- Share via

WASHINGTON — They were running out of time and needed a Hail Mary.

Joe Biden had won the electoral college vote in the 2020 presidential election. And with less than three weeks before Congress was set to certify the results on Jan. 6, 2021, allies of then-President Trump met with him in the Oval Office to discuss taking desperate measures.

Following dozens of failed challenges to the election in court, and with plans to ask lawmakers to throw out some state results, Trump operatives including former national security advisor Michael Flynn drafted an executive order intended to allow the administration to seize voting machines. To the horror of White House lawyers, the president was being urged to sign it.

Named in two drafts of the order to help justify the seizure was Coffee County, Ga., where officials had refused to certify the results of the presidential election — a clear indicator there had been fraud, Trump’s allies argued. A last gasp in the frantic efforts to keep Trump in office, the eventual breach of election systems in the rural southeastern Georgia county would go on to become a critical part of the sweeping racketeering indictment filed in Atlanta in August alleging a broad conspiracy by the former president and 18 co-defendants.

Together, depositions and other court documents, testimony to the House Select Jan. 6 Committee and public statements made by those involved provide one of the most comprehensive accounts to date of what happened in Coffee County — and the role it played in the final days of the futile endeavor to ensure Trump remained in the White House.

As the now-infamous Dec. 18 Oval Office gathering devolved into a chaotic, hours-long shouting match between Trump operatives and the White House lawyers, Trump attorney Rudolph W. Giuliani stepped in to wave the president off from signing the executive order. “Voluntary access” to a Georgia voting system was in the works, Giuliani told Trump, according to testimony before the Jan. 6 committee, making the order unnecessary.

It was part of a new strategy, Giuliani said on former Trump advisor Stephen K. Bannon’s podcast the next day, to use evidence obtained from voting machines to circumvent Republican governors — like Brian Kemp of Georgia — who were unwilling to continue investigating allegations of fraud. “Just push ’em aside,” Giuliani said.

It’s unclear whether Giuliani noted where in Georgia that access would be provided. But shortly before the contentious Oval Office meeting, he had met with an unnamed “whistleblower” a block away at the storied Willard InterContinental Washington. Giuliani associate Bernard Kerik paid for that person’s room.

The identity of the whistleblower has not been made public.

Staying at the Willard at that time was Coffee County GOP leader Cathy Latham. She later told a court she’d gone to Washington to tour a museum, but refused to say whether she‘d met with anyone during her visit.

Weeks later, on Jan. 7, 2021 — after rioters were cleared from the Capitol and the vote had finally been certified — a surveillance camera captured what appeared to be Latham escorting a team, reportedly sent by Trump attorney Sidney Powell, into the Coffee County elections office to access voting machines.

Powell pleaded guilty last week to six misdemeanor counts of conspiracy to commit intentional interference with performance of election duties, part of a deal that requires her to testify and provide evidence for prosecutors.

Latham can be seen on surveillance video taking a selfie with a member of the group, which included Atlanta bail bondsman Scott Hall, who was indicted by Fulton County Dist. Atty. Fani Willis on Aug. 14 alongside Latham, Powell and former Coffee County elections supervisor Misty Hampton. Hall pleaded guilty in September to five misdemeanor counts of conspiracy to commit intentional interference with performance of election duties.

Several unnamed and unindicted alleged co-conspirators are also mentioned in the 98-page indictment in connection with the Coffee County effort, which appears to be the only successful attempt by Trump allies to access federally protected election equipment that the former president was told about while he was in office.

::

Allegations of fraud in Coffee County were brought to Trump operatives one week after the Nov. 5, 2020, election, when Hampton and a fellow Board of Elections member contacted the campaign about a presentation the elections supervisor had given to warn that bad actors could “manipulate” the state’s Dominion Voting Systems machines.

In the presentation, Hampton pointed to a routine process in elections administration called adjudication, in which a panel typically composed of representatives of both the Republican and Democratic parties reviews hand-marked ballots that are not clear to try to determine the voter’s intent. She argued that adjudication was open to fraud, and was filmed demonstrating how she believed an elections administrator could flip votes during the process.

