Column: Can Biden and Xi talk their way out of a slide into conflict?

- Share via

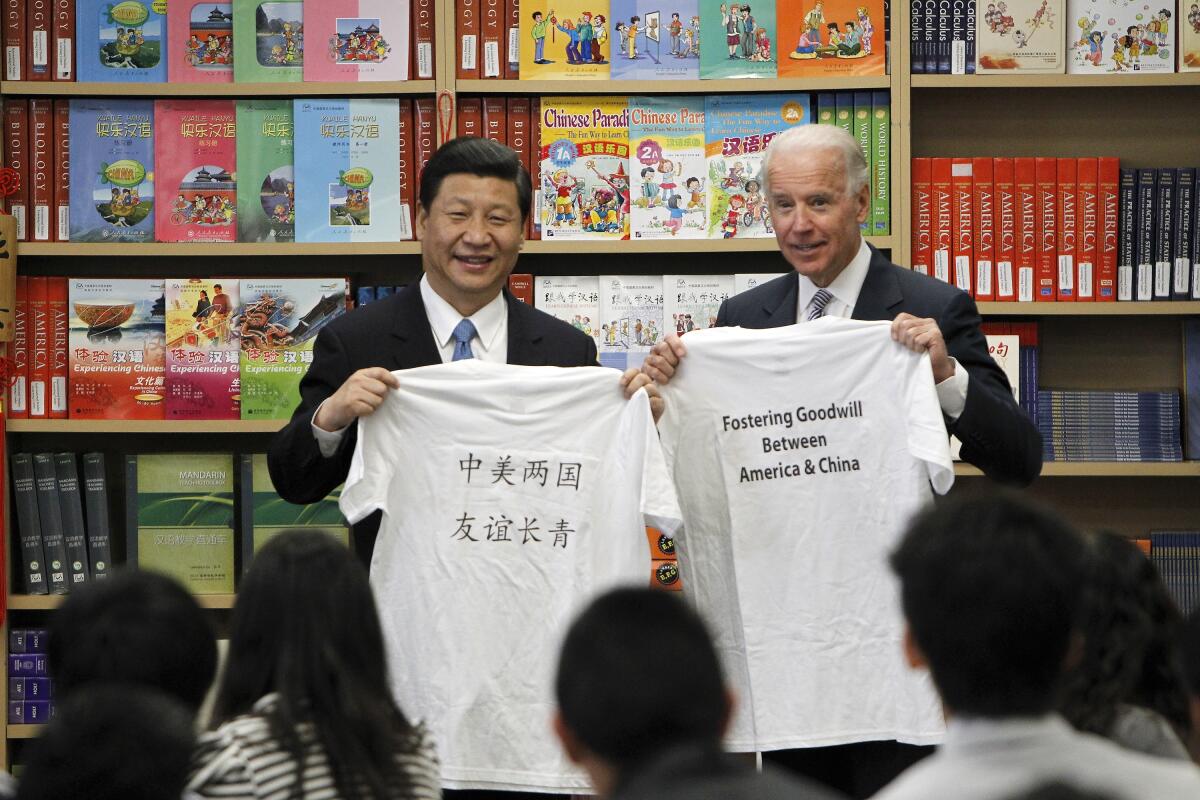

WASHINGTON — Inflection points in global politics don’t often announce themselves in advance. But the complex and dangerous relationship between the United States and China may reach such a moment Monday, when President Biden and his Chinese counterpart, Xi Jinping, hold a virtual summit meeting.

For almost a decade under three U.S. presidents, the two superpowers have slid into more frequent confrontation as an increasingly assertive China has collided with the United States and its allies.

The frictions flared during the administration of President Obama after Xi, an ambitious nationalist, rose to power in Beijing. President Trump sharpened the conflict, imposing large tariffs on Chinese goods and accusing Xi’s government of unleashing the COVID-19 pandemic.

When Biden came to office, many in both countries expected tensions to ease — but the new president kept Trump’s tariffs in place and made it clear that he wanted to negotiate new rules to constrain China’s behavior.

In March, a meeting in Alaska between Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken and Chinese foreign policy chief Yang Jiechi began with a bitter exchange of accusations over trade and human rights.

