The ‘defunding’ police debate and reimagining public safety: Kamala Harris’ record on a fraught American issue

- Share via

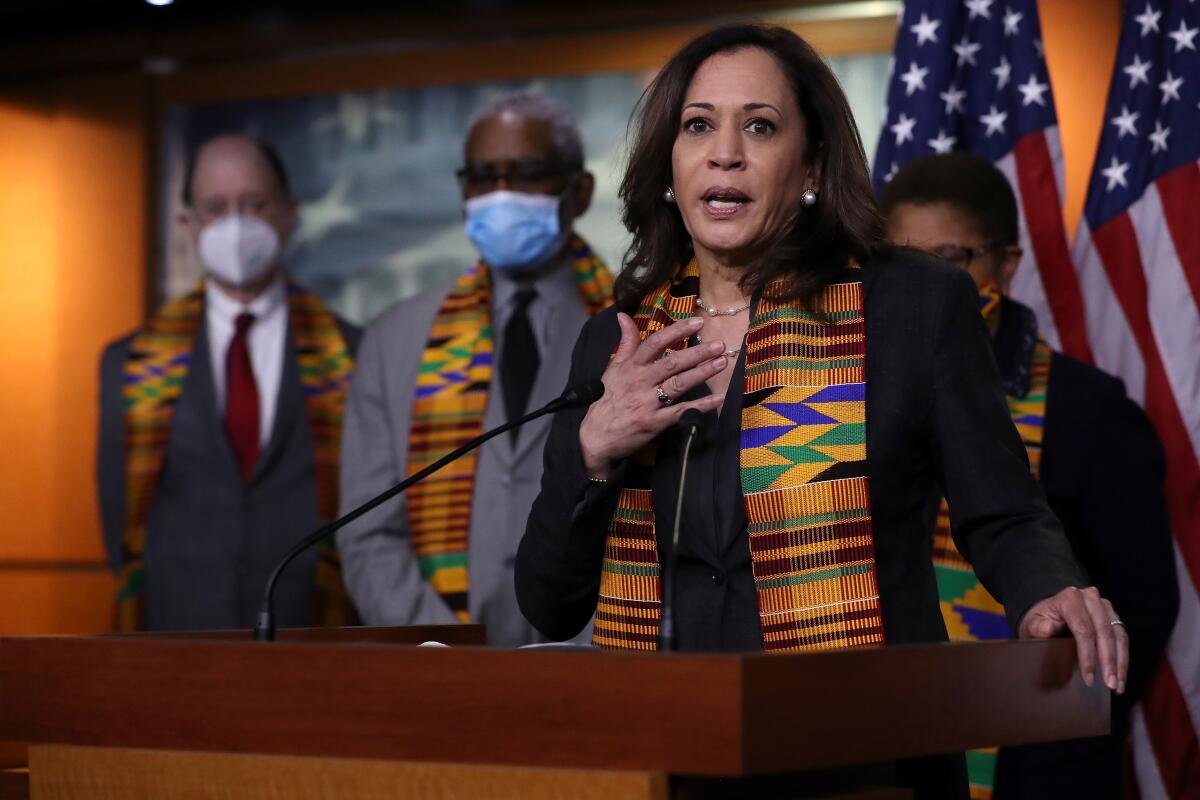

A few weeks into the largest racial justice protests in modern American history, the lone Black woman in the U.S. Senate appeared on “Good Morning America” to address one of the most controversial aspects of the debate.

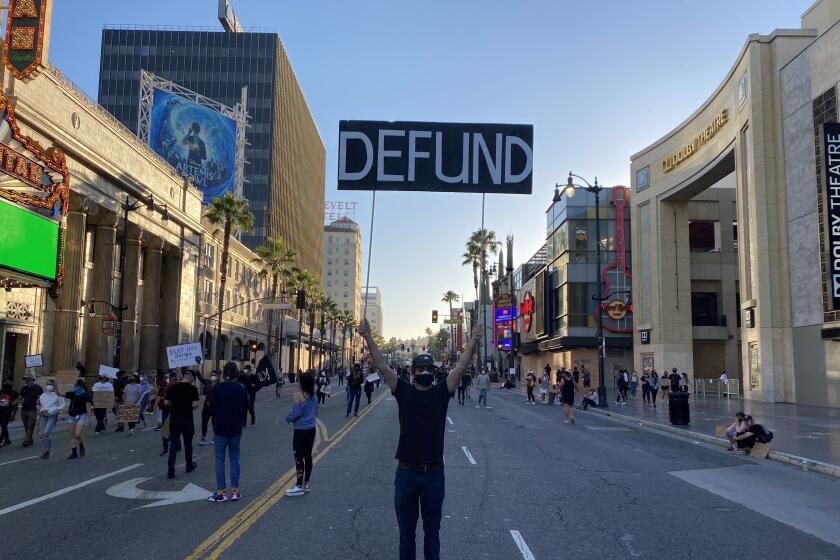

Massive crowds had taken to the streets nationwide to protest police killings of Black Americans, including George Floyd. Their demand that U.S. cities “defund police” and reallocate law enforcement funding to social programs was gaining traction. Then-President Trump had criticized the idea as a “radical” one from Democrats, and then-Sen. Kamala Harris — a former prosecutor who’d written a book titled “Smart on Crime” — was asked to respond.

