- Share via

WASHINGTON — Like a football team that scripts its first several offensive plays prior to kickoff, President Biden entered office in January having already sketched out a template for his first several months: He would start with a sweeping relief package aimed at addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, then pivot to a massive economic recovery package.

This White House has executed that game plan with a discipline not seen since, well, before his predecessor took office. The final piece of Biden’s ambitious agenda is up in the air. And the political scoreboard is grim. His approval rating is a paltry 42%, according to a recent NPR/Marist poll, clear evidence of the public’s frustration with the president’s inability to eradicate the pandemic and ease their concerns about the economy.

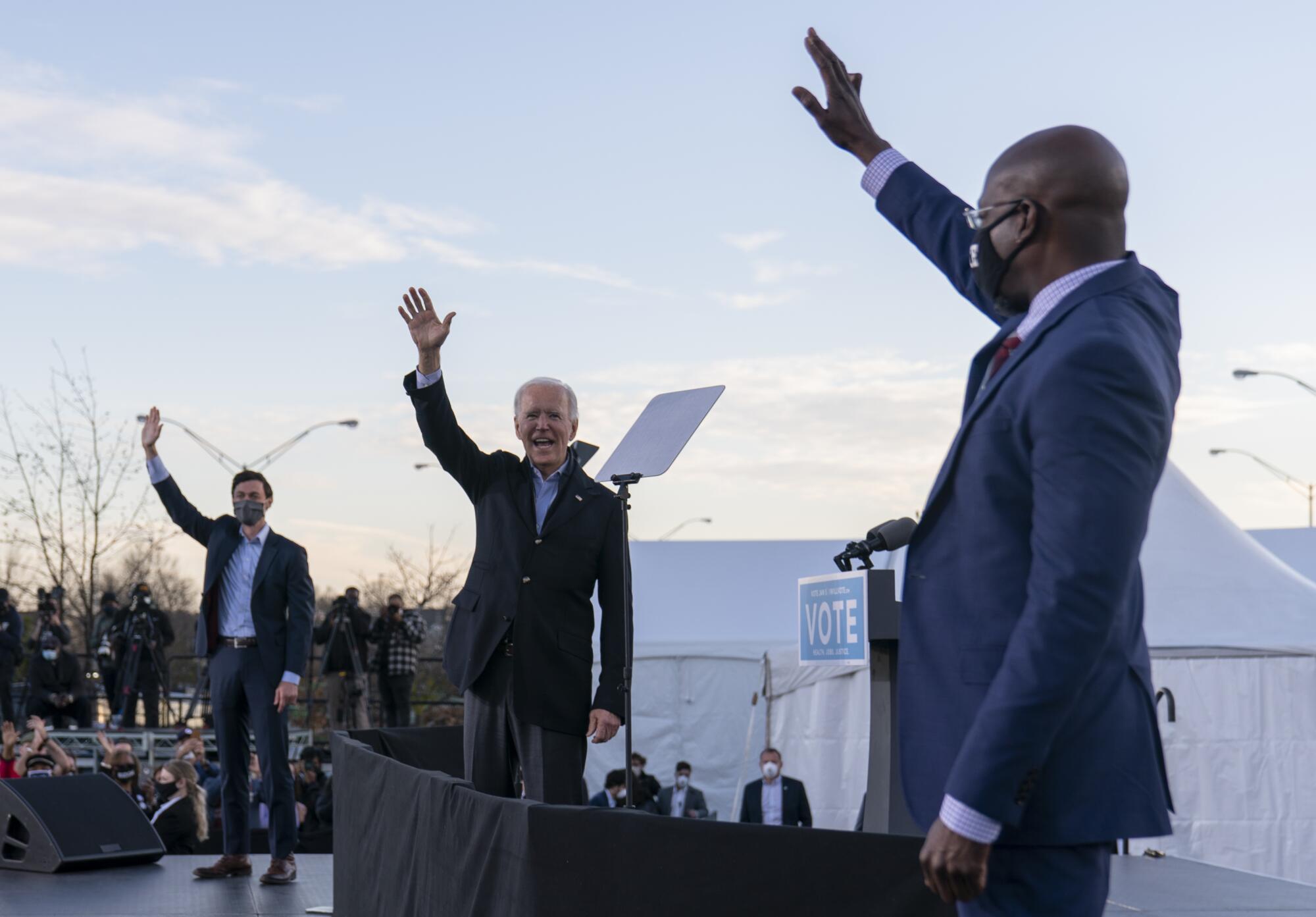

With the unexpected boon of a Senate majority following a Democratic sweep in two Georgia runoff elections just weeks before he took the oath of office, Biden succeeded in March in enacting the first piece of his agenda, the sweeping $1.9-trillion American Rescue Plan, which authorized a massive infusion of federal aid aimed primarily at working families grappling with the pandemic.

