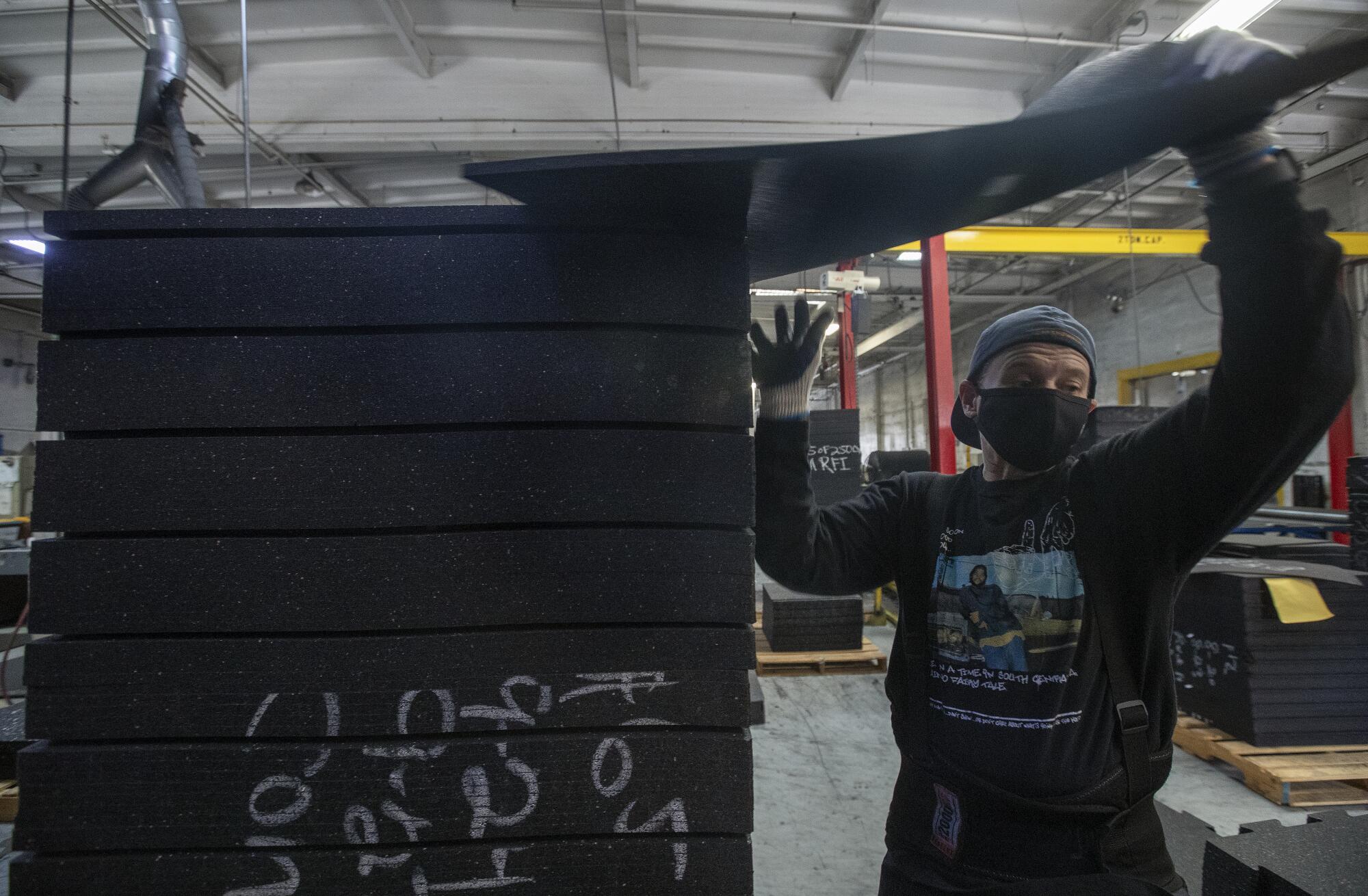

That’s where U.S. Rubber’s long practice of hiring former felons paid off as people like Thomas Urioste came into the picture. In March, the 50-year-old Wrightwood, Calif., man was released from federal prison after serving nearly 10 years. He was living in a halfway house and, like many former prisoners, finding it hard to get a new start.

So when he heard that U.S. Rubber was hiring, he hurried to apply. And instead of being rejected as those with criminal records often are, he got hired practically on the spot.

Six months later, with his salary bumped up to $17 an hour, Urioste can hardly believe how far he’s come. “They took a chance on me, gave me some responsibilities pretty fast. They let me run this [$200,000] machine,” he said last week. “It feels pretty good because they trusted me.”

All across the country, as the economy surges and employers struggle to find enough workers, former prisoners like Urioste are finding a sliver of a silver lining in the dark cloud of the pandemic.

This summer, U.S. employers reported an unprecedented 10.9 million job openings. That was equal to more than one job for every unemployed person in the country.

In response, a growing number of companies are beginning to tap into a huge, largely ignored labor pool: the roughly 20 million Americans, mostly men and many unemployed, who have felony convictions.

A tiny fraction of businesses, including U.S. Rubber Recycling, have long made a point of hiring ex-convicts. And in recent years, California and about a dozen other states have sought to remove some of the discrimination against these job candidates by banning employers from directly asking applicants about criminal records.

But the laws have proved fairly easy to get around. Employers now frequently make background checks for criminal records and probe gaps in applicants’ work histories. Once past problems come to light, the door slams shut.