Harris — who is now running against Trump for president — said in the June 2020 telecast that Trump was “creating fear where none is necessary.” She said the “status quo” belief that more police officers mean greater public safety is “just wrong,” and that what American communities needed was investment in public schools, better access to healthcare, more job opportunities and family incomes that last “through the end of the month.”

When ABC’s George Stephanopoulos asked if she supported a plan by then-Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti and the L.A. City Council to redirect $150 million in police funding to social programs, Harris said she applauded the move. When Stephanopoulos asked if the “bottom line” for her was “fewer police on the streets,” Harris again stressed investments rather than cuts.

“We need to recognize that if you invest in communities, they will be healthy, they will be strong, and we won’t have a need for the militarization of police,” she said. “That doesn’t mean we get rid of police. Of course not. But we have to be practical about this.”

The interview captured an important moment in America’s long fight for racial justice, when Americans were voicing collective outrage and police reform advocates sensed real change was possible after generations of failures.

It also captured a pivotal moment for Harris, who was about six months removed from her first failed presidential run and still a couple of months before being picked as then-candidate Joe Biden’s vice presidential running mate.

Harris seemed unfettered — perhaps emboldened by the palpable sense of history at work. She spoke extemporaneously and at length, in one interview after another, about a tremendously fraught political issue that had long felt personal to Black Americans but was nonetheless novel — if not threatening — to many others in mainstream America.

More than four years later, Harris is the nation’s most ascendant Black politician since Barack Obama, and her candor in 2020 is colliding with her ambition to lead a nation that has shifted decidedly to the right on issues of policing and public safety.

Trump is using her past remarks to cast her in simple terms as a dangerous proponent of “defunding police,” while her campaign is clamoring to remind voters of her prosecutor past and the Biden administration’s vast support for law enforcement through COVID-19 recovery aid, including to cities such as Los Angeles.

As with the “defund” debate more broadly, the rhetoric on both sides is oversimplified — and the reality much more nuanced.

Carrying the message

Activists in Los Angeles had been denouncing the Los Angeles Police Department’s multibillion-dollar budget for years, but the protests in the spring of 2020 were something different. Tens of thousands of people had marched, and city leaders knew they had to do something.

“It was a big deal. There was a lot of attention. There was a lot of public pressure. Folks were in the streets, and people got quickly organized behind this slogan of ‘defund the police,’” said Marqueece Harris-Dawson, a member of the Los Angeles City Council since 2015 and its incoming president.

Harris-Dawson said he remembers thinking that city leaders shouldn’t “govern by slogans,” but also that they were clearly “being called on to look at how we are spending our money” on police, and that it was “as good of an opportunity as any” to do just that.

He wasn’t alone.

Across the country, local leaders were grappling with whether their police budgets had become so lopsided that they were precluding more promising public safety initiatives — especially given that the onset of COVID-19 had sent many city revenues into a free fall.

It was against this backdrop that Harris gave the round of interviews about police budgets that are getting new scrutiny today — on “Good Morning America” and also MSNBC, “The View,” “Ebro in the Morning” on HOT 97 in New York and Power 106 with Nick Cannon in Los Angeles.

Harris largely avoided the “defund” slogan, but told Cannon that “we have to redirect the resources” being gobbled up by police departments. She said greater investments in education and jobs were critical, and repeatedly drew a contrast between poor, under-resourced city neighborhoods being unsafe despite being heavily policed, and richer, well-resourced suburbs being safe despite far fewer patrols.

“This is no coincidence,” she said.

Vice President Kamala Harris is promising to work to eliminate federal taxes on tips paid to restaurant and other service industry employees

In one interview after another, Harris noted that American cities routinely spend a third of their budgets on police while falling far short of the necessary investments in other areas, such as education.

“This whole movement is about rightly saying we need to take a look at these budgets and figure out whether it reflects the right priorities,” she said on “Ebro in the Morning.” “When today in America, two-thirds of our public school teachers are coming out of their own back pocket to help pay for school supplies, when we have for generations now been defunding public schools but yet militarizing police departments, we need to have this conversation and critically examine and understand this is not working. It’s not working.”

On “The View,” Harris said that “a big part” of the conversation was “reimagining how we do public safety in America.”

