To steer her child away from obesity, a mother turns her life upside down

- Share via

Irie Mazas’ hands hovered over the boxes of bright red strawberries at the Adams & Vermont Farmers Market in Los Angeles.

“Mami!” the 7-year-old called to Miriam Bautista, who was several steps behind.

“How much?” Bautista asked the stall vendor in Spanish. Before the strawberries made it into a shopping bag, Irie was chomping on one, juice dripping onto her shirt.

Her mother frowned at the stain. Then she smiled.

A few months ago, Bautista worried she’d never get her daughter to eat healthful food. Noticeably overweight since about age 4, Irie would devour salty snacks, fast food and candy but cry if her mom put so much as a carrot on her dinner plate.

Bautista had shrugged it off. Her Mexican relatives proclaimed the tubbiness made her daughter even cuter. Then Bautista was diagnosed with gestational diabetes while pregnant with her second child. It dawned on her that the family’s food choices were hurting not just her own health, but Irie’s as well.

“That’s when I started to read labels, to be more aware of what I buy,” she said. “I realized that everything I was eating was harmful. I said, ‘My daughter needs to learn this too.’”

Bautista’s struggles with her daughter’s weight are hardly unique. Early childhood obesity is one of the most intractable health issues facing Los Angeles County, where about 20% of 3- and 4-year-olds are obese. Among school-age children, 45% are overweight or obese by the time they reach fifth grade — higher than the percentage of Californians as a whole.

Obesity is particularly acute among young Latinos, a fact that alarms health officials because more than half of the babies born in Los Angeles County are Latino. Almost a quarter of 4-year-old Latino children in the county are obese, compared with 17% of whites, 15% of blacks, and 11% of Asians, according to federal data.

The health consequences grow with age. Dr. Juan Espinoza, a pediatrician at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles, said he regularly treats obese kids in elementary and middle school with “50-year-old man” problems such as fatty liver disease, hypertension, Type 2 diabetes and joint pain.

“Most of those kids have been overweight for a long time,” Espinoza said. Obese children are likely to remain obese as adults, increasing their risk of heart attack, stroke, cancer and premature death.

Their offspring are also more likely to be obese, studies show. One of the biggest risk factors for childhood obesity is a mother’s body mass index before she becomes pregnant.

“Bigger adults are going to have bigger kids,” said Michael Goran, director of the Program for Diabetes and Obesity at CHLA. “This is becoming a generational issue.”