In a deposition for Curling vs. Raffensperger, an unrelated case over Georgia election machine security that uncovered the Coffee County breach, Trump campaign staffer Robert Sinners said that he had forwarded the Coffee County information to campaign lawyers, but that he thought Hampton’s allegations were “a lot of speculation.”

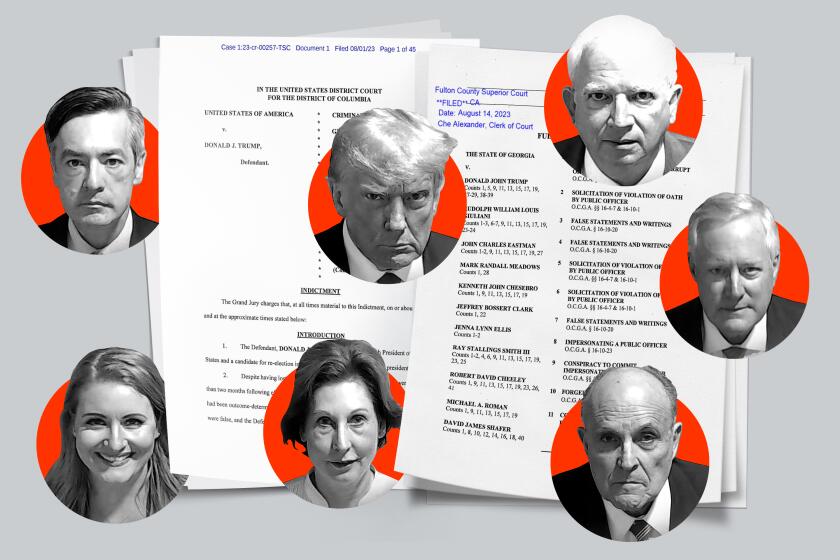

The four indictments of former President Trump have thrust into the spotlight names that are largely unknown along with many that are familiar to the public.

The next month, on Dec. 3, 2020, Giuliani testified before a Georgia legislative subcommittee looking into possible election fraud. Hall also testified.

The hearing took place as the state was conducting a third recount of ballots. The Coffee County Board of Elections had refused to certify its results for that recount, citing an “inability to repeatedly duplicate creditable election results.”

On Dec. 7, 2020, Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, a Republican, certified that Joe Biden had won Georgia, with a subsequent investigation by his office determining that a 51-vote discrepancy cited as alleged fraud by Coffee County officials was the result of human error.

Despite Raffensperger’s certification, a lawyer working with the Trump campaign filed a lawsuit in state court on Dec. 12, seeking to throw out Georgia’s presidential election results, citing Coffee County’s refusal to certify the electronic recount. The plaintiff in that suit was Shawn Still, a fake elector also charged in the Fulton County indictment.

Latham, then chairwoman of the Coffee County GOP, traveled to Washington a couple of days later. She said in her deposition from the unrelated election security case that she was there with a tour group. But she invoked the 5th Amendment right against self-incrimination when asked whether she‘d met with anyone else while in Washington, and again when asked about a Dec. 17, 2020, text she sent that said, “I am in D.C. right now and am about to meet with IT guys.”

Latham’s attorney, William Cromwell, did not reply to a request for comment from The Times about her previous statements.

Kerik, a former New York City police commissioner, told the Jan. 6 committee that he had paid for an unnamed Georgia “whistleblower” to stay at the Willard hotel — where Trump’s allies were crafting eleventh-hour plans to persuade state and federal lawmakers to throw out votes and hand him the election. Latham has testified that she stayed at the Willard during her trip.

“They wanted to bring this person to meet [Giuliani] to discuss some issue that was going on in Georgia, and we made arrangements for them to come,” Kerik said of the unidentified person he called a whistleblower.

The plans to prevent Congress from certifying Biden’s win hinged on proving evidence of fraud in the election, something Trump’s team was not able to do.