Melina Abdullah helped organize many of the 2020 protests in L.A. as a leader with Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles. The Cal State Los Angeles professor is also now the vice presidential running mate of academic, activist and independent presidential candidate Cornel West.

Abdullah said activists had already forced the concept of defunding police into the mainstream by the time Harris did her round of interviews, and that Harris did little other than try to explain the idea to the American public.

“We never saw evidence of her actually diverting funds,” Abdullah said, “which would have been the hope.”

The message shifts

Within months, Harris was Biden’s running mate and distancing herself from the “defund” concept in no uncertain terms.

“Joe Biden and Kamala Harris do not support defunding the police, and it is a lie to suggest otherwise,” Harris’ then-press secretary said in October 2020.

The shift showed Harris getting in line with Biden’s stance, but also reflected a rapidly changing political landscape. The COVID-19 pandemic was helping to usher in a surge in violent crime, and the American public was sliding back toward the political center on police and public safety.

A Gallup poll just weeks after Harris did her round of interviews found that 47% of Americans — and 70% of Black Americans — supported reducing police budgets and shifting funding to social programs. By May 2022, a similar Gallup poll found only 35% of Americans, and half of Black Americans, felt that way.

In Los Angeles, the City Council’s $150-million cut to the LAPD’s budget became mired in politics, with the funds fought over and used in part to pay off city debt rather than fund new social programs. Police officials said the cut forced them to reduce their ranks, but it did not lead to long-term spending reductions.

In fact, the LAPD’s budget has only increased, in part to pay for substantial raises for officers as the city has battled poor recruitment and retention. More than a quarter of the city’s budget — billions of dollars — remains allocated to the LAPD.

The LAPD is a changed organization a year after the social justice protests but hardly in the ways its critics wanted. Its budget was cut by $150 million last year, then increased by 3% this year. Still, the protests have forced major changes within the department, its daily operations and the way city officials see its role in public safety.

Nonetheless, the activists behind the defund debate had a major impact, said Mike Bonin, a progressive former City Council member who teaches public safety policy. They inspired Los Angeles County voters to pass Measure J, which required 10% of locally generated, unrestricted county funds to be spent on social services and not law enforcement or jails, and city leaders to reduce LAPD involvement in traffic incidents and in situations in which people are suffering from mental illness or homelessness.

Bonin said it took time for officials to learn what Harris had been stressing — that talking about cutting police funds was less effective than discussing investments in more novel public safety solutions.

“That’s the conversation I think Kamala Harris was trying to have [in 2020], and I suspect it’s the same conversation she is trying to have now,” Bonin said. “It’s responsible government.”

The message today

Harris and Trump hold very different positions on American policing.

Harris has supported federal oversight of troubled police agencies, stressed the need to hold bad officers accountable, and rejected the arming of police agencies with military equipment. She has praised major reforms such as the introduction of body cameras — including under her watch in California — and credited Black Lives Matter with instigating those improvements.

She says she supports — and supports funding — good, modern, constitutional policing.

Trump has suggested police need to be more aggressive, has cast doubt on federal monitoring of local departments, and has said he would supply police agencies with fresh military equipment. He has ridiculed racial justice protesters while promising to pardon the Jan. 6 insurrectionists who stormed the U.S. Capitol on his behalf — many of whom assaulted police officers.

He has said he would fund police to go after criminals and immigrants who are in the country without authorization in new, proactive ways, including through old strategies such as “stop and frisk.”

President Trump has a hard-line position on policing. Joe Biden urges reforms to limit the use of force but rejects calls to ‘defund’ the police.

Both candidates have tried to distance themselves from the idea of “defunding” police — and to tie their opponent to it.

At a recent campaign event with Michigan law enforcement officials, Trump accused Harris of being a longtime proponent of the idea, and of wanting to “destroy policemen in general.”

“She’s always been for defunding,” Trump said. “If she ever had a chance she would do whatever she could to defund the police, because that’s where her spirit is, that’s where her heart is.”

In a statement to The Times, the Harris campaign again denied that she ever supported “defunding” police. Harris campaign spokesman James Singer instead pointed to Trump’s criminal record — he is accused of breaking an array of election, tax and national security laws and was convicted of 34 felonies in a New York hush money case — and his suggestion in 2023 that Congress should “defund the DOJ and FBI” for their role in investigating him.

“The only candidate running for president who has ever advocated for defunding the police or proposed cutting funding for law enforcement is convicted felon Donald Trump,” Singer said.

For Abdullah, of BLM-LA, the Harris campaign’s position is not surprising. She said she views Harris as a “mixed bag” leader who has advocated for progressive criminal justice reforms in the past but is also clearly willing to shift her positions on such matters to get ahead politically.

Abdullah said she just hopes Harris again reconsiders “defunding” if she wins.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.