Seeking help

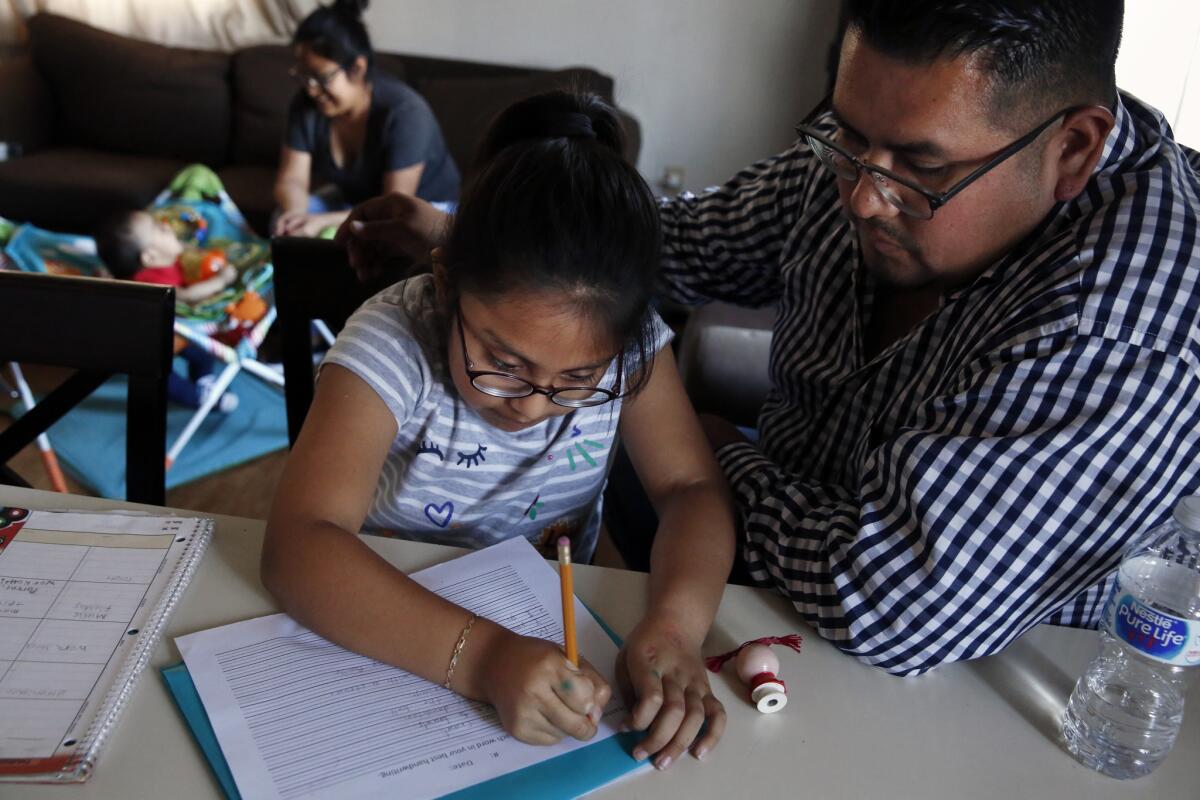

Bautista knew she’d be fighting an uphill battle to improve Irie’s eating. Extra pounds are the norm in her husband’s family, and Irie’s grandparents loved spoiling her daughter with pastries and other treats.

After several attempts to make Irie eat vegetables ended in tantrums, Bautista sought help from the girl’s pediatrician. The doctor referred them to a seven-week obesity prevention program called BodyWorks. Run by CHLA and AltaMed, an outpatient care provider, BodyWorks uses games, exercise, videos and healthful snacks to steer kids toward a better path.