So with time running out, his allies drafted proposed executive orders — dated Dec. 16 and Dec. 17, 2020 — that would have directed the Defense secretary or Department of Homeland Security to seize voting machines, and called for the appointment of a special counsel to investigate the election. As part of the justification for the orders, both drafts stated that Coffee County had “identified a significant percentage of votes being wrongly allocated contrary to the will of the voter,” and had therefore “refused to certify its result.”

The Coffee County reference did not appear in the draft executive order presented to Trump in the Oval Office meeting on Dec. 18. That version would have allowed Homeland Security to seize state election machines and voting data. According to testimony provided to the House Jan. 6 committee by multiple people who attended the meeting, it devolved into a shouting match between Trump allies and White House lawyers over whether the president had the legal authority to make such an order and how the public would react.

In an effort to keep Trump from signing the order and naming Powell as special counsel, Giuliani promised that the campaign would soon have access to election machines in Georgia, former White House Staff Secretary Derek Lyons told the Jan. 6 committee in a deposition.

The ReAwaken America Tour, a pro-Trump religious roadshow, has become known for promoting Christian nationalism and right-wing conspiracy theories.

“When [Giuliani] showed up at the meeting, his position was that I believe the campaign was going to secure voluntary access to machines, and that that would be the way to prove up the compromise of the machines,” Lyons said.

Powell corroborated that account in her Jan. 6 committee deposition.

“I think maybe there was an effort by some people to get something out of Georgia, and I don’t know what happened with that, and I don’t remember whether that was Rudy [Giuliani] or other folks,” she testified, saying that she wasn’t aware of the details. The Fulton County indictment, however, alleges Powell’s assertions that she had no knowledge of the effort were false. Powell did not return a request for comment from The Times.

Giuliani told the Jan. 6 committee that he didn’t recall mentioning getting access to machines.

“I don’t remember that exactly, but it could be that we were negotiating with one of the boards for access to some of the machines,” he testified, according to a transcript of his deposition for the panel.

Committee investigators tried to refresh his recollection by citing a Dec. 22, 2020, email from Powell to Trump’s chief of staff, Mark Meadows, which stated: “Georgia machine access promised in meeting Friday night to happen Sunday has not come through.” (Meadows and Giuliani are both charged in the Fulton County indictment, but not in connection with the Coffee County efforts.)

Giuliani’s memory was sharper when he appeared on the podcast “Bannon’s War Room” on Dec. 19, 2020 — a day after the raucous Oval Office meeting. Giuliani told Bannon that he had “a big project working in Georgia right now,” noting that he was proceeding without the cooperation of Kemp, the state’s governor, and working “right around his back.”

“He doesn’t know what the heck is going on,” Giuliani said of Kemp. “[Trump’s team] met pretty much on and off all day yesterday, and starting this morning there’s a completely different strategy. The strategy is going to focus a great deal on some evidence we have about some of these machines that could throw off these states in a matter of maybe a one- or two-day audit. I think we can get these accomplished, despite the resistance and the cover-up of the Republican governors.”

Associates of Giuliani working out of the Willard hotel noted in a “strategic communications plan” dated Dec. 27, 2020: “We Have 10 Days To Execute This Plan & Certify President Trump!” The memo cited Hampton‘s video presentation and Coffee County’s refusal to certify its election results, saying they supported allegations of fraud and should be presented to House and Senate Republicans as reasons to halt election certification on Jan. 6.

::

Giuliani returned to Georgia on Dec. 30 to speak to the state Senate subcommittee looking into potential election fraud — led by then-state Sen. William Ligon, a Trump supporter. Also testifying were Latham and her attorney, Preston Haliburton, who described Latham to legislators as a “whistleblower.” Kerik said Ligon and Haliburton had arranged to have an unnamed whistleblower speak to Giuliani in mid-December. Latham has not stated she is the whistleblower.

Latham said in her Curling vs. Raffensperger deposition that she first heard from Hall shortly after that state Senate testimony. The bail bondsman had asked for an introduction to Hampton.

