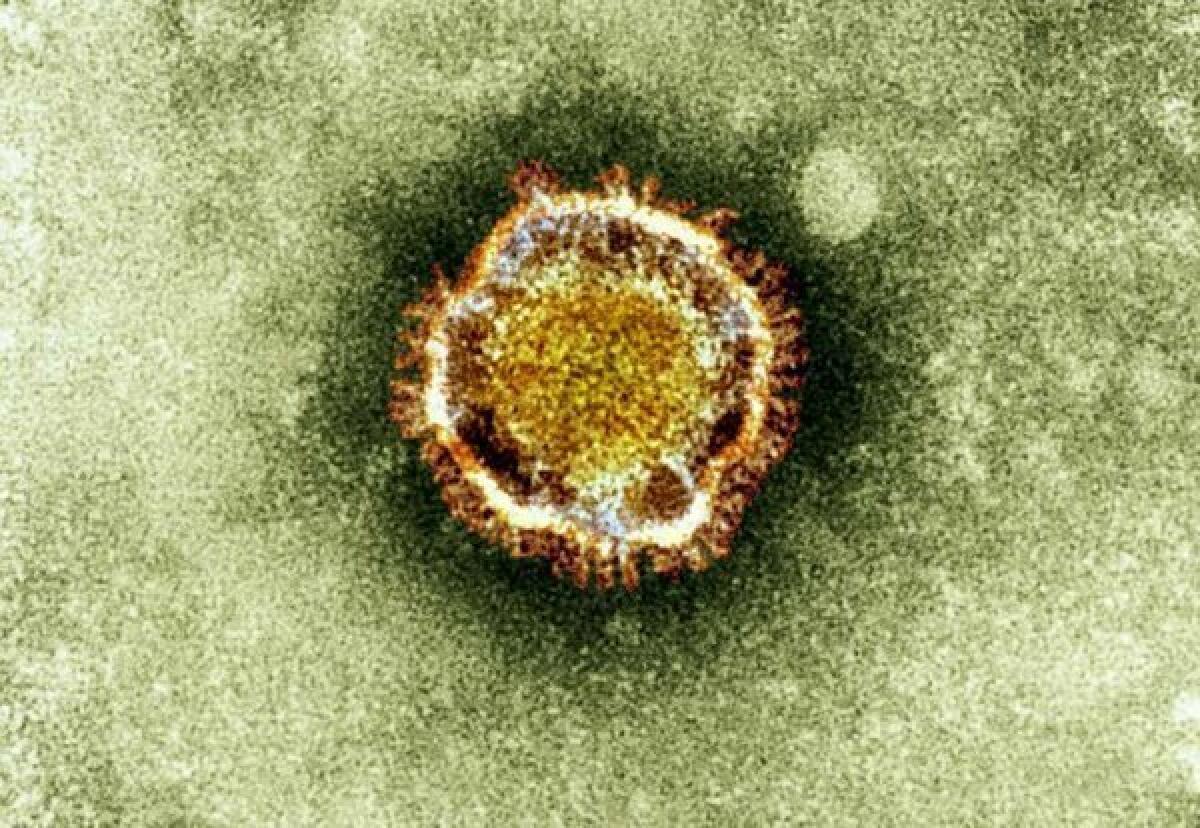

Scientists figure out how deadly coronavirus infects human cells

- Share via

Fifteen people have now been infected infected with the new strain of coronavirus that appears to have originated in the Middle East, and nine have died. The most recent casualty was a 39-year-old man in Saudi Arabia who became ill on Feb. 24, was admitted to a hospital on Feb. 28 and died two days later. So far, there are no known links between the man and anyone else who had the virus, according to the World Health Organization.

Scientists and public health officials have been scrambling to learn more about this coronavirus since its emergence last fall. Patients with the virus are overcome with severe lower respiratory infections, sometimes leading to multi-organ failure. Though the virus hasn’t sicked many people, the fact that it has killed 60% of its known hosts has people understandably worried.

An important piece of the puzzle was revealed Wednesday in the journal Nature. An international team of researchers identified the specific receptor that allows the virus to latch onto and infect human cells. The protein the virus targets is called dipeptidyl peptidase 4, or DPP4.

The DPP4 protein in humans is very similar to the versions in wild and domesticated animals, which probably explains why the new coronavirus can also infect cells from pigs, monkeys and bats. Indeed, one theory is that humans got the virus from bats, since it’s genetically very similar to three of the 60 known strains of bat coronaviruses. It’s also possible that bats gave it to another animal, which then gave it to humans.

Knowing that DPP4 plays a key role in infections should help researchers develop a vaccine, according to another report in Nature. It may also help scientists understand how the virus makes people sick. It could even make it easier for them to breed animals that can serve as stand-ins for people in laboratory experiments.

Return to the Science Now blog.

Follow me on Twitter @LATkarenkaplan