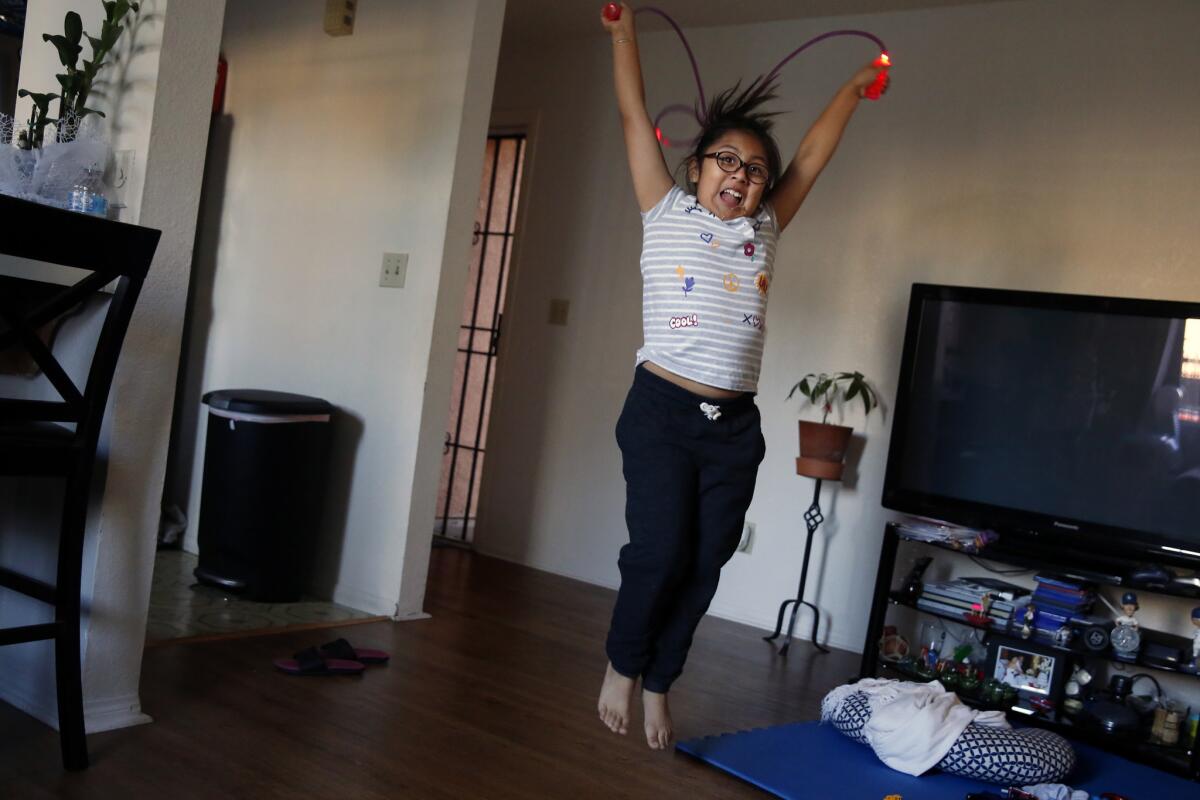

Irie began to come around. She tried vegetables for the first time: lettuce, then broccoli, then carrots. She learned that her plate should look like a rainbow, and about the vitamins and minerals she needs to grow.

Bautista learned about setting limits: no snacking before meal times, no eating fast food multiple times a week. She now offers Irie a healthful snack before leaving the house and brings along nuts and water so her daughter doesn’t beg for junk food. She has the kids stay home with her husband when she goes to the supermarket so she doesn’t have to contend with demands for chips, cookies and candy. And they walk to the farmers market each week instead of taking the car.

With her husband’s support, Bautista stood up to her in-laws, urging them not to give Irie unhealthful treats. Irie’s grandmother pushed back at first, Bautista said, but has complied with the request.

On a recent checkup six weeks into the BodyWorks program, Irie was no longer overweight, Bautista said.

“It makes me feel good to see these changes,” she said.

Irie is happy too. She recounted with pride how she eats one helping of fruit and one of vegetables at every meal. Broccoli, which she first thought “tasted weird,” is now her favorite vegetable, she said.

Prevention efforts

BodyWorks is just one of numerous initiatives aimed at breaking the cycle of early childhood obesity in Los Angeles. Other efforts have included free family nutrition classes at community health clinics; an anti-obesity campaign run by the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health that offered workshops and grocery store tours; a state law that sets milk and water as the default options for kids’ restaurant meals; and bans on selling soda in public schools.

Yet experts are frustrated that childhood obesity rates remain so unacceptably high.

“Unfortunately, we are still at obesity levels comparable to peak rates in 2009,” said Shannon Whaley, director of research and evaluation at the largest of the county’s seven agencies that administer the federal nutrition program for Women, Infants and Children.

And things could soon get worse, experts say. Families are dropping out of programs like WIC for fear that their information will be shared with immigration enforcement officials or will undermine their efforts to attain legal residency. Last fall, the Department of Homeland Security said it was considering a policy change that would deny permanent residency to immigrants who used government benefits such as WIC or Medi-Cal.

Joy Ahrens, director of WIC for Northeast Valley Health Corp. in San Fernando, said patients have been asking to be dropped from the program, or they are not showing up to their appointments.

“We’re trying to tell them it’s in the best interest of your child and of your pregnancy,” she said. “But there’s definitely a lot of fear out there.”

A disease of poverty

Poverty also contributes to obesity, pummeling families from multiple angles.