“Of all people who face challenges in the labor market, those with records are at the end of the queue,” said Shawn Bushway, an economist based in Albany, N.Y., and criminologist at Rand Corp.

Things tend to get a little easier during times of very low unemployment. What’s different this time is that the nation’s jobless rate is not close to rock bottom; it was 5.2% in August. (The jobs report for September will be released Friday.)

And yet today’s unusually severe labor shortages, reflecting both short- and long-term forces, seem to be opening up opportunities for ex-offenders. Some analysts think that may prove more lasting than in the past.

“Are we in a world where employers really have to start doing something differently?” Harry Holzer, a public policy professor at Georgetown University, asked, noting that businesses already were grappling with declining labor force growth, including the aging of Baby Boomers.

“Maybe, maybe there’s a potential for some win-win — good for these guys and their families and good for employers and the economy.”

Researchers have found that with each successive year that formerly incarcerated people remain free without committing another crime, the likelihood of their returning to criminal activity declines. And after five to 10 years, that person has no higher probability of committing an offense than someone with no record. Holzer thinks employers are often overly fearful.

More companies are coming to the conclusion that they cannot afford such fears.

Harley Blakeman, chief executive at Honest Jobs, an Ohio-based company that matches employers with people with criminal records, said that in the last few months, seven Fortune 500 companies have signed on as partners, including manufacturer Owens Corning, packaging giant Ball Corp. and the distribution firm Arrow Electronics.

Blakeman said a key challenge is revamping how background checks can disqualify those with convictions without regard to the job.

At Honest Jobs, Blakeman said, he hired seven people this year, most of them with criminal records, including a woman who applied for an executive assistant position that required handling finances. Because her past included two fraud charges, he said, she was instead offered a job working with employment applicants.

“I told her I cannot give you this job in particular because it’s too risky. That’s good business sense. But what happens is, the person with the fraud charge applies for a warehouse job and gets weeded out. That doesn’t make sense,” Blakeman said.

He founded Honest Jobs in late 2018 after his own struggles finding work while he was on parole after serving 14 months in state prison in Georgia.

While economics are prompting more companies, particularly large ones, to look at workers with convictions, there are countervailing forces holding back such hiring.

Many ex-felons, like others on the margins of the labor force, have little education and few skills. And after years in which violent crimes dropped, 2020 saw an increase in violence, led by murders and assaults.

“With [violent] crime rates rising, I think there will be some places where it will be more challenging salesmanship to try to reintegrate ex-offenders. The picture becomes a little bit more untidy,” said Nicholas Eberstadt, a political economy scholar at the American Enterprise Institute and author of “Men Without Work.”

Already, people on parole or probation after incarceration, who number more than 4 million, face all kinds of employment and occupation restrictions. Those with felony records are barred from getting licenses for some medical occupations and barbering and beautician services, for example, and convictions may curtail driver’s licenses for trucking and delivery work.

Melvin Price Jr., 41, of Long Beach was paroled last September after serving 16 years in federal prison. As part of his release, he said, he couldn’t work or “congregate” within 300 feet of a dispensary because of a prior criminal offense. And he has a 10 p.m. curfew, which meant he couldn’t apply for late-night or graveyard jobs at warehouses and other places that were hiring.

In November, Price found work at Chrysalis, a Los Angeles-based nonprofit that helps the homeless and entrenched unemployed. And last week, through Chrysalis, Price landed a job doing landscape work for Caltrans. He’ll make about $3,000 a month.

“I promised that if I ever got another chance, I’d make the most of it,” said Price, whose life as a youth spiraled downward after his mother was murdered in 1992.

While Chrysalis has seen a near-tripling of inquiries from employers this year, there’s no sugarcoating the challenges.

At U.S. Rubber Recycling, where about half of the company’s 65 employees are ex-felons, Chief Executive Jeff Baldassari says the turnover rate for those with convictions is about 25% higher than for others without criminal records.

“They stack up very well when it comes to skills,” he said. “Where the gap lies is the attrition rate. The challenge they have with emotional stability in their lives is critical.

“Many don’t have life-skill lessons — how you deal with relationships. You can’t control their family life and who they hang out with,” he said.

Baldassari, for his part, tries to use the eight hours these employees work for him to provide training, build teamwork and avoid what he called a “fishbowl syndrome,” in which certain workers feel they’re being watched and judged because of their records.

The company works closely with staff at halfway houses, and he has hired a psychiatric rehabilitation counselor.

Thermal-Vac Technology Inc. in Orange, which also routinely brings on people with past criminal offenses and addiction problems, holds weekly Alcoholics Anonymous meetings inside the company and invites parole officers to visit.

“You can hedge your bets, reduce some of the risks,” said Heather Falcone, Thermal-Vac’s chief executive.

Baldassari says his hiring practices have been good for his business, especially now when the competition for labor is stiff, and he says the stories of the workers speak volumes about what productive work can mean for turning their lives around.

Carlos Arceo, 39, was hired a little more than two years ago after 10 years in prison in Arizona. Since then, he’s been promoted four times. When the pandemic-induced boom arrived, Arceo became supervisor of a new second shift.

He says he still meets with the company counselor every week or two, but nowadays it’s less about himself than about managing the people under him.

“A lot of the hires are fresh out of prison, just like I was,” he said, adding with a laugh that at the company, it’s not just used tires that are recovered and find new use. “We’re giving people a second chance too.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.