With his approval ratings still above 50% as summer arrived, the president looked to build momentum, splitting his recovery agenda into two bills: an infrastructure package he believed could win bipartisan support and a second bill with enhanced benefits for working families he planned to pass with only Democratic support.

Biden is trying to work with Republicans while keeping Democrats united. It’s a tricky balancing act, but he has the experience to pull it off.

Biden signed the $1.2-trillion infrastructure bill at the White House last month, touting overdue investments in roads, bridges, railways and pipelines. He hailed the achievement during a ceremony on the South Lawn as evidence that “Democrats and Republicans can come together and deliver results.”

Unfortunately for the president, the bipartisan cooperation on infrastructure looks like an isolated incident. The second bill, already scaled back significantly, stalled for weeks in the evenly divided Senate, where Sen. Joe Manchin III (D-W.Va.) has been reluctant to back the package, leaving Biden short of the 50 Democratic votes he needs to pass the $1.75-trillion measure. The package was further imperiled when Manchin announced Dec. 19 he would vote “no.”

Biden’s challenges have extended far beyond Congress.

The pandemic he declared independence from in July persists with the emergence of new variants. Although some 200 million Americans are fully vaccinated, 40% of the country has opted against getting the shot, mostly in heavily Republican areas that have resisted the president’s pleas and vaccination mandates despite a rising death toll.

Despite a record drop in the unemployment rate, which in December stands at 4.2%, and a rise in wages, inflation has spiked, sparking anxiety among a broad swath of consumers. Biden has taken actions to ease inflation, but results could be months away.

The latest numbers on rising inflation are a reminder of how President Biden’s first year has become bogged down with economic challenges.

Biden capped his first trip abroad in June by meeting in Geneva with Russian President Vladimir Putin, hoping a frank dialogue would stabilize the relationship. So far, it’s not clear the pressure has yielded results. Hackers in Russia keep launching ransomware attacks, and Putin is amassing troops on his country’s border with Ukraine, raising alarms in capitals from Kyiv to Washington.

In August, the ostensibly popular decision to withdraw U.S. forces from Afghanistan blew up in Biden’s face. That’s when the Taliban took control of the country — something Biden said just weeks prior was unlikely — and left the administration scrambling to airlift thousands of vulnerable Afghans out of the country. It was the first major misstep for a president who had spent months showcasing his administration’s competence and focus.

As the Taliban takes unfettered control of Afghanistan, major challenges await, including at the Kabul airport, the scene of the West’s last stand.

Biden is struggling with other problems that are not easy to fix. His administration hasn’t yet slowed an unanticipated influx of migrants at the southern border, and presidential rhetoric has been no match for a state-level Republican assault on voting rights and the rampant polarization tearing at the country’s social fabric.

Democratic activists are at wits’ end that their party, despite controlling the White House and Congress, has struggled to muster a response to the voting restrictions being passed in Republican-controlled states predicated on former President Trump’s persistent lies suggesting that the 2020 election was stolen. The refusal by Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) to change the Senate filibuster rule to allow Democrats to pass voting rights legislation with just 50 votes appears to have taken the main federal remedy off the table.

Liberals are also nervous that the Supreme Court, controlled by a 6-3 majority of conservative justices, seems poised to strike down the landmark 1973 Roe vs. Wade decision that established a woman’s right to an abortion.

Looking ahead, Biden will probably spend the year leading to the midterm election trying to focus voters on what he has achieved, not what remains undone. He’ll tout his efforts to make infrastructure improvements and stabilize the economy. Aides believe Americans will appreciate his accomplishments if inflation is tamed and the second recovery bill — and its tax credits and subsidies for child care, elder care and preschool — becomes law.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.