Meanwhile, according to court documents, Hampton and Coffee County elections board member Eric Chaney were working on a written invitation for the Trump team to come to Coffee County. Powell provided a copy of a short note dated Dec. 31, 2020, in a filing this Sept. 27 in the Fulton County case.

“I will be speaking with my board, and per Georgia Law I do not see any problem assisting you with anything y’all need [in] accordance to Georgia Law. Y’all are welcome in [the county elections] office anytime,” the unsigned letter states. Powell named the authors as Hampton and Chaney in her court filing.

Douglas Frank has given dozens of speeches alleging voter fraud in California and across the country, and has helped create teams aimed at disrupting state election systems.

On Jan. 1, 2021, court documents show, an employee of Atlanta data forensics firm SullivanStrickler, forwarded a text message to her colleagues from “Katherine,” who had some news to share: “Hi! Just handed [sic] back in DC with the Mayor. Huge things starting to come together! Most immediately, we were granted access — by written invitation! — to the Coffee County Systens [sic]. Yay!”

In a Sept. 27 court filing, Powell identified the sender of the text as Katherine Friess, a lawyer working with Giuliani who participated in efforts to access machines in other states. Friess did not respond to requests for comment from The Times.

A privilege log produced in a Georgia defamation case against Giuliani — brought by election workers whom he falsely accused of mishandling ballots — shows that Friess forwarded a document to Kerik and Phil Waldron, a retired Army colonel who worked closely with Giuliani, on Jan. 1, 2021, titled “Letter of invite from Coffee County GA.” The next day, she forwarded another document to Giuliani, Kerik, Waldron and two others titled “Ligon letter to DJT requesting DHS cyber audit,” according to a list of records Kerik fought to withhold in the defamation suit.

Discussions about accessing Coffee County machines continued that Jan. 6.

At 4:26 p.m., moments after Trump released a video asking rioters to leave the Capitol, Hampton texted Chaney about a request to visit the Coffee County elections office: “Scott Hall is on the phone with Cathy about wanting to come scan our ballots from the general election like we talked about the other day. I am going to call you in a few.”

Chaney invoked the 5th Amendment when asked about the text in a deposition for the Curling case. But Hampton confirmed in her deposition that she was speaking about Cathy Latham and said that Chaney had directed her to allow the election systems to be copied. When asked whether he‘d authorized access to the elections office, Chaney again pleaded the 5th. A Coffee County elections board spokesperson told investigators that Chaney did not have the authority to give that direction.

At 7:27 p.m., the SullivanStrickler team began discussing in their text thread which employees would go to Coffee County in the morning. Representatives of SullivanStrickler, which is not charged in the Fulton County indictment, have said under oath that they believed they had permission to copy the machines.

As Congress prepared to regroup from the mob’s attack to certify the election, Giuliani pleaded with Republican senators for more time.

“I know [Congress is] reconvening at eight tonight, but the only strategy we can follow is to object to numerous states and raise issues so that we get ourselves into tomorrow — ideally until the end of tomorrow,” he said in a voicemail left for a senator around 7 p.m., according to the federal indictment of Trump and others in connection with efforts to overturn the 2020 election.

But the GOP senators didn’t provide the assistance Giuliani hoped for. At 3:41 a.m. on Jan. 7, 2021, hours after the attack on the Capitol ended, Vice President Mike Pence certified that Biden had won the election.

The Coffee County plans were already in motion.

Latham was seen on video security footage later that day escorting the SullivanStrickler team into the Coffee County elections office along with Hall, who had arranged for a private jet to fly him in from Atlanta to watch the forensic imaging process.

The team stayed for nearly eight hours, capturing digital images of the highly restricted election management system and voting machines.

In a recorded March 2021 phone call that was entered as evidence in the Curling case, Hall said the team’s work was exhaustive.

“They scanned all the equipment, imaged all the hard drives and scanned every single ballot,” he said.

In the end, it wasn’t enough. No evidence of fraud was found.

Biden was sworn into office on Jan. 20, 2021.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.