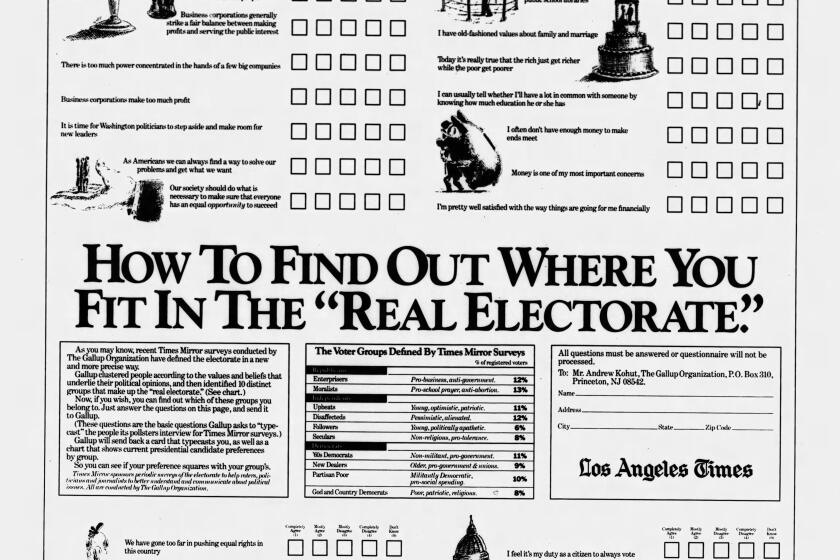

Study focuses on splits within each party’s coalition: Views of Trump and economics for GOP, speed of change and policy toward crime for Democrats.

Months of friction followed. U.S. officials criticized China for bullying smaller nations in Asia and repressing its Muslim Uyghur minority. China’s air force increased its sorties near Taiwan, the self-governing island that Beijing claims as part of its territory; the U.S., Britain and Canada sent warships through the Taiwan Strait in a show of allied force.

The U.S. commander in the Pacific warned that China might attack Taiwan by 2027; Biden said he had an obligation to help the island defend itself.

Pentagon officials warned that China was accelerating its military buildup, putting it on pace to quadruple its nuclear weapons to 1,000 warheads by 2030.

The United States strengthened its alliances in Asia, including a deal to supply nuclear-powered submarines to Australia as part of a new military pact dubbed AUKUS.

It looked and sounded like an inexorable march toward conflict.

Biden aides say some of the friction was necessary. It was important, national security advisor Jake Sullivan said last week, to “show that China’s efforts at pushing other [countries] around will not ultimately be successful.”

The confrontation offered Biden one more benefit: It helped win bipartisan support in Congress for two parts of his domestic economic program, his $1.2-trillion infrastructure bill and a $250-billion technology spending measure that quickly became known as the “China bill.”

His pitch wasn’t subtle.

“If we don’t get moving, they’re going to eat our lunch,” the president told senators in February, referring to the competition with Beijing.

Soon, some members of Congress were pushing the president and the administration to get even tougher on China, especially in regard to Taiwan.

It began to look as if the administration had stumbled into the story of the sorcerer’s apprentice: It had created a new, more hawkish consensus on China, but the anti-Beijing fervor was threatening to spiral out of control.

“They are digging a hole that’s going to be difficult to get out of,” a former top official in the Obama administration told me. “If this turns into a zero-sum situation, one in which one side must prevail and the other side must be defeated, that will make it a self-fulfilling prophecy” — a march toward war.

By September, Biden and his aides began to stop digging.

“We are not seeking a Cold War or a world divided into rigid blocs,” the president told the United Nations.

All the United States wants, Sullivan said last week, is “to set the terms for an effective and healthy competition … with guardrails and risk-reduction measures in place to ensure that things don’t veer off into conflict.”

The U.S. hopes it can cooperate with China on climate change, nuclear proliferation and other issues, he added.

It was a good sign last week when the United States and China issued a joint plan to slow global warming at the U.N. climate change conference in Scotland — a last-minute effort whose scope was modest but whose effect was to spare both Xi and Biden from blame if the summit failed.

This week’s meeting between the two presidents, their first full-scale summit, could cover a long list of issues: nuclear proliferation, trade talks, easing military tensions in the Taiwan Strait, even visa regulations.

But administration officials are carefully setting the bar low.

The aim, a Biden aide told me, is “to maintain open channels of communication, make clear U.S. intentions and priorities, and responsibly manage the competition between our countries.… This is about setting the terms of an effective competition.”

In other words, to borrow a term from the Cold War with the Soviet Union, the goal is to make “peaceful coexistence” possible between two incompatible governments.

Even that won’t be easy. The frictions that have built over the last decade make that clear.

“Stiff competition” between economic, diplomatic and nuclear superpowers won’t ever be simple to manage, and one summit meeting isn’t going to end their disagreements. But it can begin the process of defusing them, and that would be an important step.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.