Single moms working multiple jobs have little time to breastfeed or pump breast milk, cook healthful meals, or ensure their kids get enough exercise. Parents with little money are less likely to live near supermarkets, pushing them to shop at marts and liquor stores stocked with processed, calorie-dense foods. Even when fresh groceries are available, parents may have no way to prepare them.

“I have patients who live in garages, or live in places where they don't have access to a kitchen. Sometimes they don’t have access to refrigeration,” said Dr. Gina Johnson, pediatric medical director for Northeast Valley Health Corp., which operates 14 clinics that primarily serve low-income Latino families.

The questions parents ask are revealing: Is it OK to sweeten milk with chocolate powder? Can I really only give my child one cup of cereal for breakfast?

“For this population, just having enough to eat is what they’re most worried about,” said Victor Solano, a health educator at a clinic in San Fernando. “So they focus on quantity of the food, not so much quality.”

It’s not surprising, then, that kids in Los Angeles County’s lowest-income neighborhoods are far more likely to be obese than kids in wealthy communities, research shows.

“If you look at Malibu or Beverly Hills, the prevalence of childhood obesity is 5% or under,” Goran said. “But if you look at East L.A. or South L.A., it can be 30% or 35%.”

Estelita Sebastian, a single mother in MacArthur Park who works part time as a housekeeper, started buying fast food for her 11- and 5-year-old sons after they became too old to qualify for WIC. She doesn’t own a car, so stopping for food on the way to and from school seemed more convenient than walking 15 minutes to her local Smart & Final and carrying groceries home, she said.

Last summer, a doctor informed Sebastian that her children were overweight and that her oldest, Gustavo, had hyperglycemia and high cholesterol. She and her sons enrolled in BodyWorks, collectively lost several pounds and are no longer overweight. Through trial and error, she realized she could save money by cutting out junk food and cooking at home. But she’s had to condense her work schedule and stay up an hour later every night to get everything done.

“It was hard,” Sebastian said. But Gustavo’s diagnosis gave her the strength to persevere. “I felt guilty and I thought, ‘No, this has to change.’”

Some progress

At the Bautista household, meals are very different than they were six months ago. The family eats fewer tortillas, chips and pastries, and more fruits, vegetables and sugar-free foods. Chocolate milk has been replaced with low-fat plain milk. Portions are carefully measured, filling only the center of each plate rather than the entire dish.

Instead of making all treats off-limits, Bautista strikes deals. Irie can eat pizza, but only one slice that must be accompanied by fruit. She can have an ice cream, but only if she walks with her mom to the store and back.

CHLA is still evaluating the long-term effects of the BodyWorks program, but experts believe education initiatives like it will help push the needle on childhood obesity.

They have limited evidence to back them up. Between 2013 and 2016, the county’s public health department and its nonprofit partners trained 6,000 preschool and day-care providers on obesity prevention and worked with community agencies to provide educational workshops for parents of children ages 2 to 5. Follow-up surveys showed a 13% to 37% increase in parents’ understanding of proper nutrition and tactics for encouraging children to eat better. (The county has continued to support some of these efforts under a $15-million-a-year program called Champions for Change.)

Jaimie Davis, an obesity researcher at the University of Texas at Austin who worked in Los Angeles for many years, said many obesity-prevention strategies show promise, but they need to be coordinated and funded on a larger scale.

“It’s not a systematic approach,” she said.

Espinoza at CHLA said there’s a particular need for initiatives aimed at the youngest children. “This is a disease that, if addressed appropriately early on, can be prevented from impacting people’s lives long term,” he said.

The way Bautista sees it, change needs to start with parents taking childhood obesity seriously, educating themselves about nutrition and controlling what their kids eat.

“It’s not so people’s kids can be thin; it’s so they can be healthy,” she said. “We’re going to do this, even if the kids don’t want to, because they’re not in charge. We’re in charge.”

Claudia Boyd-Barrett writes for the Center for Health Reporting at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at USC. Reporting was supported by a grant from First 5 LA.